We live in an era when most of the recordings that any of us buy are put out by multinational megabucks corporations, for which the recording business is only one of a number of activities and has to earn its keep by producing a profit for the conglomerate’s bottom line. It is therefore highly reassuring to come across a new CD, deliberately recorded and marketed for the benefit of what must inevitably be a tiny minority.

We live in an era when most of the recordings that any of us buy are put out by multinational megabucks corporations, for which the recording business is only one of a number of activities and has to earn its keep by producing a profit for the conglomerate’s bottom line. It is therefore highly reassuring to come across a new CD, deliberately recorded and marketed for the benefit of what must inevitably be a tiny minority.

Those of us who like to listen to traditional/acoustic/Celtic and similar genres of music ought to feel constant and undying gratitude for the existence of small labels that fill this niche and, seemingly, manage to remain commercially viable. My shelves, filled largely from British sources, are full of discs from Fellside, Fledg’ling, Park, Cooking Vinyl, Solid, Grapevine, HTD, Green Linnet, Woodworm and so on — not forgetting the granddaddy of them all, Topic Records.

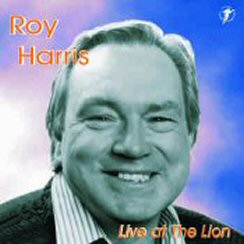

Wild Goose is a little label that exists to serve the small public for English folksong. Roy Harris; moreover, is a sort of human equivalent of such specialist record companies. If it did not sound so much like a weak joke, I would describe him as one of the unsung heroes of the British folk revival and folk club scene. Having encountered folksong while doing his military service in the Fifties, Harris went on to found and run numerous folk clubs wherever he happened to be living at the time, got to know just about everybody on the revival scene and has spent the rest of his life promoting traditional song, without ever becoming rich or famous in the process. Now in his late sixties, Harris continues in the same modest way to keep the faith with his favorite music. Compared with his life, the careers of such “minority” musicians as Martin Carthy or Maddy Prior must appear exceedingly glamorous and exciting.

This is a CD without frills or pretensions. It is a live recording made at the White Lion Folk Club in Wherwell, Hampshire (Southern England). All the singing is unaccompanied, the delivery is perfectly plain, with no vocal tricks or embellishments, and the songs are therefore sung as they must have been by common people for many generations. Harris’s voice is not special, although it has a certain power and he has learnt how to put over a song in a crowded club or pub. His vocal chords betray some signs of fraying with age. Because of the circumstances of the disc’s production, the emphasis is on songs that the enthusiastic audience can join in with. This means either old favorites or, if new, songs with a chorus that can be learnt quickly and easily. As an alternative to songs requiring sung participation, there are also humorous songs, where the crowd’s contribution is to laugh in the right places.

Given the importance of joining in, the CD naturally includes several sea-shanties, including the well known “Blow the Man Down” and “Johnny Come Down To Hilo.” As Harris himself acknowledges in his brief notes, once the crowd gets into its stride he can make up and add on verses to such shanties until he thinks they have had enough. In some places, the audience is clearly familiar enough with the songs to introduce a few simple harmonies, but for the most part it is full-throated unison singing — great fun, no doubt, if you are there, but, sadly, less exciting in recorded form.

Not all the songs are familiar, at least not to me. There is a version of “Foggy Dew” which is not the usual warhorse, for which Harris thanks the late Ewan MacColl, and an American song called “Cambric Shirt” learnt from Laurence Older which, it will come as no surprise to learn, is a very distant cousin of “Scarborough Fair.” Despite the disc’s very English character, Harris is clearly not embarrassed at the inclusion of American material and his version of “The Lion’s Den” is also a transatlantic one. It is interesting to note that in Martin Carthy’s notes on his own version of this song, which appeared last year on his excellent and highly original album Signs of Life, he points out that he has known this song for over thirty years but did not record it until he found an English version!

Again, in keeping with the political flavor of a typical folk club, Harris includes a couple of songs with a transparent social conscience (“When the Coal Comes from the Rhondda” and “Millworkers Children”). To round out the club experience, he also narrates a very amusing story called “The Lazy Farmer,” in which the eponymous hero makes a convincing bid to become a world-beater in idleness by refusing to exchange his survival for two bushels of peas unless someone else shells them.

This CD, which Wild Goose issued in association with the admirable Scottish-based magazine The Living Tradition, faithfully illustrates what goes on in many a local folk club on the nights when there is no important visitor to listen to. I hope that Roy Harris will not resent my adjective. He has, of course, been extremely important in his own way, but I think everyone will understand my meaning. There is a good crowd in, most of them know each other and the singer and most of the songs, they have probably had a few drinks and are in a mood to enjoy themselves in one of the oldest ways known to humankind — with a good singsong that doesn’t require a big name to stoke it up. If you are curious to experience this phenomenon, this is a good CD to do it with. It will not be a big seller, except perhaps among the regulars at the White Lion and friends of Roy Harris, but it is a precious reminder of the enduring power and charm of traditional song.

(Wild Goose Records, 1997)