Patrick O’Donnell wrote this review.

Patrick O’Donnell wrote this review.

If there is magic in music, Susan McKeown surely is a mage, for how else can her enchanting vocals and entangling arrangements be explained? Her amber tones weave a spell when first they are heard, and you are not yourself again until the music comes to an end.

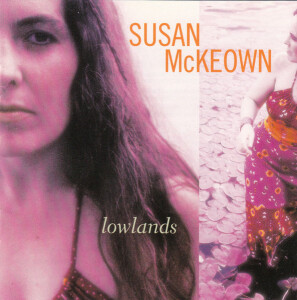

Lowlands, her sixth album, is one of the most fascinating works I have listened to in what seems ages. There isn’t a bad song – not even a mediocre one – on this 12-track CD. Her practice of combining traditional works with non-traditional instrumentation gives each piece a very unearthly feel, while keeping their roots quite grounded in the fertile Celtic soil.

McKeown honed her skills as a student of opera in Dublin and a student of the streets as a busker. After she moved to New York in 1990, she built renown through her work with the Chanting House, but musical differences led the original members to split. She now performs as a solo artist, backed by whatever artist strikes her musical whimsy, as this album deftly illustrates. From bouzouki to bass, kora to kaval, cahones to caxixis, banjo to bodhrans, instruments from all around the world are combined to give almost every song a fresh, original sound.

The disc opens with “An Nighean Dubh/The Dark Haired Girl,” a traditional Scottish song of the sea steeped in adventure and eroticism. This up-tempo version, arranged by McKeown and Jamshied Sharifi, features guitar, kora, kaval, fiddle, whistles, clarinet and bass clarinet, electric bass, synthesizer, and various percussion. The otherworldly sound she conjures gives you some idea of what wonders the rest of the album holds. McKeown, singing in Gaelic, trades back and forth between refrain and verse, giving the illusion of back-up singers and moving the song along as if it were being rocked and tossed by the waves. The clarinets are a doleful presence, seeming to moan like the booming surf under the ship’s bow, a constant reminder that with love and adventure there is always great danger.

The next song, “Johnny Coughlin,” takes a more mournful tone. On her web site, McKeown says she was haunted for some time by this song. Her version proves no doubt just as haunting as any she’s heard. The low whistles and guitar give a feel of drifting on an ocean without a destination in mind nor a care where that ship lands; much the way Johnny Coughlin seems to feel about his life.

“The Hare’s Lament,” a traditional hunting song, is a view through the eyes of the prey as it seeks frantically to escape the jaws of the hounds and understand its plight. Paddy League beats out a fine rapid tattoo on the bodhran, much the way the hare’s heart must be pounding out of its chest as the hunters close in. The bodhran also serves up the illusion of hoofs pounding over the moors.

“Slan agus Beannacht/Goodbye and Farewell” has a Galician feel to it, with hand claps, cahones, accordion and flamenco guitar, not such an odd mix until you consider that this is a traditional song from County Waterford, Ireland. After a short flamenco intro, McKeown starts singing in Gaelic. The transition is almost startling, because the sound, at this point, has a very Mexican, almost Tex-Mex, ring to it. The driving guitar rhythm then becomes tango-like as her lyrics swirl, and soon an accordion kicks in on a new stanza, lilting along as she fills in the background with an Enya-like chant. You’ll probably find yourself clapping or drumming along, bidding life’s troubles farewell, but all too soon the song ends, leaving you wondering what happened. This is one of the most up-tempo songs on the CD – literally and figuratively – and one of my favorites.

The next song, “The Snows They Melt the Soonest,” takes you down a very different path indeed. The simple lament of a man trying to overcome a woman’s scorn and win her love, it is accompanied only by an acoustic guitar (Aidan Brennan) and a fiddle (Johnny Cunningham) that seems almost to wail in grief for unrequited love.

McKeown’s talent for off-the-wall arrangements that mix instruments and style while clicking perfectly never ceases to amaze, and the next song is as good a proof as any. “Nansai Og Ni Obarlain/Young Nancy Oberlin” is sung to an acoustic bass (Glen Moore) and a bodhran (League again) that sounds more like a set of bongos. Listening to this song is like sitting in a beatnik coffee house with some eclectic jazz trio up on stage. McKeown also shows off her writing skills here, as she has a hand in the second verse.

“Lord Baker,” the seventh song on this marvellous album, is the CD’s showcase. Clocking in at 8 minutes and 47 seconds, it’s an opus that sums up all McKeown’s talents, and those of the many musicians who contributed their skills. Jamshied Sharifi again shares arranging credits with McKeown. The tale is that of a nobleman whose wanderlust lands him in a Turkish prison. The Turkish king’s daughter falls in love with him and sets him free. Before he departs, she pledges to wait seven years without marrying if he does the same. At the end of this time plus one week she seeks him out, only to find he has wed that day. Lord Baker realizes his folly, quickly sends his bride of just a few hours home with a very generous amount of gold and falls into the embrace of his true love.

McKeown’s voice, tinged as it is with dark mystique, is perfectly suited to this ballad. Kora, kaval, gaida and clarinets insert more than a touch of pentatonic oriental sound, steeping this song in a very Eastern brew. The end result raises welcome goose bumps. The chanteuse inserts lyrics from three different versions of this oft-heard traditional song; and, according to the liner notes, her version contains some new ones as well.

The only song on this work that doesn’t have traditional roots is the next, “Dark Horse of Ireland.” Written by Liam Weldon, it is both an ode to and a lament against the battle for Ireland’s freedom. McKeown tackles this one a cappella with stunning results. Her powerful voice is clear yet wavers with the raw emotion this song demands, and she delivers it with such a grace and passion that the listener can be moved at once to tears over the horrors of war and a patriotic rage – no matter where your place of birth – against those who seek to use and twist that battle for their own purposes.

Again the album turns to an East Asian sound, this time on another unlikely candidate, “The Lowlands of Holland.” The mournful vocals are accompanied by just the eerily beautiful sounds of an erhu and a banjo plucked very slowly and deliberately.

Switching gears to a murder ballad, McKeown sings the Scottish “Bonny Greenwoodside.” This tale of a mother who gives birth to and then strangles her children is sung in a very straightforward manner, backed only by chanting and percussion.

McKeown saves the two most traditional-sounding works for last, “To Fair London Town” and “The Moorlough Shore.” The first, a story of near-cannibalism on the high seas (there is a happy ending, I assure you), is accompanied by guitar, fiddle, whistles and a very subdued acoustic bass. The second, another lament about lost love, ends the CD on a mournful note, coupled with uilleann pipes, cello and guitar.

McKeown borrowed from quite a crop of musicians on this album, a list too numerous to mention in this review. She has an uncanny ability to recognize just who – or what – will provide a perfect accompaniment on each track. I can only shake my head in amazement at her talent. She is a true musical genius, a rarity in this age of sound bites and two-minute pop hits.

Her sound is possessed of equal parts darkness and light, as much bright and delightful as it is stark and supernatural. She may flesh out a ballad with a small orchestra of sound, or strip it down to its bones. Either way, it becomes a version that likely will stick with you for a long time to come. Let us hope she also records for some time to come.

(Green Linnet, 2000)