The Waterson:Carthy extended family is often described as the “First Family of English folk music,” sometimes even as the “Royal Family.” Martin Carthy and Norma Waterson’s marriage in 1972, the year that Martin became a member of the reformed Watersons, marked the coming together of two vital strands in the history of the English folksong revival.

The Waterson:Carthy extended family is often described as the “First Family of English folk music,” sometimes even as the “Royal Family.” Martin Carthy and Norma Waterson’s marriage in 1972, the year that Martin became a member of the reformed Watersons, marked the coming together of two vital strands in the history of the English folksong revival.

Martin Carthy started off in the London folk scene of the late Fifties and early Sixties in the wake of England’s “skiffle” fad. He adopted a distinctive English guitar style that he developed, impervious to the folk purists who asserted that a guitar had no place in the English tradition, in his work with the Thameside Four and the 3City4. Having established his presence, he then began to perform and record very widely, sometimes solo, often with violinist Dave Swarbrick.

(Incidentally, Topic Records have recently re-issued on CD the celebrated recording that Martin made with Dave Swarbrick and a second guitarist, Diz Disley, in 1967, Rags, Reels and Airs, which is often claimed to have inspired the folk rock that Fairport Convention began to play when Dave Swarbrick joined that band shortly afterwards.)

Both Bob Dylan and Paul Simon were spellbound by Martin’s music when they visited London in the early ‘Sixties. Dylan acknowledged that his “Bob Dylan’s Dream” was set to the tune of Carthy’s version of the ballad “Lord Franklin”, but there have long been accusations of “rip-off” over Simon’s allegedly unscrupulous treatment of Martin, who taught “Scarborough Fair” to the American musician. Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel then proceeded to record it with enormous success but never a word about where they had acquired the song.

As the most prominent of the younger revival singers and musicians who came along in the wake of Bert Lloyd and Ewan McColl, Martin Carthy has also been associated with every new phase of the evolving tradition, playing solo and with Swarbrick, but also in such diverse formations as the Albion Band, Steeleye Span and Brass Monkey. His contribution was formally recognized in 1998 when he was named in the Queen’s official Honours List as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (the order still exists, even if the Empire doesn’t!), the citation mentioning his services to folk music.

Norma Waterson, meanwhile, served her apprenticeship in Northeast England, in a group composed of her sister, brother and cousin, singing traditional songs unaccompanied. The family lived in Hull, a slightly remote seaport with an important fishing industry and a significant agricultural hinterland — an ideal place, in other words, for the coming together of varied musical traditions.

The Watersons, in a series of recordings and through regular performance, and along with the roughly contemporaneous Young Tradition, re-established a thread of polyphonic singing in English music that had almost died out, with the notable exception of the music kept alive by successive generations of the Copper Family of Rottingdean in Sussex. They established a folk club and built up a large and loyal following in East Yorkshire (where Martin and Norma still live). Now that the Watersons and the Young Tradition are no more, it is encouraging that this format has been renewed more recently, in a slightly smoother style, by the trio Coope, Boyes and Simpson. Martin Carthy, as has already been noted, added unaccompanied singing with the Watersons to his other accomplishments and appears on their later recordings.

The end of the Watersons as a musical group gave Norma Waterson and Martin the opportunity to try out new activities (Brass Monkey probably being the most striking), and when their daughter Eliza emerged as a gifted violinist with an interest not only in singing the old songs but also in seeking out forgotten tunes, Waterson:Carthy was born, to universal acclaim.

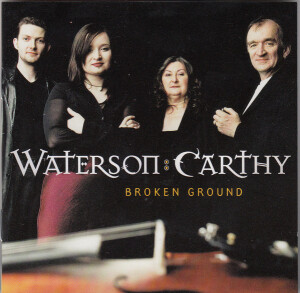

However, the regular praise heaped on their work has not led them to rest on their laurels, and their output of fine music remains astoundingly prolific and unceasingly original. However many of their recordings you own, however often you see them perform, they come up with something new every time. Broken Ground, their third album under the Waterson:Carthy name, is the latest in a regular flow of new recordings from this hardworking clan.

As regards their individual projects, in 1998 Eliza Carthy’s double CD Red Rice, with its combination of the traditions learned from her parents and the modernity that is only to be expected of a musician in her twenties playing with instrumentalists of her own generation, made many people sit up and listen.

Almost simultaneously, her father Martin Carthy put out Signs of Life, a mixture of traditional material and carefully chosen contemporary songs, all performed solo, with Martin’s “folk” voice and judiciously economic guitar-picking giving a strong unity to the mix.

Then earlier this year Norma Waterson released her second solo album The Very Thought Of You, a series of biographical songs about well-known musicians coupled with songs associated with them. (One of them was Richard Thompson’s new song about the Irish vaudeville tenor, Josef Locke, whose obituary I have coincidentally just read before sitting down to write this review.)

