Exactly 56 years ago I was perplexedly listening to this new album by my favorite group. I was 10 years old and had been a fan of The Beatles for what had only been two years but seemed like several lifetimes, so many albums and singles did they release in that time. I’d picked up their first U.S. Capitol single, “I Want To Hold Your Hand/I Saw Her Standing There,” in late December 1963, and their first U.S. album Meet the Beatles shortly after that when it was released in January of ’64. Then The Beatles’ Second Album in the spring; Something New in the summer, possibly for my birthday in August (skipping A Hard Day’s Night which in the U.S. was a movie soundtrack album padded with instrumental versions of the handful of songs that were cut specifically for the film); Beatles 65 for Christmas in 1964 (again, skipping the non-canonical documentary album The Beatles Story); Beatles VI in the summer of ’65; Help! sometime after that – maybe I received these two around the same time, possibly again for my August birthday; and finally, Rubber Soul for Christmas in 1965. My lucky parents hadn’t had to worry about what to get me for birthdays and Christmas for two whole years.

Exactly 56 years ago I was perplexedly listening to this new album by my favorite group. I was 10 years old and had been a fan of The Beatles for what had only been two years but seemed like several lifetimes, so many albums and singles did they release in that time. I’d picked up their first U.S. Capitol single, “I Want To Hold Your Hand/I Saw Her Standing There,” in late December 1963, and their first U.S. album Meet the Beatles shortly after that when it was released in January of ’64. Then The Beatles’ Second Album in the spring; Something New in the summer, possibly for my birthday in August (skipping A Hard Day’s Night which in the U.S. was a movie soundtrack album padded with instrumental versions of the handful of songs that were cut specifically for the film); Beatles 65 for Christmas in 1964 (again, skipping the non-canonical documentary album The Beatles Story); Beatles VI in the summer of ’65; Help! sometime after that – maybe I received these two around the same time, possibly again for my August birthday; and finally, Rubber Soul for Christmas in 1965. My lucky parents hadn’t had to worry about what to get me for birthdays and Christmas for two whole years.

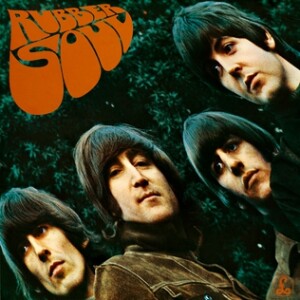

So as 1965 turned to 1966 I was faced with a Beatles album that seemed radically different than any that came before. Starting with the cover, its distorted, dark photo of four faces, the bulbous melting words in the upper left corner saying only “Rubber Soul.” Nowhere did it say The Beatles, and these four somber faces were framed by what seemed to be much longer hair, above brown suede leather jackets. OK, so on the back cover it did say The Beatles and there were more normal photos of them smiling, smoking, etc., so yeah, it must be them.

But the music. Many of the songs didn’t sound much like anything I’d heard from them before. I didn’t have the musical sophistication then, or the vocabulary, to describe it. I couldn’t have described the difference between an electric guitar and an acoustic one. But a lot of these songs are fully acoustic, starting with the opener “I’ve Just Seen A Face.” Paul’s jaunty ditty is a country song! Just add a mandolin and a banjo and it’s bluegrass. In fact it was almost immediately covered by the Charles River Valley Boys and then The Dillards, beginning a long line of bluegrass versions. In the U.K. it had been on the Help! album that came out a few months earlier. In spite of its lack of bass guitar and the use of brushed snares rather than sticks by Ringo, it really hums along and is a great potboiler (as George Martin would say) to start the album. Although of course the U.K. album began with … but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Next up is John’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).” Again, all acoustic guitars, no drums but some kind of shaker, and … what was that other sound? I had no idea what a sitar was, although I’d heard them on the U.S. version of Help!, which was a soundtrack album as opposed to a pure studio LP as in the U.K. This is probably the most adult song they had yet recorded, and I think I was a bit put off by it. I mean, it’s a very mature theme, right from the very first line, “I once had a girl, or should I say she once had me.” Ask your average 10-year-old American boy what that means. Also, what’s Norwegian wood? She has to work in the morning, so he crawls off to sleep in the bath? I was familiar with the trope from old-fashioned comedy skits, so I got it, but … I still didn’t get it. This was never released as a single, but I seem to remember hearing it on the radio. There have been a number of cover versions, and it seems to have become one of those enigmatic Lennon songs that are emblematic of The Beatles’ relative sophistication among ’60s pop groups.

“You Won’t See Me” opens with a crash, and finally, there are some stabbing electric guitar and some rudimentary piano chords. Lovely backing vocals from John and George behind Paul’s double and triple tracked vocals. This could have been on any of their previous few albums, a solid teen love song, with a bit of girl group influence in those “ooooo-la-la-la”s. … And then, what’s THAT sound? George’s “Think For Yourself” opens with the fuzz bass. I was already fond of George, and this song cemented my regard for him. It’s a great dance tempo, it’s acerbic without being downright bloody mean the way John could be, and Paul and John’s falsetto harmonies just kill.

