Crossroads. Everybody knows the story about Robert Johnson at the crossroads, selling his soul to the Devil in exchange for the ability to play guitar like a fiend. But the real crossroads in American music is gospel. Gospel music is the crossroads where so many of the strains of American music meet, mingle and increase. Gospel mingled with the blues and gave us R&B, soul and funk. Negro spirituals mingled with white southern vernacular hymns (themselves tracing their lineage to Europe) and produced bluegrass. Jubilee quartets begat country-gospel quartets, which a boy from Tupelo mixed with blues and hillbilly and a back beat and taught America’s white kids to rock.

Crossroads. Everybody knows the story about Robert Johnson at the crossroads, selling his soul to the Devil in exchange for the ability to play guitar like a fiend. But the real crossroads in American music is gospel. Gospel music is the crossroads where so many of the strains of American music meet, mingle and increase. Gospel mingled with the blues and gave us R&B, soul and funk. Negro spirituals mingled with white southern vernacular hymns (themselves tracing their lineage to Europe) and produced bluegrass. Jubilee quartets begat country-gospel quartets, which a boy from Tupelo mixed with blues and hillbilly and a back beat and taught America’s white kids to rock.

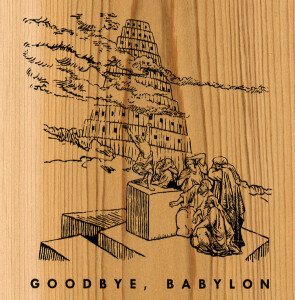

But don’t take my word for it. The evidence is here in this mother-lode of gospel. The Goodbye, Babylon set has almost six hours of some of the most important gospel recordings of the 20th century. From obscure field recordings to major-label sides by some of the biggest names in popular music, it’s here. From blind axe-murderers singing behind prison walls to schoolgirls singing in the parlor, it’s here. From bluegrass to western to spirituals to blues shouters, Grandpa Jones to Mahalia Jackson, it’s all here.

This is the sound of the American South, the song of joy that springs from the region’s tortured soul. The root of gospel is the spiritual, which incubated in the hothouse of slavery. Rhythms and song forms remembered from Africa were grafted onto the vernacular hymns of Christianity, and became a code language that disguised the longing for freedom under the forms of piety. But by the time these recordings were made, beginning in the mid-1920s, a great mixing had taken place, with wondrous results.

The set includes six CDs. Five are of songs, the sixth of sermons. The five song discs are organized thematically:

1 – Introduction.

2 – Deliverance Will Come.

3 – Judgment.

4 – Salvation.

5 – Goodbye, Babylon.

At first glance, the organization seems haphazard, with bluegrass nestling up next to pentecostal shouts, cowboy songs and parlor songs sharing space with the cadences of Sacred Harp sings, jazz bands following string bands, rank amateurs preceding seasoned professionals, and 1920s field recordings followed by crisp studio works. But the thematic organization works in the best interests of the music, demonstrating the relationships among these seemingly disparate art forms that would be masked if looked at chronologically or by genre.

The sheer volume of works is daunting. Each of the five music discs has at least 26 tracks, some as many as 29. In the following descriptions, I’ll point to some of the songs that really speak to me, but that isn’t intended as a slight to those I don’t have time, space or energy to mention here.

Disc 1 Introduction

The Introduction disc is just that, an overview of what’s to be found on the following four. Highlights: The hair-raising title track, in which The Rev. T.T. Rose and singers in his congregation turn their backs on worldly things in favor of the godly life; Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “All I Want is That Pure Religion”; Washington Phillips singing “Lift Him Up That’s All,” in 1927, accompanied by a strange instrument like an autoharp or harpsichord — with a back beat, this’d be rock ‘n’ roll; the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet’s “Rock My Soul”; The Rev. Gary Davis’s “I Belong to the Band – Hallelujah!” from 1935, some kind of blend of proto-rap and talking blues; the Carter Family’s “River of Jordan,” the flip side of their hit “Keep on the Sunny Side” (which shows up on Disc 5); and “O Day,” by Bessie Jones and the Sea Island Singers, a fife-and-vocal shout recorded by Alan Lomax in 1960 — the latest recording in the set.

Disc 2, Deliverance Will Come

This disc deals with the theme of waiting on God to deliver you from sin, or slavery, or The World. Brother Claude Ely kicks it right off with “There Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down,” a white singer’s response to the singing style of Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Jaybird Coleman delivers a bluesy “I’m Gonna Cross the River of Jordan” accompanied by harmonica. The Trumpeteers, another jubilee quartet, sing an early type of doo-wop in “Milky White Way.” A Parchman Farm inmate named Jimpson sings a wood-chopping song, “No More, My Lord,” recorded by John Lomax — the type of song that helped make the O Brother, Where Art Thou soundtrack so popular a few years ago. The string band A.A. Gray and Seven Foot Dilly give a rousing rendition of “The Old Ark’s a Moving.” Elders McIntorsh and Edwards blaze through “Since I Laid My Burden Down.” Blind Willie Davis plays a mean slide guitar on his version of “When the Saints Go Marching In.” And the calypso band, Roaring Lion with Cyril Monrose String Orchestra, gives an incredible performance of “Jonah, Come Out the Wilderness.” Calypso gospel, who would ever suspect such stuff existed in 1938?

