It’s a wise child that knows its own father — and wiser yet the father who knows his own child.

It’s a wise child that knows its own father — and wiser yet the father who knows his own child.

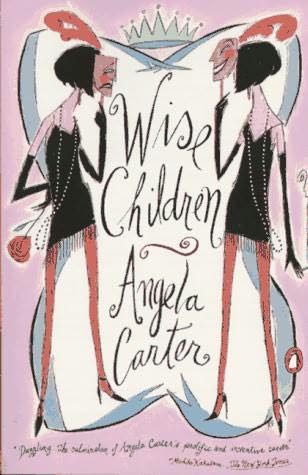

Carter’s novel draws its name from the quote above (the quote also appears as dialogue). The titular “wise children” are Dora and Leonora Chance, identical twin daughters of a man most foolish, the renowned Shakespearean actor Melchior Hazard. However, the world believes Nora and Dora to be the illegitimate children of Melchior’s twin, Peregrine, because Melchior refuses to acknowledge the girls as his. It’s Peregrine — a worldly traveler who lives up to his name — who utters the quote that provides the novel’s name, and who stands in admirably as the Chance twins’ father.

Wise Children, like Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, is comprised of stories within stories. The framing story concerns events occurring on the day of Melchior’s 100th birthday — which also happens to be Nora and Dora’s 75th birthday. But Dora runs away with the narrative and lays out a memoir for the “Lucky” Chances (as the sisters were known professionally), beginning two generations before they were even born, with their paternal grandparents. Along the way, readers are treated to a brief history of British live stage entertainment — with a brief foray into American movies — throughout the 1900s.

Dora is a very entertaining narrator, and the story she tells about her dysfunctional “family” is by turns affectionate, bawdy, and serious. She and her twin may never gain the acceptance they’d like from their true father, but that lack hardly slows them down personally or professionally (even if their triumphs are more vaudeville than high art). And they patch together a family of their own with their caretaker, her foundlings, and eventually Melchior’s first wife, who they take in and teasingly, but affectionately, refer to as Wheelchair (because she must use one to get around). Eventually, after wandering through Dora’s memories of the twins’ first 74 years, the narrative returns to the present, wrapping up with a birthday party for the ages.

It’s impossible to read Wise Children without taking note of the sheer, improbable number of twins romping among the pages. Besides Dora and Nora, Melchior and Peregrine, there are three other sets: Imogen and Saskia (Melchior’s by his first wife), Tristram and Gareth (Melchior’s by his third wife) and an unnamed pair of twins, a boy and a girl, who are Gareth’s (but given to Nora to raise). That a family could produce so many sets of twins seems impossible, and helps to underscore the larger-than-life tale that Dora tells us.

It’s also impossible to escape the Bard. Not only has the Hazard family made a living on stage performing in Shakespeare’s plays — Hamlet, MacBeth — even Nora and Dora join their father and their sisters in a movie production of A Midsummer’s Night Dream. There’s also Carter’s use of the twins — there’s one clear case of mistaken identity (Dora disguising herself as Nora so she can trick the latter’s beau into deflowering her), and the paternity of nearly every set of twins is in doubt. Not to mention that the Chances live on Bard Street.

As to be expected of any Angela Carter novel, there are many layers, references and nuances in Wise Children that bear further study. But even taken just as pure entertainment, Wise Children is a marvelous novel, immersing readers in Dora’s memories and entangling them in the personal and professional triumphs and nadirs of the extended Fortune family.

(Farrar Straus Giroux, 1991)