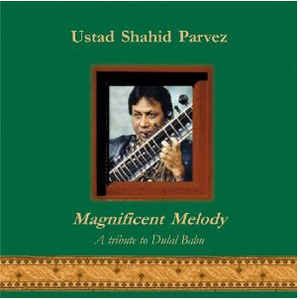

Shahid Parvez began studying the sitar at age four, and gave his first performance at age eight. He belongs to the seventh generation of the Etawa gharana, a tradition begun in the early nineteenth century by Sahebad Khan. In Shahid Parvez’ hands, the tradition combines the so-called vocal and instrumental styles of performance to create a fluid and versatile idiom.

Shahid Parvez began studying the sitar at age four, and gave his first performance at age eight. He belongs to the seventh generation of the Etawa gharana, a tradition begun in the early nineteenth century by Sahebad Khan. In Shahid Parvez’ hands, the tradition combines the so-called vocal and instrumental styles of performance to create a fluid and versatile idiom.

The Raga Darbari is a court piece, a Hindustani raga reputedly from the master Tansen, of the time of the Mogul Emperor Akbar. Parvez begins the alap with a series of rippling glissandi that lead into a spare, almost broken series of short phrases that gradually link together into longer sections; the overall effect is thoughtful, almost pensive, although there is a bit of underlying tension. It is also a lengthy alap: Parvez begins to pick up the tempo as a lead-in to the vilambit gat some 26 minutes into the work, and is not joined the by the tabla for another four or five minutes. The vilambit, too, is not the fast-driving, multilayered, intense sort of experience my previous exposure to classical Indian music has prepared me for: there are flashes of fire, but the overall mood is still almost languid — rather like lying out at night watching shooting stars.

Raga Shahana is widely considered to be a derivative of Darbari, a raga for the later part of the night, and shares its spare, pensive mood. However, at a bit over ten minutes, it is somewhat more easily digestible. The alap is still thoughtful, almost hesitant in places, while the vilambit is intense and lively — Anindo Chatterjee’s tabla is singularly adroit, providing a rich rhythmic counterpoint to Parvez’ sometimes astonishing arpeggios.

Parvez’ playing is, indeed, fluent, fluid, and masterful — one can almost hear the “singing” on which his school of performance is based; and, although the Raga Darbari is exhausting for more-or-less novice Western ears, there is a lot there if you happen to have an hour or so to investigate classical Indian music. One could wish the booklet notes were slightly more informative, particularly in delineating the various sections of the two ragas — I think it is perhaps beyond anyone but the serious student to be able to differentiate among the enormous number of named variations of melodic and rhythmic patterns in Indian music.

Be that as it may, for this listener Parvez’ approach is slightly different, lyrical and fluid with a good use of tension in the initial sections, and well worth hearing.

(Felmay, 2004)