The sequencing! The way “The Word” leaps right off the vinyl after the final honking note from the fuzz bass is brilliant. The fuzz bass plays an upward triplet in unison with Ringo’s snare, there’s a brief moment of silence, and the piano makes a mirror image three note run downward to begin John’s enigmatic song about love. Once again, a Lennon song is in a much more mature vein than the others, lyrically and sonically. A heavily syncopated beat pits staccato stabs from the Stratocaster and snare against boogie-woogie piano figures and Paul’s galloping bass line to create a loping R&B chorus; the verses’ plodding downward quarter notes on the Strat leave plenty of room for John’s forceful declamation of his enlightenment to the word, love. I appreciated its overall catchiness, but the esoteric lyrics and sophisticated arrangement were a bit over my head.

Things slow down for the final track on side 1, Paul’s sing-songy “Michelle.” We’re back to entirely acoustic instruments except for the lounge-jazz guitar solo in the middle eight and the outro. This was a really popular song on AM stations in the heartland, the moms all liked it, but there’s not much to it. Lovely harmonies, though, and a very strong lead vocal by Paul. The only time I’ve ever really liked this song was when I had a crush on a Michelle.

Opening side 2, John’s “It’s Only Love” has always been one of my favorite Beatles songs. I find its structure immensely appealing, the underlying rhythm of the strummed acoustic guitar and the downward running single note counterpoint of the phased electric again sounds rather like a country or folk rock song, but the highly syncopated verses are more R&B. Lyrically it splits the difference between a teenage love song and a slightly more adult lament, and John’s double tracked vocal performance is beautiful; his upward-downward swooping falsetto on the final note makes me swoon. (This one also was on the U.K. version of Help!)

Another John song on top of that, yet one more angsty ballad, “Girl,” with Lennon’s electronically enhanced deep inhalations after each sighing iteration of “girl” … Another fairly mature theme to this one, perhaps at least subconsciously influenced by difficulties in his rocky first marriage. I didn’t relate to this one very much, especially the rather whiny bit about how “a man must break his back to earn his day of leisure.” But once again the backing chorus is masterful and the eighth note-quarter note counterpoint from the two acoustic guitars during the final verse, coupled with Ringo’s smothered ride cymbal crashes make this another superb arrangement.

The impeccable sequencing shows again when Paul’s rocking “I’m Looking Through You” launches next. What sounds like a pure folk-rock song from the acoustic intro becomes something more with the discordant organ chords and Strat riff between each verse. It’s a bit of a toss-away of a song, but they give it a lot of life with little touches like the handclaps and harmony vocals.

Starting life as a deep cut, John’s nostalgic ballad “In My Life” has become a staple of soundtracks and playlists. I didn’t really connect with it until I hit my late 20s, which is about the age John was when he wrote it. It’s easy to think of this as a Lennon solo song, but throughout there are three-part harmonies, subtle electric guitar touches, creative but muted bass from Paul – and Ringo’s drumming really makes this song. I mean, it’s hard to play drums on a slow song in a way that isn’t hokey or intrusive or just wrong, but Ringo nails it perfectly.

“Wait” is an unremarkable song for the most part, except that it’s the first (only) on the album on which John and Paul share the vocals, John on the verses, all three on the chorus and Paul on the bridge verse. George does some nifty work with what sounds like a proto wah-wah pedal, an effect I could not figure out until many years later when I learned about pedals.

Album ender “Run For Your Life” is problematic, isn’t it? I’d probably listened to enough country music to recognize that the whole “rather see you dead than with another man” trope was just that, though I didn’t have that vocabulary yet. But even as a young boy I recognized how wrong-headed John’s possessive jealousy was. Still, this song rocks mightily, and it’s a great way to end the album. The great electric guitar riff and a really strong vocal performance by John almost override its creepiness. Until the next news story you see about a bloke violating a restraining order and killing his ex. Musically this song evokes nothing so much as The Monkees, particularly their smash “Last Train To Clarksville,” but of course the subject matter would never have flown with that American band.

Rubber Soul remains the one Beatles album whose U.S. version I prefer to the U.K. The biggest difference that everybody notices is that the U.K. version starts with “Drive My Car,” which totally knocks the rest of the album’s acoustic vibe off track. As does the inclusion of “Nowhere Man,” which in the U.S. was the A side of a single. My two favorites on this album, “I’ve Just Seen A Face” and “It’s Only Love,” were lifted from the U.K. version of Help! (I’ve never thought they fit there all that well). It is too bad that there’s no Ringo song on the U.S. Rubber Soul – the first album without one – especially since the countrified “What Goes On” would fit just fine although its arrangement is kind of weak. Likewise, George’s “If I Needed Someone,” with its Byrdsian jangly guitar and lush harmonies, would be a good fit – especially if they’d cut one of the unnecessarily repeated verses.

But as it is, the American Rubber Soul is such a solid, compact, enjoyable album. It may not have been apparent at the time, but it shows the Beatles beginning to pivot away from teenage love songs into more mature fare, which would become glaringly obvious on their next album Revolver.

(Capitol/EMI, 1965)