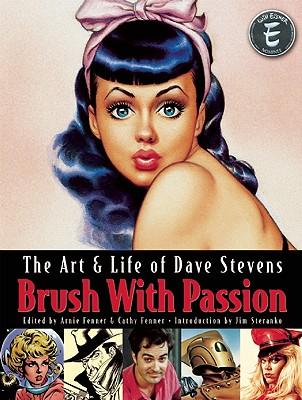

Brush With Passion: The Art and Life of Dave Stevens is an utterly gorgeous book. It’s also a terribly sad one. This is not just due to the Stevens’ untimely passing from hairy cell leukemia, nor is it entirely derived from the shoulda-woulda-coulda success of The Rocketeer. Instead, it comes from the reader’s dawning realization that Stevens’ autobiographical notes are the ongoing narrative of a man continually defining himself by what he’s not — not a comics artist, not the guy who’s going to make a million doing The Rocketeer, not the guy who’s going to replace Vargas doing pinups for Playboy, not this, not that. It’s not until the very end of his life that Stevens seemingly figured out what he was, or more importantly, what he could be, and the fact that this was never given time to blossom is perhaps the saddest thing of all.

Brush With Passion: The Art and Life of Dave Stevens is an utterly gorgeous book. It’s also a terribly sad one. This is not just due to the Stevens’ untimely passing from hairy cell leukemia, nor is it entirely derived from the shoulda-woulda-coulda success of The Rocketeer. Instead, it comes from the reader’s dawning realization that Stevens’ autobiographical notes are the ongoing narrative of a man continually defining himself by what he’s not — not a comics artist, not the guy who’s going to make a million doing The Rocketeer, not the guy who’s going to replace Vargas doing pinups for Playboy, not this, not that. It’s not until the very end of his life that Stevens seemingly figured out what he was, or more importantly, what he could be, and the fact that this was never given time to blossom is perhaps the saddest thing of all.

But if there is sadness here, there is also beauty and joy. The joy comes from many places: the shared reminiscences of friends and peers like Jim Steranko and Arnie & Cathy Fenner; the pleasure that Stevens clearly took in sharing his influences and history with his audience, the unabashedly good deeds he did in helping out his muse Bettie Page, and more. This book is, after all, a celebration of the man’s life as well as his art, and a celebration it is. One gets the sense, reading anecdote after fondly remembered anecdote, of the sheer love that these wildly disparate people all had for Stevens. Peers, employers, friends, lovers — they all give testimony as to the depth to which Stevens enriched their lives. The last of these, an epilogue by the artist William Stout, is a graceful, hopeful remembrance that brings the story full circle, and which may just invoke a sniffle or two.

That leaves the beauty, and there is beauty here a-plenty. The book is eooxceedingly lavishly illustrated. This is an illustrated life, after all, and the Fenners don’t skimp. Everything necessary to telling the story is here, gorgeously reproduced and given detailed captions for explanation. Childhood iconography and family photos are included; so are pencil sketches, full color reproductions, movie storyboards, reference, and more. The end result is a book that is stuffed — but not overstuffed — with everything visually pertinent to Dave Stevens’ career, both from his work and the world around him that provided his inspiration.

It is, of course, the Stevens work that most readers will be eager to see, and that does not disappoint. Those who just know Stevens as “the guy who drew The Rocketeer” are in for a bit of a shock, as the full range of his work is on display here. That includes his non-PC homages, his Tarzan and Rocketeer work, the studies for the never-realized Mimi Rodin project, and most of all, the pinup art. There’s lots and lots of it here, which is to say that anyone who opens the book and isn’t prepared for an armada of magnificently rendered nude or semi-nude women is going to have a hard time getting past about chapter 8.

The art itself is brilliant, unmistakably Stevens even when he was doing homage or rough pencil sketch. I’m no art critic, but even I can see the absolute vibrancy of the material, the energy that comes through in every image.

It’s clear that Brush With Passion is a labor of love, a lovingly assembled remembrance of a career that provided a great deal of memorable work. How fortunate we are, then, that Dave Stevens had such friends as these who were willing to produce a work like this; how even more fortunate that he was generous enough of spirit to set down his creative journey without excuses or lacunae. For both the sadness and the joy it contains, this book is a treasure of a kind, and well worth the time of anyone with even a passing interest in Stevens’ life and work.

(Underwood Books, 2008)