(This review was written by Gary Whitehouse and Dan Herman in September 1999.)

Any new release by Richard Thompson is eagerly awaited by his minor legion of extremely loyal fans worldwide. But anticipation was especially high for Mock Tudor. It’s his first studio release since 1995’s You? Me? Us? and he’s working with a new production team for the first time since 1986’s Across a Crowded Room. The buzz began to build in early August when the music press on both sides of the Atlantic started running laudatory reviews, and reached a fever pitch when Thompson and band started opening live sets with five or six songs off the disc.

Any new release by Richard Thompson is eagerly awaited by his minor legion of extremely loyal fans worldwide. But anticipation was especially high for Mock Tudor. It’s his first studio release since 1995’s You? Me? Us? and he’s working with a new production team for the first time since 1986’s Across a Crowded Room. The buzz began to build in early August when the music press on both sides of the Atlantic started running laudatory reviews, and reached a fever pitch when Thompson and band started opening live sets with five or six songs off the disc.

What has emerged to answer the expectations was a bit unexpected: a concept album rife with Baby-Boomer nostalgia. Mock Tudor explores the people and places of Thompson’s past, growing up in London and its suburbs in the 1950s and ’60s. Brimming with musical and lyrical echoes of that era, Mock Tudor is the most accessible, most “pop” collection of tunes Richard Thompson has ever released.

Nearly every song on Tudor draws liberally from the musical styles of the ’60s, including skiffle, R&B, Beatlesque pop, Byrds jangle, Who stutters, and even some blues, a real departure for Thompson. Notable by their near-total absence are references to British folk and dancehall music, Django-style jazz progressions, Middle-Eastern and — except for some hurdy-gurdy buried deep in the mix — eastern European influences.

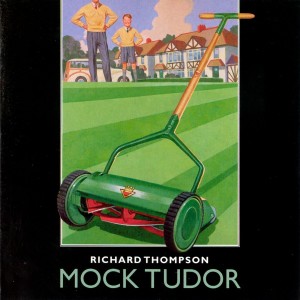

Thompson has further reinforced the nostalgic theme with numerous quotes from fairy tales and children’s books — “One pill to get bigger, another pill to get small”; “I swear by the pricking of my thumbs”; “who’s been sleeping in my bed?” “the golden goose” — as well as radio, TV and films. Even the album art evokes Post-World War II prosperity, with its idealized visions of life in the suburbs: cars, lawnmowers and various household appliances.

The album has all of Thompson’s trademarks: songs about quirky and colorful characters from the wrong side of the tracks; tales of love gone bad told with wry, dark humor; intelligent lyrics; and his own absolutely unique brand of virtuoso electric and acoustic guitar. But gone are the murky settings that have characterized much of Thompson’s ’90s work with longtime producers Mitchell Froom and Tchad Blake. The production team of Tom Rothrock and Rob Schnapf (who have worked with rock acts including Beck, Elliott Smith, and the Foo Fighters) have given these songs a sound like the best records of the ’60s and ’70s: sharp and clear, the vocals out front, drums and bass laying down a solid groove, guitars and other instruments embellishing.

And what songs they are.

“Cooksferry Queen” starts things off in high gear with its swinging skiffle-like beat ably laid down by long-time Thompson collaborators Dave Mattacks on drums and Danny Thompson (no relation) on double bass. Richard’s twanging guitar licks twine sinuously around a swaggering blues harp. And he shows off very strong and confident vocal chops on this rave-up about a small-time ’60s hood enamored of an acid-dropping hippie chick.

From there, Mock Tudor moves from strength to strength.

“Sibella,” a song of mismatched lovers, is propelled by a driving tom-tom beat reminiscent of The Raiders’ 1967 hit, “Indian Reservation.” “Bathsheba Smiles” has a swampy, Gypsy-like feel on the verses and soars into a Stones-like chorus with multi-tracked backing vocals by Teddy Thompson, son of Richard and his ex-wife and former collaborator, Linda Thompson. “Two-Faced Love” has a pulsing r&b groove with an abundant bottom-end supplied by a honking baritone sax and Froom’s keyboards.

This first section of the CD roars to a climax on “Hard on Me,” a throbbing mid-tempo rocker on which Thompson spits out two of his inimitable solos. “Hard on Me” also seems to be a bold declaration of the autobiographical nature of much of Mock Tudor. Thematically and musically, this song closely resembles one of his old standbys, “Shoot Out the Lights,” down to actual quotes in one of the guitar solo sections. But the subject matter — the rage of a teenager toward parents and other authority figures — is much more explicit here, and Thompson has said in more than one interview that the song draws heavily on his relationship with his policeman father.

