The manuscript for the Messe de Tournai was discovered in the nineteenth century in the library of Tournai Cathedral. Its existence, as is so often the case with manuscripts of this period, owes as much to chance as anything else, while, as essayist John Potter points out, the existence of the Mass itself probably owes as much to a decision of the compiler as any intention by the composers. The parts of the Mass are stylistically divergent, and in fact the Gloria, Credo, and Ite missa est probably date from the thirteenth century, while the remainder is from the fourteenth. The association of the parts owes as much to use as to design: the singers of the time were obviously happy with the arrangement, and so the Mass was written down that way.

The manuscript for the Messe de Tournai was discovered in the nineteenth century in the library of Tournai Cathedral. Its existence, as is so often the case with manuscripts of this period, owes as much to chance as anything else, while, as essayist John Potter points out, the existence of the Mass itself probably owes as much to a decision of the compiler as any intention by the composers. The parts of the Mass are stylistically divergent, and in fact the Gloria, Credo, and Ite missa est probably date from the thirteenth century, while the remainder is from the fourteenth. The association of the parts owes as much to use as to design: the singers of the time were obviously happy with the arrangement, and so the Mass was written down that way.

Potter’s essay, although it gives a sense of having entered the conversation in the middle, is a fascinating look at the history of the Mass as a form and the rise of polyphony in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The present recording also includes monophonic music from a thirteenth-century collection of Laude from Cortona; the laude are not liturgical pieces, but come under the heading perhaps of spirituals. As Potter points out, the chant would have been familiar through long and repeated hearing; the polyphony of the Mass movements would have been new and wonderful. The combination was obviously as pleasing to its audience as it is to us. Potter notes that the singers chose to treat this as contemporary music, which only points up the universality of music to begin with.

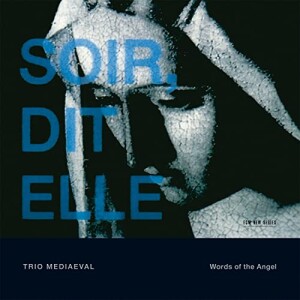

There is in this Mass, as in others, meaning far beyond the simple musical experience. The themes of love, death and sacrifice (common, it would seem, to most religons) are brought sharply to the fore in the penultimate grouping of the Agnus Dei, followed by the final lauda, a lament of Mary for the death of her sacrificed son, followed by Ivan Moody’s “Words of the Angel,” composed for the Trio Mediaeval in 1998 and inserted here, exhorting Mary to rejoice because her son has defied death. And then the Ite missa est – the Mass is over.

The Trio Mediaeval – Anna Maria Friman, Linn Andrea Fuglseth, and Torunn Ostrem Ossum – was formed in 1997 in Oslo. Although their primary focus was on early music, they have broadened their scope considerably to include a number of contemporary works in their repertoire. One is struck in this recording by the clarity and transparency of their voices in singing music that was originally intended to be sung by men, a point that is stressed by Potter in his essay. The fact that the voices are soprano and alto rather than tenor and baritone really makes little difference here – there is the same otherworldly feeling to the music that one hears in chants rendered by male choirs, although there is an ethereal quality to some sections that I’m not sure male voices could challenge. The transitions from monophony to polyphony are seamless, and move from a sense of limitless space to a surprising intimacy without a hitch – it is a remarkably beautiful recording.

One thing that would have been helpful, although not a condition of the music itself: the texts are printed in the original Latin, with one in a French early enough to seem closer to Italian than modern French. Potter notes that one of the Latin laude is secular and overtly political, while the French text sung at the same time is a love song. It would have been nice to have these commentaries in a language in which I am more fluent. Potter’s essay, however, if sometimes confusing – one is not sure at some points just exactly which work he is discussing – is full of information about the Messe de Tournai and medieval practice in liturgical music in general, with fascinating tidbits about the chanciness of preservation of manuscripts.

This is very peaceful music, partaking of all the qualities mentioned above and leaving room for quiet contemplation, which I’m sure must have been its original intention. Beautifully done.

(ECM, 2001)