What do you think of when you hear the term “sea shanties?” A bunch of guys singing rhythmic songs unaccompanied or with one concertina or fiddle? Or maybe even Rogue’s Gallery, the late great Hal Willner’s superb four disc collection of sea-related songs by an amazing roster of musicians from all over the English speaking world? Well, this isn’t like that.

What do you think of when you hear the term “sea shanties?” A bunch of guys singing rhythmic songs unaccompanied or with one concertina or fiddle? Or maybe even Rogue’s Gallery, the late great Hal Willner’s superb four disc collection of sea-related songs by an amazing roster of musicians from all over the English speaking world? Well, this isn’t like that.

To be sure, the music on Shane Parish’s Liverpool started out at sea shanties, but they’ve been very creatively reinterpreted by this supremely talented guitarist. Parish has spent much of his creative career playing free jazz and prog music, but a little while back began shifting to folk music. His first release along those lines was a 2016 album Undertaker, Please Drive Slow for John Zorn’s Tzadik label – which artfully blurs the lines between free jazz and folk musics, particularly spiritual music from Jewish and other faith traditions. I like his publicist’s description of Parish’s music as “arranging traditional folk music for solo guitar with bursts of improvisation.”

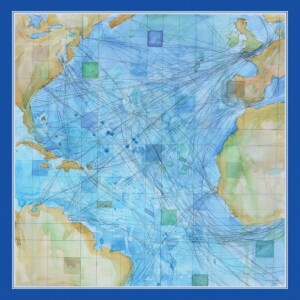

Parish decided sea shanties were right up his alley, and it’s easy to see why. These songs arose from the work songs of mostly British and Irish sailors (with some influence from African call-and-response work songs) in the Atlantic maritime trade of the 19th century. Being sung mostly unaccompanied, they put particular focus on the human voice, and Parish typically builds his guitar arrangements of folk material around the voice, not any of the accompanying instruments.

He had worked up acoustic arrangements of these songs, but on the eve of recording decided to switch to electric guitar. It really works! These densely layered and looped recordings in many ways capture the wildness of the sea and the anxiety that must constantly haunt the human hearts of those who work upon it, particularly in fragile wooden craft, doing incredibly hard labor in harsh, uncomfortable conditions.

So if you think you’re going to hear warm acoustic fingerpicked arrangements of jaunty sea shanties, Parish disabuses you of that notion from the very first, as the opening track “Liuerpul” begins with an electronic squall. This is the song often known as “The Leaving Of Liverpool,” but is only just recognizable as such. Ditto the album’s other bookend, the ninth piece “Rio Grande.” This one is less abrasive though, more aptly described as a deeply ambient meditation – the tune is all but obscured by the tremeloes, drones and rhythmic pulses of sound he draws from his fretboards.

Things are more tuneful in between, by varying degrees. You’ll likely find some songs you know here. My favorite is the sad tale of separated lovers “Black Eyed Susan.” If you know the version of this song that appeared on Anna & Elizabeth’s masterful album The Invisible Comes to Us you’ll recognize Parish’s arrangement, which is based on theirs. Parish very thoroughly describes his recording in the liner notes, so I’ll let him:

Many people have sung this song, but I first heard it performed by Anna & Elizabeth, when I played supporting sets opening for them on two separate occasions. I was moved to tears both times. Elizabeth LaPrelle’s singing and Anna Roberts-Gevalt’s guitar playing combine to give this song a deeply haunting and sparse arrangement.

The melody is so strong that it does not require much dressing to evoke a world of desolate and sorrowful beauty. In my arrangement I break it into phrases for the first section and interject watery responses to each melodic passage, before the song culminates in a driving groove where the melody repeats ad infinitum with only the subtlest of variations in articulation. The light percussion of Michael Libramento accentuates the momentum.

After a couple of short tunes – the trebly “Eliza Lee” and the brooding “Banks Of Newfoundland” played with what sounds like an ebow – we get Harry Belafonte’s “Venezuela.” Libramento lays down a jaunty calypso rhythm and Parish plays the melody on a twangy baritone guitar, over a subtly layered bed of strings and percussion.

“Randy Dandy O” is somehow both sprightly and stately, the melody plucked out on a wildly distorted guitar, its lilting melody muscled aside by forcefully raspy power chords at the turnarounds – with bleary slide guitar passages staggering through like a drunken sailor.

The most elaborate arrangement comes in “Haul Away Joe.” Parish plays the tune, which sounds related to “House of the Rising Sun,” on a rumbling bass guitar with lots of distortion. That melody rolls atop a thick bed that includes a looped ebow-style guitar line and a deeply droning bass sounding like the faraway rumble of the ship’s turning screw. After several minutes Libramento comes in with a full drum kit accompanied by yet more layers of guitar noise, until the wailing strings and crashing toms and cymbals crescendo to a thundering climax.

A weird fluttery backing (which sounds like a synth but we’re assured is all guitar) lends an aura of surreality to the lovely melody of “Santy Anno,” which devolves into a sort of metal wailing, which gives way to that meditative final track “Rio Grande.”

The highlights for me are “Black Eyed Susan” (obviously) and that twangy “Venezuela,” but I like all of this. For the most part it’s not light recreational listening, but fans of boundary pushing guitarists like Bill Frisell and Nathan Salsburg ought to enjoy this quite a lot.

(Dear Life Records, 2022)

Shane Parish is on the web, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.