This set of five classic Dave Brubeck discs is one of two, five-CD sets released by Sony Masterworks in celebration of Brubeck’s 90th birthday on December 6, 2010. The other is Dave Brubeck’s Original Album Classics – Jazz Goes To College, Brubeck Plays Brubeck, Gone With The Wind, Brandenberg Gate: Revisited, Jazz Impressions Of New York.

This set of five classic Dave Brubeck discs is one of two, five-CD sets released by Sony Masterworks in celebration of Brubeck’s 90th birthday on December 6, 2010. The other is Dave Brubeck’s Original Album Classics – Jazz Goes To College, Brubeck Plays Brubeck, Gone With The Wind, Brandenberg Gate: Revisited, Jazz Impressions Of New York.

This one focuses on the Brubeck Quartet’s explorations of various time signatures, a saga that was instrumental in moving jazz beyond the genre’s standard 4/4 swing beat, and in deepening the audience’s understanding and appreciation of these different beats. This is the “classic” version of Brubeck’s quartet, featuring bassist Eugene Wright, drummer Joe Morello and alto saxophonist Paul Desmond.

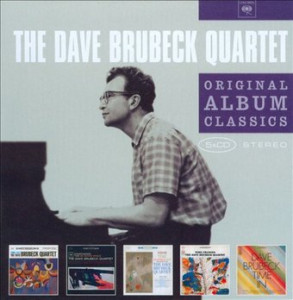

It starts with Brubeck’s classic 1959 album Time Out, which features his most famous piece, “Take Five.” Also in the set is the followup, 1961’s Time Further Out; 1962’s Countdown: Time in Outer Space; 1963’s Time Changes; and 1966’s Time In.

The CDs are packaged in replicas of the original albums, including the covers and rear-cover liner notes. (They’re cool, particularly the modern-art front covers, but the notes on the back covers are hard — in some cases all but impossible — to read.)

This series of “time” albums played a key role in making Brubeck one of the most popular pianists in modern jazz — he was already one of the most influential and respected. Brubeck, who grew up on a California cattle ranch and initially studied veterinary science, had been playing for audiences since a stint in the Army in the 1940s. He and his quartet spent much of the 1950s growing their audience by touring and playing at colleges and universities across America.

Time Out, the second of three albums Brubeck released in 1959, was intended as an experimental album, but went on to become one of the most popular and biggest-selling jazz albums in history, largely on the strength of the single, Desmond’s “Take Five.” But “Take Five” is the third track. The album opens with a whirling dervish of piano notes in 9/8 time, the beginning of “Blue Rondo A La Turk.” Based on melodies and rhythms Brubeck heard on a trip to Turkey, it gallops along in Balkan dance style until getting to the development section in a swinging four that starts with a sax solo, followed by a lengthy piano bit, then a section in which the sax in 9 and piano in 4 swap the lead for two measures at a time, before coming to a rousing close.

“Blue Rondo” is probably the most rhythmically adventurous of the album’s pieces, followed by “Take Five,” which is all in 5/4. Desmond reportedly claimed that he wrote the piece with the quartet’s drummer Joe Morello in mind, after he heard Morello warming up backstage in 5/4 one night. “Strange Meadow Lark” is in 4/4 after a free-flowing introduction. Most of “Three to Get Ready” alternates between 3/4 and 4/4, and all the quartet’s members get a chance to shine on it. I find Morello’s brushwork on this piece subtly delightful, and bassist Wright plays a key role in establishing the rhythm. “Kathy’s Waltz” uses misdirection, starting with a long section in 4/4 before switching to 6/8 (also called double-waltz time), and then combines the two, with Brubeck playing in a swinging 4/4 while the bass and drums click along in 6/8. “Everybody’s Jumpin’ ” employs a similar trick, alternating between 4/4 and 6/4, and parts of it indeed do jump. And the final track, “Pick Up Sticks” is in a steady 6/4. It’s easy to see why Time Out was (and remains) so popular. This is cool jazz at its best.

Time Further Out was intended as a followup to Time Out, and takes the exploration of exotic rhythms ever further. In his excellent liner notes, regarding the 5/4 signature of both “Far More Blue” and “Far More Drums,” Brubeck notes the use of five-beat time in African American field hollers and the like, and goes on, “This African heritage of jazz deserves far more attention.” The album opens, however, with “It’s A Raggy Waltz,” which as Brubeck explains is neither a rag nor a waltz, but a 12-bar blues in a ragged waltz time. This is a highly engaging piece, with loads of interplay between the piano and drums, reminiscent of the rag-influenced works of Gershwin and others in the ’20s and ’30s.

“Bluette” is another blues in waltz time, this time much more straight, slower, and very blue and romantic, with a melodic structure that borrows ideas from Chopin. “Charles Matthew Hallelujah” is a syncopated, celebratory piece in a fast 4/4, written on the occasion of the birth of Brubeck’s fifth son and sixth child. “Maori Blues” is in a fast 6/4, with some of the most interesting piano work by Brubeck, as his melody surfs over the top of a drum-and-bass rhythm that at times sounds like it’s in 4/4. “Unsquare Dance” is great fun, its 7/4 rhythm (the quartet’s first use of this signature) set by the bass, handclaps and drumsticks tapping on the sides and rims of the drums; it’s one of Brubeck’s most playful melodies. After the similarly upbeat “Bru’s Boogie Woogie” in 8/8, we’re treated to 9/8 rhythm of “Blue Shadows In The Street,” which could be from the soundtrack of a film noir. This CD of Time Further Out has two bonus tracks, including a version of “It’s A Raggy Waltz” recorded live at Carnegie Hall, and a studio cut, “Slow And Easy (A.K.A. Lawless Mike).” With or without the bonus tracks, it’s a charming album, and essential Brubeck.

