I’ve long followed Charles de Lint’s writing, starting with, if I remember correctly, Moonheart way back when, and I’ve been as close as I ever come to being a fan for years. (I even got my hands on some early stories, somehow.) So when I was asked to do a review of The Cats of Tanglewood Forest, I said, “Yes. I haven’t had a chance to read de Lint in a while.”

I’ve long followed Charles de Lint’s writing, starting with, if I remember correctly, Moonheart way back when, and I’ve been as close as I ever come to being a fan for years. (I even got my hands on some early stories, somehow.) So when I was asked to do a review of The Cats of Tanglewood Forest, I said, “Yes. I haven’t had a chance to read de Lint in a while.”

Lillian Kindred lives with her Aunt on a remote farm at the edge of a forest – Tanglewood Forest, to be exact. Lillian is what we could call, for lack of a better word, a “tomboy” – that’s not really an exact fit, but it takes into account the fact that she spends as much time roaming the forest (hunting fairies, as it happens – not for any dark purpose, but just to watch them) as doing chores, looks with horror at the idea of wearing a dress, and in general is not at all what we’d call “girly.” Being a generous soul, Lillian is in the habit of bringing little gifts on her forays into the woods – specifically, food – and so has become friends with the cats, especially, which seem to live in the forest in large numbers. (Anyone who knows cats knows that food is a sure bet to winning their affections.)

Then one day, while Lillian is exploring the forest, she happens upon an ancient beech and decides to take a nap at its base. She awakes to a sharp pain in her leg and the realization that she’s been bitten by a snake. As she starts to feel the effects of the venom, the cats come to her rescue, gathering around her. She passes out, and then wakes later as a kitten. At least, that what anyone else sees. When Lillian looks at her reflection in a pond, she sees a girl. She finally, on the advice of Annabelle, her aunt’s cow, makes her way to Old Mother ‘Possum, who has very strong magic. En route, she makes the acquaintance of T. H. Reynolds, a fox. Mother ‘Possum finally agrees to do what she can, but warns Lillian that there will be consequences – there are always consequences. Nevertheless, Lillian insists on becoming a girl again. When she wakes this time, she is, indeed, returned to her former self, but she soon learns that the consequences are worse than she imagined.

And now Lillian has to try to set things right.

The story is really an odyssey, as Lillian seeks help from her friends on the rez, who take her to Aunt Nancy (of whom everyone is terrified), who sends her to the Bear People, and ultimately, the fearsome Father of Cats. As such, it falls into discrete episodes linked by the overarching goal – to return to the status quo ante.

The narrative is straightforward in a way that’s somewhat unusual for de Lint. I chalk it up to the fact that it’s really a children’s story, although somewhat longer than we might think of for children. (Although thinking back to my childhood, I was reading books this long in grade school.) There’s also an element that ties into this, something that I’ve noticed in others of de Lint’s writings for younger readers: there’s a certain distance to the narration, a lack of immediacy, that serves to keep the reader somewhat outside the story.

Perhaps this distance is due to the way de Lint has interwoven dreams and reality. Lillian is sure that T. H. Reynolds, for example, is from her dream of being a kitten – except that when she was a kitten, it was all very real, the way dreams are. It leads to more than one “Huh?” moment, as Lillian tries to disentangle reality from her imagination. Add in the complicating factor of traveling back and forth through time – because that’s what Lillian is doing — and the story becomes very complex indeed.

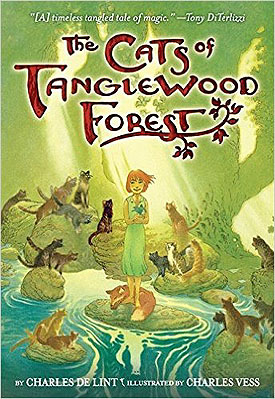

Charles Vess’ illustrations for this story are perfect. They often share pages with text and bring a new element to the narrative. Atmospheric and decorative, they also come very close to being part of the story, almost entering into the area of the graphic novel.

On the whole, this is one I’d have no hesitation in recommending to younger readers, say just shy of middle-school age.

(Little, Brown and Company, 2013)