Brendan Foreman wrote this for Folk Tales.

Brendan Foreman wrote this for Folk Tales.

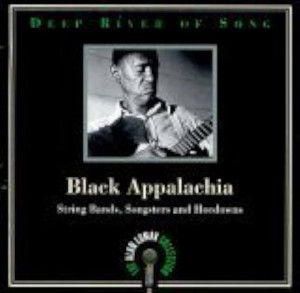

In 1978 Alan Lomax, looking back at a decades-long career of field-recording, began to review the huge library of music that he and his father, John Lomax, had compiled in the 1930s and 1940s. The resulting document — 12 albums under the title Deep River of Song — displayed the full variety and beauty of the African-American folk song at a time of great decline in the interest and knowledge of such music. Rounder, as it has with the Southern Journey series, has begun reissuing these albums. currently, it has published three of them: Black Appalachia, Black Texicans, and Bahamas 1935. In Black Appalachia Lomax concentrated on the folk songs of the African-Americans living throughout the Appalachian chain.

The sheer variety of songs here is daunting; there are fiddle reels, work chants, square-dancing numbers, hoedowns, blues, as well just straightforward folk songs. What makes this CD so interesting is that the Lomaxes (travelling with famed bluesman Leadbelly) recorded these songs at a time of great transition for the American folk song. The current crop of rural musicians were taking all of the various American idiomatic styles — the blues, country, ragtime, swing — and melding them to create new sounds.

The effect to the listener is the feeling of watching a tradition grow and, at the same time, preserve itself. So, while we do have standard American folk songs like the hoedown “Cripple Creek” and the square-dancing number “Soldier’s Joy,” we also get a tune like “Black Bayou,” which combines a Western-style of fiddle-playing with ragtime.

Another interesting aspect of this disc is the cross-racial influences that it reveals. It is very significant that a number of the songs on this disc eventually became bluegrass standards, e.g. “Soldier’s Joy,” “Arkansas Traveler.” Indeed, many of these songs were popular among both whites and blacks: “Skillet Good and Greasy,” a song describing a poverty-laden yet determined mountain life, and “Eighth of January,” a very old song celebrating the Battle of New Orleans.

There are heart-breaking songs on this disk, such as “Pauline,” a prison work song, sung by an inmate Allen Prothero. John Lomax worked hard to have him released early from prison, but sadly Prothero died of tuberculosis before the process could be completed. There is also the wildly vulgar “Poontang Little, Poontang Small;” and, lastly, we are treated to two Depression-era blues songs “The Red Cross Store” and “How Long Blues” by Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee, two very major black musicians of the time (in fact, Leadbelly joins them in the very last song).

It is unfortunate that this CD isn’t quite as accessible as the Southern Journey discs. Clearly, field recording equipment wasn’t quite as good in the ’30s and ’40s as it was in the late ’50s; and so there is a harshness to the sound of the recordings that’s missing (thankfully) in the later Lomax collections. But, those who are willing to bend their ears to this CD will discover a world of hardship and beauty where the trials and tribulations of the times, as well as the joys, were turned magically into songs for all to hear.

(Rounder, 1999)