Countdown — Time in Outer Space came out in 1962, and was dedicated to astronaut John Glenn, whose successful orbital flight took place that year. It’s pretty far out! The title track is in 10/4, its melody a traditional boogie-woogie with two extra beats added, but it begins and ends with a section in which Brubeck and Morello (on timpani) alternate 10-beat measures. That’s followed by a piece whose title is its time signature, “Eleven Four.” It was composed by Desmond, and is a good companion piece to “Take Five.” “Why Phyllis Waltz” is a blues that features some complicated interplay among the players, who alternate between 3/4 and 4/4 time signatures, with both occasionally going on at the same time, all apparently improvised in the studio. After those three pieces of between two and three minutes each comes the quartet’s lengthier interpretation of “Someday My Prince Will Come” from Disney’s Sleeping Beauty. They’d been playing the piece for several years, and it was the first in which they experimented with time signatures. The basic rhythm is in 3/4 set by Morello’s high-hat and brushes, but Brubeck and Desmond slide in and out of 3 and 4 over this rhythm, and Morello even sometimes plays a solid 4 on the kickdrum; Brubeck says in the liner notes that he plays in a different key with each hand on one chorus.

The next two tracks, “Castilian Blues” and “Castilian Drums” are both in 5/4. Then there’s a suite of varied time pieces from a ballet Brubeck was composing. “Fast Life” is in 4/4 with an occasional foray into 3/4; “Waltz Limp” is a dance by a character who has lost one shoe; “Three’s A Crowd” puts together three dancers, each dancing in a different time; and “Danse Duet” again segues back and forth between 3 and 4. “Back To Earth” brings it back down with a standard four-beat blues. This CD release has a bonus track, a live version of Brubeck’s tribute to Earl Hines, “Fatha.”

Time Changes from 1963 continues in the quartet’s series of time-related albums. The first side had five tracks that demonstrated the combo’s growing mastery of various time signatures, but the second was something different: a concerto for jazz quartet and orchestra. The five shorter pieces don’t break much new ground, but occasionally mine a little deeper. “Iberia” is in a fast 3/4. the sunny and upbeat “Unisphere” is in the unusual 10/4 time. “Shim Wah” in 3/4 is the first piece by drummer Joe Morello that the quartet recorded. “World’s Fair” draws on New Orleans rhythms, laying down a repeating 13-beat series, with two measures in 3/4, one in 4/4 and another in 3/4; only once in the four-minute piece does that pattern vary, with the 4/4 coming at the end of the series. “Cable Car,” also in a fast 3/4, was inspired by San Francisco’s famous trolleys.

The quartet introduces the orchestral piece with a three-minute “Theme from Elementals,” which helps in understanding the orchestral work. The melody changes from a languid 3/4 to a quicker waltz time, and near the end of this piece you notice that the drum and bass are playing a rhythm in 4/4 under the 3/4 melody. That section is echoed in the main composition with the orchestra playing in 3/4 and Brubeck pounding out a 4/4 rhythm on the keyboard. Brubeck really got to show off his chops as a composer and arranger with “Elementals,” and the quartet, especially he and saxophonist Desmond, demonstrate impressive improvisational skills against the backdrop of the orchestra. Heady stuff for a guy who almost got kicked out of the conservatory because he couldn’t read music.

Time In is the final in the series of “time” albums, and in 1966 it marked the quartet’s 15th anniversary; this classic lineup had been together for eight of those years, but would only last another two. Time In is the only album in the series whose cover is not a modern art work. Both the first two tracks start with lovely slow piano introductions: “Lost Waltz” as a waltz that soon kicks into an upbeat blues in standard time and “Softly, William, Softly” remains a ballad throughout, with Desmond playing a beautiful melodic section. The title track is another polyrhythmic piece, with Brubeck playing a loping foxtrot over the rhythm section’s double-waltz time. “40 Days” in a fast 5/4 is an excerpt from a religious oratorio Brubeck was working on at the time, about Jesus’s temptation in the wilderness. “Travellin’ Blues” is another solid blues in 4, “Lonesome” another standard ballad. “He Done Her Wrong” in a fast 10/4 is the quartet’s take on the old “Frankie and Johnny” tune. The album originally ended with the cool, swinging “Cassandra,” mostly in a fast 4 but having a couple of sections in which bassist Wright and Brubeck play at half of Morello’s tempo.

This version of the CD has three bonus tracks, the playful “Rude Old Man” featuring Wright on the melody; the slinky, bluesy “Who Said That?”; and a Morello workout, “Watusi Drums” in a fast 6/8 for the drummer against a 4/4 walking beat by Wright and a harmonically and rhythmically colorful melody line from Brubeck.

From the tone of the liner notes on Time In it is obvious that some of the jazz world backlash against Brubeck had set in by this time. Credible jazz musicians were supposed to be struggling in obscurity apparently, but Brubeck was immensely popular. He churned out compositions practically in his sleep, and on the evidence of these classic albums he maintained a consistently high quality. And he and the quartet sold hundreds of thousands of albums. This and its companion Dave Brubeck set are not just valuable testaments to Brubeck’s legacy — though they are that — but they’re great fun to listen to.

(Columbia/Legacy, 2010)