And Here My Troubles Began is the second volume of Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning depiction of his father’s experiences in the Holocaust in graphic novel form. It is the culmination of the story that began in Vol. I, subtitled My Father Bleeds History, which covered Vladek Spiegelman’s life from the early 1930s through the growth of the Nazis’ power, increasing persecution of the Jews, and finally his own arrival at Auschwitz.

And Here My Troubles Began is the second volume of Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning depiction of his father’s experiences in the Holocaust in graphic novel form. It is the culmination of the story that began in Vol. I, subtitled My Father Bleeds History, which covered Vladek Spiegelman’s life from the early 1930s through the growth of the Nazis’ power, increasing persecution of the Jews, and finally his own arrival at Auschwitz.

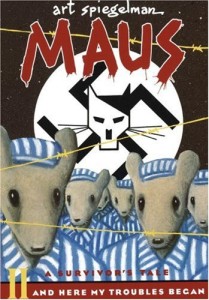

Maus depicts the Jews as mice, bullied, beaten and murdered by German cats. Poles are depicted as pigs, French as frogs, Americans as dogs. The characters of each “race” all look substantially the same, differentiated only by their clothing; and the Jews often succeed at disguising themselves by wearing masks, particularly pig masks.

The books combine two stories, Vladek’s in the past and Art’s in the present as he attempts to learn his father’s story and turn it into a “comic.” Both become more harrowing in Vol. II. In fact, its supremely ironic and understated subtitle, And Here My Troubles Began could apply to Art’s tale as well as his father’s — in a different way and degree, of course. But the artist’s struggle to extract the story from his irascible old man and the trauma that Vladek puts his family through daily both parallel his own story of his struggle to survive in the camp.

These days we would look at Vladek Spiegelman and say, here is a man with post-traumatic stress. His family doesn’t have the comfort of a label to put on him. They only know that he is nearly impossible to live with: manipulative, stingy, miserly, and alternately tender and cruel. His son the graphic novelist demonstrates convincingly that suffering hasn’t made his father noble. At one point, Art picks up an African American hitchhiker, whom his father refers to as a “schwarzer,” and toward whom he reveals blatantly racist attitudes.

Vladek emerged from his experiences as a very resourceful man, and one who didn’t usually examine his methods. An episode in Auschwitz in which he uses his influence with a Polish kapo to get shoes and a belt for an old man he knew on the outside is followed by an episode in the present day, in which he sneaks from his cheap summer cabin into a neighboring resort where he can enjoy the amenities — bingo, the pool, movies — and share them with his family. His son in the books only hints at and doesn’t dwell much on the between-the-lines information about how his father emerged as a survivor. Vladek says he was lucky, but from the parts of the story that we’re told it is apparent that he was always ready to seize anything that would give him an advantage. He learns shoe repair so he can fix the Nazis’ boots and is often paid in food; telling how he sometimes shared them with the Polish kapo, he says to Art, “If you want to live, it’s good to be friendly!” He doesn’t ever portray himself as engaging in any morally questionable behavior, but the question is always there in the background.

And Art himself often comes off as less than sterling, badgering his father for his story even as his father’s health is failing, panicking when it seems his father might want to move in with him and his wife, and frequently snapping at him when he acts bizarrely. It’s an accurate picture of a confused family dealing with lingering mental health issues that it doesn’t understand.

The most affecting part of Maus II for me was one in which Art and his father are going through the few photographs that survived the war. On one page in particular, the scene is made up of composite panels that complete the full picture of Vladek and Art on the couch, photos of dead relatives spread out on the floor at their feet. Nearly all are of his wife’s family, as he explains in the page’s final dialogue balloon: “So only my little brother, Pinek, came out from the war alive … from the rest of my family, it’s nothing left, not even a snapshot.”

Spiegelman turned that nothing into a lasting work of art.

(Pantheon, 1991)