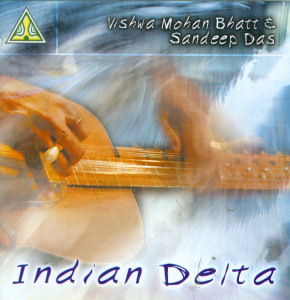

Born in Rajasthan, Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt studied traditional Indian music with the greatest teachers. He even spent time with Pt. Ravi Shankar. He even invented his own instrument. Combining the traditional Indian veena with a Hawaiian guitar, he created an instrument that bears his name: the mohan veena is a guitar shaped box with 19 strings. Three are melody strings, four serve as drone strings and the other 13 are sympathetic strings. This is a loud and ringing instrument that possesses the playability of the guitar and provides the nuances required for ragas. It has a carved arched spruce top, mahogany back and sides, and a mahogany neck with a flat, non-fretted rosewood fingerboard. My own guitar is made of precisely these woods, which I can verify possess magnificent sonic qualities. With all those strings, the tension is tremendous; total pull being well over 500 pounds! Bhatt has an interesting instrument, and he plays it brilliantly. He won a Grammy Award (for 1995’s duet album with Ry Cooder A Meeting by the River); he has also recorded with Taj Mahal, Bela Fleck and members of Los Lobos. On Indian Delta he shares billing with tabla player Sandeep Das.

Born in Rajasthan, Pandit Vishwa Mohan Bhatt studied traditional Indian music with the greatest teachers. He even spent time with Pt. Ravi Shankar. He even invented his own instrument. Combining the traditional Indian veena with a Hawaiian guitar, he created an instrument that bears his name: the mohan veena is a guitar shaped box with 19 strings. Three are melody strings, four serve as drone strings and the other 13 are sympathetic strings. This is a loud and ringing instrument that possesses the playability of the guitar and provides the nuances required for ragas. It has a carved arched spruce top, mahogany back and sides, and a mahogany neck with a flat, non-fretted rosewood fingerboard. My own guitar is made of precisely these woods, which I can verify possess magnificent sonic qualities. With all those strings, the tension is tremendous; total pull being well over 500 pounds! Bhatt has an interesting instrument, and he plays it brilliantly. He won a Grammy Award (for 1995’s duet album with Ry Cooder A Meeting by the River); he has also recorded with Taj Mahal, Bela Fleck and members of Los Lobos. On Indian Delta he shares billing with tabla player Sandeep Das.

The tabla is an Indian drum; actually two drums, one being the treble drum (tabla) and the other being the bass drum (dagga). Played with the fingers and using palm pressure, an amazing range of tones can be produced on these drums. Sandeep Das is a master. Together, on this live recording, these two virtuosi challenge each other again and again.

Indian music is an essentially spiritual exercise. When Ravi Shankar played rock venues he tried to establish this foundational truth. It is also largely improvisatory within the structure of the piece. Each player goes forward pushing and stretching the boundaries, challenging the other and yet so sympathetic to his partner’s progress that a unity of mind and purpose is realized. Bhatt’s success in America is predicated by the collaboration with Ry Cooder. On that album they played improvised pieces, as well as songs from Cooder’s repertoire. The Western structure limited Bhatt’s improvisation but the exercise forced Cooder to look deep inside himself. It is a remarkable album. Indian Delta adheres to classical Indian structure, and apart from the titular reference to the blues, (and the echoes of bottleneck referenced by Bhatt’s playing) this album may be harder for a Western audience to appreciate.

The Indian scale is not what our Western ears are used to. The repetitions we appreciate in our pop music are nothing like the seeming aimlessness our untuned hearing apparatus is confronted with on an album like this. Clearly these two musicians are experts. Clearly they are playing wonderfully. But not everyone will hear the virtuosity, because it is in a context we may not be prepared for. The live recording is clear and bright. There are only short and few audience noises. Given a chance, you will find yourself drawn into this music.

It is not danceable, you will not be whistling the tunes, or snapping your fingers even though a maestro of percussion is present. It is meditative, beautiful, challenging and the mohan veena cuts through like a sabre. World music for people looking to experience something new!

(Sense World Music, 2003)