Disc 3, Judgment

Judgment, as in Judgment Day, the Day of Reckoning, when the saved will get to turn in their earthly bodies for heavenly ones; it also stands in as the symbolic idea of release from slavery, entering into the Promised Land. This one opens with the oldest track, “Down on the Old Camp Ground,” a “coon shout” by the Dinwiddie Colored Quartet, recorded in 1902 — remarkable for the quality of the recording as well as the performance. Edward W. Clayborn is accompanied by some very bluesy slide guitar on “Your Enemy Cannot Harm You (But Watch Your Close Friend),” which draws its message from the lesson of Judas’ betrayal. There’s more strong slide guitar on Blind Willie Johnson’s “Lord I Just Can’t Keep From Crying,” complementing his powerful gravelly voice. The Jubilee Gospel Team gives an a capella version of the “dying bed” song called “Lower My Dying Head.” Flatt and Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys sing it high and glorious on “That Home Above,” with sublime and subtle guitar picking from Lester Flatt. Great brother vocals from Roosevelt and Aaron Graves spice up “I’ll Be Rested.” The gospel-blues connection doesn’t get much closer than “Got Heaven in My View” by the splendid singer and guitarist Louis Washington. Listen to Sister Mary Nelson’s “Judgment,” and see if you don’t think Rod Stewart copied her vocal style. The great Bukka White, singing as Washington White, belts out a beautiful “I Am In the Heavenly Way.” Dock Walsh, a discovery of Ralph Peer, plays Hawaiian-style lap-steel banjo on “Bathe in that Beautiful Pool.” And for some country-western gospel, there’s “In the Land Where We’ll Never Grow Old” by the Maddox Brothers and Rose, and “I’ll Have a New Body,” by Hank and Audrey Williams and the Drifting Cowboys. This was one of Hank’s most popular sacred numbers on the various radio shows for which he recorded transcriptions in the late ’40s.

Disc 4, Salvation

This one focuses on Jesus as the savior. Thomas A. Dorsey is accompanied by Tampa Red on the laid-back “If You See My Savior,” and Skip James is accompanied by an organ on “Let Jesus Lead You.” The Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet is always irresistible, and “Found a Wonderful Savior” is no exception. Mother McCollum is likewise irresistible for her song “Jesus is my Air-o-Plane.” The Tennessee Mountaineers are a large choral group, and their “Standing on the Promises” is well enough sung but would be unremarkable were it not the last side recorded by Ralph Peer in his historic first session in Bristol, Tenn., where he discovered the Carters and Jimmie Rodgers. The Rev. Gary Davis plays extraordinary guitar and sings passionately on “I Am the True Vine.” But the most remarkable performance on this disc is by a total amateur, a young woman named Dorothy Melton doing a solo unaccompanied vocal performance of “I Want Jesus to Walk With Me.” This lovely folk spiritual comes from an old Folkways release.

Disc 5, Goodbye Babylon

Here the sinner is advised to leave behind his sinful ways before it’s too late. The compilers could be forgiven for slacking off on the quality on this fifth disc, but they don’t. Among the treasures here is the spiritual made immortal by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., “Free At Last.” Dock Reed and Vera Hall Ward turn in a stirring unaccompanied rendition of this powerful old-style song. blind Willie McTell plays some mean 12-string slide guitar on “I Got to Cross the River of Jordan.” The Monroe Brothers sing a sweet “Sinner You Better Get Ready.” Josh White, who was to become a central figure in the folk revival of the ’50s, sings and plays a beautiful “I Don’t Intend to Die in Egyptland.” Blind axe-murderer Jimmie Strothers, singing on the Parchman Farm for John Lomax, gives a stirring rendition of “We Are Almost Down to the Shore.” The Carter Family’s original “Keep on the Sunny Side” is here, as well as The Georgia Peach’s “When the Saints Go Marching In.” And Sister Rosetta Tharpe rocks and swings on “Strange Things Happening Every Day.”

OK. I don’t like all of it. Many of the songs by white singers seem weak or saccharine-sweet up against the powerful spirituals or Delta-blues style gospel. Sacred Harp singing is hard to record well under the best circumstances, and it’s not much fun to listen to in these old recordings. And I’ve never really appreciated the extreme melisma of Mahalia Jackson and others who draw out a single verse of, say, “Amazing Grace” to several minutes in length. On recordings, that is. All of these styles can be extremely exciting in a live setting.

Disc 6, Sermons

These are performances every bit as much as the songs on the other five discs. Many of them, in fact, are as much song as sermon. There are 25 of them, and they range from humorous to hair-raising. Just about every major label and most of the regionals are represented, and a full gamut of denominations, from the more sedate Baptists to the tambourine-shaking holiness preachers of the Church of God in Christ. Even a cursory listen to this disc will give you insight into the rhetorical styles employed by a wide range of present-day African-American leaders and politicians.

The discs are accompanied by an excellent book that gives track-by-track information on the songs, written and researched by some of the top names in roots music, led by Steven Lance Ledbetter and Dick Spottswood. It all comes in a wooden box with a sliding lid (although the CDs themselves are in heavy paper sleeves that won’t take up much room on your shelves), complete with a couple of tufts of raw cotton, a reminder of the circumstances under which this music was born. A classy and artistically valid package, excellent documentation, and most of all, superbly chosen and presented music, Goodbye, Babylon is a precious jewel among music box sets. Learn more about it at the Dust-to-Digital website. And you can learn more about the small labels that released much of this music originally, labels like King and Gennet, in Rick Kennedy and Randy McNutt’s book, Little Labels — Big Sound.

(Dust-to-Digital, 2003)