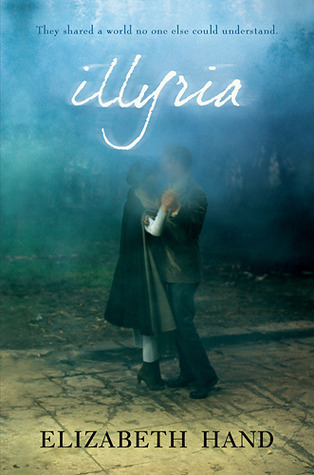

Elizabeth Hand’s new novel Illyria follows in a long tradition of science fiction and fantasy stories which reference the works of Shakespeare, particularly the romances, and Hand’s lyrical writing style is a wonderful fit for the dark romance she sets out to tell. The romance tells of the relationship between two cousins, Maddy and Rogan, but like that of the twins Viola and Sebastian in “Twelfth Night” to which the title Illyria alludes, the relationship between Maddy and Rogan proves to be a powerful touchstone for drawing together all the “big ideas” of love, ambition, and conformity to family and social expectations.

Elizabeth Hand’s new novel Illyria follows in a long tradition of science fiction and fantasy stories which reference the works of Shakespeare, particularly the romances, and Hand’s lyrical writing style is a wonderful fit for the dark romance she sets out to tell. The romance tells of the relationship between two cousins, Maddy and Rogan, but like that of the twins Viola and Sebastian in “Twelfth Night” to which the title Illyria alludes, the relationship between Maddy and Rogan proves to be a powerful touchstone for drawing together all the “big ideas” of love, ambition, and conformity to family and social expectations.

Maddy, the protagonist, and her cousin, Rogan, are teenagers growing up in the suburbs of Yonkers in the 1970s. The cousins were born on the same day, Maddy in the morning and Rogan at night, and so they think of themselves as twins, inseparable opposites.

So Rogan was darkness, I was light, and over the years the metaphor was extended to include just about every doomy literary reference you can imagine-Caliban and Ariel, Peter Pan and Wendy, Heathcliff and Cathy, Abelard and Heloise, Tristan and Iseult, Evnissyen and Nissyen . . . .

The cousins seem intent upon invoking the doom dictated by their literary references for, though cousins, they experience first love with one another. The proximity of the many houses filled with their endless spying relatives, the unrelenting disapproving gaze of the family, and Maddy’s own belief that Rogan is her dark twin all lend themselves to the feeling that the cousins are moving toward some violent end. Even Rogan’s pet name for Maddy, “mad girl,” seems to indicate that it is the self-destructive streak within each of them to which the other is drawn.

It was like my own reflection in a black mirror, only a mirror that stripped the flesh from my skull so that what grinned back was not the self I showed the daytime world, not the girl who woke and walked and struggled and laughed but the terrible me, the true me; the mad girl inside Maddy.

Maddy and Rogan’s frustrated desires are to some extent their family inheritance from their paternal great-grandmother Madeline. Though Madeline had been a successful actress at the turn of the twentieth century, upon her marriage she had retired from the stage, and, in her desire to maintain her own power and fame within the hierarchy of the family, actively discouraged her own children and grandchildren from following in her footsteps for fear that their own success would outstrip hers. By the time of Maddy and Rogan’s generation, the family is one from which, through verbal abuse and physical bullying, all creativity and artistic ambition has been brutally weeded out. Thus the tragedy of Maddy and Rogan’s forbidden desire for one another is in many ways a reflection of their frustrated desires for a life of passionate self-expression, artistic as well as emotional.

Into the parched landscape of Maddy and Rogan’s lives comes a new teacher who proposes to put on a Shakespeare play. Originally, Maddy suggests that she and Rogan participate in the play as a way for them to be together despite their parents’s prohibitions. The play, however, proves to be the spark that falls into the dry kindling of their emotionally and aesthetically barren lives, and the rest of the story moves inevitably toward the firestorm which will burn down the secret world, their own private Illyria, which they have managed to build together.

As in her previous novel Mortal Love, Hand does not distinguish romantic obsession from artistic obsession, and the many references to twins and reflections further complicates ideas regarding the source of inspiration and the expression of desire. References to other Shakespeare-based works by W. H. Auden and Charles and Mary Lamb create additional gothic overtones of fantasy worlds and magic, shadow selves and madness, though the reader does not need to be familiar with these other works in order to enjoy the complex nuances which Hand deftly weaves into her story. As always, Hand is a genius at portraying the life of the senses, touch, smell and sound as well as vision, and her images are so vivid that they are felt like molten sparks falling upon one’s skin.

Ultimately, Elizabeth Hand demonstrates in Illyria what draws so many of us to the literature of the fantastic, and what connects it so strongly to Shakespeare: the fact that fantastic worlds — no matter how strange they appear in regard to place, time, or culture — throw into contrast what we find most recognizable, that experience we call “being human.”

(PS Publishing, 2007)