There were, in the middle of the last century, over 1,000 languages spoken in Africa, grouped into four large families, not counting creoles and pidgins (estimates have actually ranged as high as 3,000 altogether). This does actually have something to do with the debut album by Vieux Farka Touré: when one speaks of “African traditions,” it is well to remember that those 1,000 languages reflect as many cultures and subcultures, which means there is no such thing as “an African tradition.” The songs of Tunisia are not like the songs of Namibia or the songs of the Ituri Forest; traditional dance music in Nubia will be quite different from traditional dance music in Nigeria (Nigeria itself, in fact, is home to at least four major cultural traditions). And so when we talk of the music of Vieux, we are talking about music that stems from the traditions specifically of Mali, interwoven with strands that come from other parts of Africa, from Europe, from the Middle East, and that we can recognize in some American music.

There were, in the middle of the last century, over 1,000 languages spoken in Africa, grouped into four large families, not counting creoles and pidgins (estimates have actually ranged as high as 3,000 altogether). This does actually have something to do with the debut album by Vieux Farka Touré: when one speaks of “African traditions,” it is well to remember that those 1,000 languages reflect as many cultures and subcultures, which means there is no such thing as “an African tradition.” The songs of Tunisia are not like the songs of Namibia or the songs of the Ituri Forest; traditional dance music in Nubia will be quite different from traditional dance music in Nigeria (Nigeria itself, in fact, is home to at least four major cultural traditions). And so when we talk of the music of Vieux, we are talking about music that stems from the traditions specifically of Mali, interwoven with strands that come from other parts of Africa, from Europe, from the Middle East, and that we can recognize in some American music.

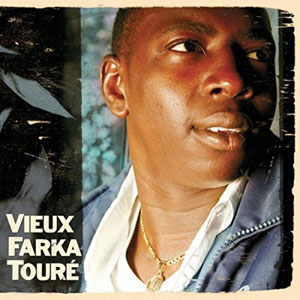

Vieux is the son of Ali Farka Touré, one of Africa’s major musicians from any tradition. His own music, which his son carries on, was called by Martin Scorsese “the DNA of the blues.” His recordings have won several Grammys as well as numerous other awards. What was to me most interesting to learn about both Ali and Vieux is that they are noted as guitarists, which is not an instrument I often think of in connection with African music of any tradition. It may be indicative of something that Spanish is widely spoken among the Bamana people of Mali. Then again, it may not, although I would venture to say that in addition to influences from within Mali between the various peoples who live there, and their neighbors in Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, and The Gambia, we cannot forget assimilations from European and Muslim traditions. And of course, none of this sort of thing ever works completely one way, which is why there is some merit to the idea that the blues grew out of Malian music.

“Enough!” you say. “Enough of these languages and traditions and influences — what about the music?”

OK — that’s fair.

I will say right at the beginning that this is one of the most intelligently constructed collections I’ve ever had the pleasure of hearing. Even though there is a distinct feeling of “blending” from the first track, “Sangaré,” what we hear first are songs that are recognizably “African” — the vocal styles and modes are not exactly like those I have heard from other African artists, but they have a very strong sense of tradition to them, even though the instrumentals have a definite link to jazz. (I might also add, to the delight of those who relish such anomalies, that the second track, “Dounia,” displays rhythms that are as seemingly European — Celtic or Balkan, in fact — as the singing is most definitely not.) The progression seems to move more and more toward jazz without ever quite becoming jazz — somewhere in a territory that lies between jazz and blues, perhaps — more familiar, more like the idioms we are used to, until by the time we get to “Courage,” near the end, we are definitely in blues territory. (And what an incredible song that is! The vocals by Issa Sory Bamba are riveting.) The final track, “Diabaté,” featuring Vieux on guitar and Toumani Dabaté on kora, might just as easily have been an instrumental track on a Robin Trower or Eric Clapton “unplugged” album — except that the music never loses that sense of “other.”

I will also add that Vieux need take second place to no one as a guitarist. Ali recorded two tracks for this album before his death in March, 2006, and like his father’s, Vieux’ playing is fluid or crisp as necessary, fluent, subtle, and absolutely flawless. His command of the music is extraordinary.

Yep — you guessed it. I really like this album.

(World Village, 2006)