This stream of outstanding music continues with Broken Ground, in which parents and daughter are joined by melodeon player and additional vocalist Saul Rose, who is, through his marriage to Eliza’s half-sister Lucy, another member of the family. Incidentally, both Eliza and Lucy have recently had babies, so we can confidently expect the dynasty to be continued into the next millennium.

The new recording is, moreover, produced and engineered unobtrusively (in the best sense of that word), by yet another family member, Oliver Knight. Ollie previously engineered and mixed Waterson:Carthy’s second album Common Tongue, as well as playing electric guitar on Red Rice and also on Eliza’s 1996 recording Heat, Light and Sound.

The new CD opens with two real stunners. First, Eliza performs a haunting version of “Raggle Taggle Gypsies,” a song that most English folks over 35 probably learned at school, but not to this tune, which I have never previously heard. The melody, slower than those usually adopted for this family of songs (which includes the variants “Gipsy Davy” and “Blackjack Davy”), came originally from the Norfolk singer Walter Pardon, who also died only in the past year or so. The first two verses, sung more slowly than the rest to a spare accompaniment from Saul’s melodeon, set the mood very effectively before the tempo picks up and the other instruments join in.

Norma’s opening offer is the equally ethereal “Bay of Biscay,” a wistful song, ideally suited to her voice, about a drowned seafarer who returns to haunt his mourning lover. Eliza’s resonant violin sets the ghostly mood in a style reminiscent of a slow air.

We then hear the first of three sets of dance tunes that separate the songs on the album. In each of these sets, Eliza’s fiddling predominates. The combination of violin and viola with Martin’s distinctively understated guitar style, honed over many years of fiddle and guitar work with Swarbrick, and Saul Rose’ squeezebox, works very well on these tunes, most of which are of English origin, although Scotland and even Quebec are also represented. The time signatures of some of the dances — hornpipes in 3/2 and 9/4 time — would have even Dave Brubeck scratching his head.

Martin’s first vocal contribution is his own amended version of a Somerset song, “The Lion’s Den.” Continuing the trend of perverse time signatures, he dispenses with the 5/4 time of the original ballad collected by Cecil Sharp and sings and plays in a freer tempo that owes more to speech patterns than to musical structure. The song is about a latter-day Daniel willing to demonstrate true love by proving his courage.

The following song “Fare Thee Well Cold Winter,” a duet for Norma and Eliza, provides a perfect opportunity to appreciate the interplay between the voices of mother and daughter. The same harmonious combination, led by Eliza’s singing, is found in “The Forsaken Mermaid.” One of the most striking characteristics of this record is the emotional power of the slow songs. The contrast in timbre between Norma’s “lived-in” voice and the fresher singing of her daughter really brings out the beauty (and frequently the sadness) of the generally unfamiliar (to me) songs on this disc.

I would not want to give the impression that there is anything banal or predictable about this recording, but anyone who is familiar with Martin Carthy’s work will expect some token of his political engagement. On this CD, it comes, somewhat unexpectedly, with Norma on lead vocals, in the form of “We Poor Labouring Men,” a defiant assertion of the importance of the working masses.

This is immediately followed by another staple ingredient, namely a religious hymn, without which no recording by Waterson:Carthy now seems complete. Indeed, the Watersons once recorded a whole LP of popular hymns called Sound, Sound Your Instruments of Joy. On this new CD, the “Ditchling Carol” from Sussex, sung a cappella, manages to associate this hymn-singing tradition with the aforementioned political concern, through its emphasis on the plight of the poor at Christmas. If I have any complaint about this recording, it is a mild dissatisfaction with what the available voices produce without instrumental backing, compared with the erstwhile Watersons in their prime (or the comparable Young Tradition, whose The Holly Bears The Crown from 1969, featuring Shirley and Dolly Collins, provides, for me, some definitive examples of unaccompanied carol-singing).

The final song on the CD, “The Bald-Headed End of the Broom,” which pops up once the last instrumentals have been played, is a “bit of fun,” as I heard Carthy call it in concert last year. It encourages men to shun marriage if they wish to avoid having the item in the title applied vigorously to their pates. The long instrumental introduction, actually a dance tune from Bampton in Oxfordshire — the source of numerous Waterson:Carthy songs — gives Eliza, Saul and Martin scope to display their instrumental skills, while the ride-out brings in the Phoenix New Orleans Parade Band — who, despite their name, appear to be neighbours of Waterson:Carthy — end the CD on a jovial note.

I may have given the impression that I like this CD. Well, the fact is that I adore it. Those who are familiar with Martin Carthy’s work will know how well he writes the accompanying liner notes to his recordings. This CD is no exception. If it is true, as I wrote in my opening paragraph, that Waterson:Carthy are a royal family, I think a comment of Martin’s on “The Lion’s Den” could be suitably applied to them: Martin says the song “contains an interesting notion of what constitutes Royalty. And it sure as hell ain’t defined in blood terms.”

(Topic, 1999)