“Crawl Back (Under my Stone)” has a lot going on. Thompson’s vocals have never been stronger than on this song, a bitter tirade by a man rejected as a suitor because of class differences. It is among his catchiest tunes ever, paying homage to the Beatles and Buddy Holly, with an Everly Brothers-style bridge between the second and third verses. Former producer Froom supplies some humorous touches with swirling accompaniment on the Hammond B3.

“Dry My Tears and Move On” is straight out of Memphis in the ’60s, a Stax-Volt “Big Boys Don’t Cry” to answer the Four Seasons’ song. “My suits got creases and my shoes got shine / Let me know soon, I’ll find a better use for my time…” Are you sure Ray Charles didn’t do this one? If he hasn’t, he should. Thompson frequently uses a horn section on his records, but mostly in the style of English “silver bands,” working class bands that compete among the various towns, mines and mills. Here, though, the horn arrangement is definitely in the Memphis soul style.

“Walking the Long Miles Home” is another soulful but uptempo number about a fellow walking home to the suburbs after breaking up with his city girlfriend. It has one of the record’s best lines: “Got the rhythm in my shoes to keep the blues away.”

“The Sights and Sounds of London Town,” an acoustic number featuring Richard and Danny, continues the nostalgic theme of *Mock Tudor*. An homage to Ralph McTell’s ’60s anthem, “Streets of London,” it offers four vignettes of London street characters. Interestingly, they are set in reverse chronological order, starting in the ’90s with a family woman from the suburbs spending the weekends as a streetwalker in the city, going back through the ’80s and ’70s to a slick-dressing ’60s hustler. Melodically, it’s reminiscent of one of Thompson’s most durable songs, “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” with a catchy, hook-laden chorus.

Two of the slower numbers — “That’s All, Amen, Close the Door” and “Uninhabited Man” — are more in line with the best of Thompson’s ’90s work. Both are deceptively quiet songs, their languor masking a seething cauldron of emotion just under the surface. This is the kind of song that has drawn his die-hard fans and keeps them hanging on: all smoldering angst and pain, couched in bitter metaphor, and occasionally breaking forth in cathartic whip-lashes of virtuoso guitar wrangling.

“That’s All” on the surface is a painful paen to the end of a love affair. With its soaring bridges between the verses, thumping bass-drum line and bluesy feel, this could be a lost Roy Orbison song. On the other hand, in a recent, unusually candid interview, Thompson called the song a plea to fans of the late Sandy Denny to let her rest in peace. (Denny, lead vocalist with Thompson’s Sixties folk-rock group Fairport Convention, died after a fall in 1978.) “She gave as much/As she had to give/Please don’t ask for more…” pleads Thompson in one of the disc’s strongest tunes.

“Uninhabited Man” is a demanding and rewarding song, musically and lyrically. The imagery is complex, drawing on Western and Eastern religion, mythology and fairy tales, to paint a picture of Man without Love. Thompson is a practicing Sufi, and like many Muslim poets, writers and mystics through the centuries, his love songs can also be interpreted spiritually. Thus the uninhabited man is one who is ready to be filled with God’s presence: “What an old dry shell I am … I’m left no skill no art/to meet you heart to heart/you’ll find no me beneath the skin.”

The album ends on something of a down note. “Hope You Like the New Me,” is a bleak and chilling number that explores the psychological need to meld with another by “stealing” their style, laugh, friends, walk, wife and soul. Though Thompson’s wry sense of irony is present as usual (“I stole your jokes, only the good ones…”), one senses that this theme is not entirely a laughing matter to him, given that he has previously dealt with it in two excellent tunes this decade: “Cold Kisses” (from *You? Me? Us?*) and “Slipstream” (from Mirror Blue).

Unlike any of his previous albums, Mock Tudor contains several songs with strong potential for radio play and even hit status. Time will tell whether this recording will finally see Richard Thompson deservedly emerge from cult status, as Bonnie Raitt did earlier this decade with “Nick of Time.” Or is it destined to be yet another Thompson disc on the order of his Shoot Out the Lights (1982) hailed by critics and fellow musicians but largely ignored by the public?

(Capitol, 1999)