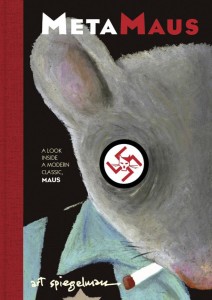

Art Spiegelman’s Maus was a monumental undertaking. I don’t mean because of how it changed the way the world looks at and thinks about Hitler’s genocide against the Jews of Europe, or the way the world looks at and thinks about comics as literature. Although it certainly did both. I mean just the physical act of creating his work, first published in two volumes in 1986 and 1991. So that the world – and particularly persons like me who are not artists or illustrators themselves – can understand just how he did what he did, and why, Spiegelman and Pantheon bring us MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus. Along the way, we get an inkling of the artistic, psychological and spiritual motivations that drove Spiegelman, motivations that even a quarter-century later the artist and author himself may be still teasing apart.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus was a monumental undertaking. I don’t mean because of how it changed the way the world looks at and thinks about Hitler’s genocide against the Jews of Europe, or the way the world looks at and thinks about comics as literature. Although it certainly did both. I mean just the physical act of creating his work, first published in two volumes in 1986 and 1991. So that the world – and particularly persons like me who are not artists or illustrators themselves – can understand just how he did what he did, and why, Spiegelman and Pantheon bring us MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus. Along the way, we get an inkling of the artistic, psychological and spiritual motivations that drove Spiegelman, motivations that even a quarter-century later the artist and author himself may be still teasing apart.

This 300-page hardcover book consists of transcripts from a series of interviews Spiegelman did with Hilary Chute, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of English at the University of Chicago. As Spiegelman writes in a preface:

She soon became my chief enabler and associate editor in a project I kept resisting. (It was hard to revisit Maus, the book that both “made” me and has haunted me ever since; hard to revisit the ghosts of my family, the death-stench of history, and my own past.) …”

In addition to the text of the interviews, the book has copious drawings, from the original Maus books as well as many of the original and intermediate sketches of those final drawings; photos and drawings that served as source material for many of the panels in the books; family photos, doodles and original drawings done for this book; and extensive examples of the works of other comics artists who were some of Spiegelman’s inspirations. There’s a lengthy section of a transcription of one of Art’s early interviews of his father, in which we see the man’s actual speech patterns, to compare with a section in which Art talks about how he had to edit that speech to fit comics panels without losing their authenticity. When Chute asks Spiegelman what his own family thinks about the books, he says, basically, “You’d have to ask them,” which leads into a section in which she interviews his wife, Francoise Mouly, and their daughter Nadja and son Dash.

As a major bonus, the book comes with a DVD titled “The Complete Maus Files.” It is a hyperlinked disc of the full Maus book in one volume as Spiegelman originally intended and an archive of audio interviews with his father, photos, notebooks, drawings, essays and more. On each page of the DVD version of the book are links that you can click to hear audio files of Vladek’s words that led to the images and text on the page, and comments by Art on that text and those images. In many cases you can also see the series of underlying drawings that preceded the finished page. And much more. I barely scratched the surface in preparing for this review.

But the core, for me, is the book itself. It isn’t for everybody. Not everybody likes to read the liner notes of music albums, or to read interviews of or essays by musicians, writers and artists in which they discuss their artistic process. If you do enjoy that sort of thing, and if you have read the Maus books and want to know more about them and their creator, you’ll love MetaMaus. I did.

I love to learn “meta” details such as that Spiegelman drew all of the two books in the exact size as depicted in the final product. Rather than drawing the panels larger and then shrinking them down to fit the size of the book’s pages, he drew them as they would appear in print, a much more difficult process.

The book has three main sections: Why The Holocaust? Why Mice? and Why Comics? Spiegelman says that those three questions are, in essence, what everybody has asked him since the first volume was published in 1986. As an aside, we learn why the book was published in two volumes, and a lot of other things about the publishing industry in the U.S. and around the world, and the way it reacted to Maus and its difficult subject matter and format.

Among the most fascinating matters to me was “Why Mice?” It’s impossible to go into all the facets of this complex aspect of the book in what’s supposed to be a short review. But it ranges from a comparison with ancient use of animals in a medieval Haggadah (the Passover story that is read at the holiday meal); to the depiction of Jews as vermin that began in the middle ages and culminated under Hitler; to the cute and fuzzy depiction of those same “vermin” by Disney and other American cartoonists and animators; to the psychological aspects of an artist taking refuge behind an animal mask.

Perhaps my favorite piece in MetaMaus is on page 73, in which Spiegelman seems to get at the real inner kernel of what Maus is about:

The story of Maus isn’t just the story of a son having problems with his father, and it’s not just the story of what a father lived through. It’s about a cartoonist trying to envision what his father went through. It’s about choices being made, of finding what one can tell, and what one can reveal, and what one can reveal beyond what one knows one is revealing. Those are the things that give real tensile strength to the work – putting the dead into little boxes.

I realize that everybody isn’t going to find MetaMaus as compelling as I did, and many who were moved by the original Maus won’t even be interested enough to pick it up. Speaking for myself, I have always found great satisfaction, even uplift, in reading or listening to the words of artists as they talk about their creative process. In many cases, even if I don’t like or understand someone’s art or music, I still love to hear them talk about what drove them to create it.

Maus isn’t about heroes. It’s about ordinary people who went through hell, and the effect that hell had on them and their children. MetaMaus to me is a more heroic tale. For grappeling with the intensely personal and at times devastating impact that history and family dynamics had on himself and then rigorously dissecting the artistic and personal choices he made over more than a decade in the creation of that original work, Art Spiegelman is a hero.

(Pantheon, 2011)