“If you ask the average person where they think the five-string banjo originated, the chances are that they would say it came from Kentucky or North Carolina …” (Dick Weissman, from the liner notes.)

“If you ask the average person where they think the five-string banjo originated, the chances are that they would say it came from Kentucky or North Carolina …” (Dick Weissman, from the liner notes.)

Well, Green Man reader, you’re an average person, right? OK, most of our readers are above average, it’s true, but we’re trying to establish a baseline here! So…is that your guess? Banjo … bluegrass … country … the mountains? Let’s see what Mr. Weissman says.

“… the truth is that the banjo was originally an African instrument … so the question that comes to mind is why this African instrument has been assigned to the United States. To put it another way, when did black become white?” (Dick Weissman, from the liner notes.)

Sure enough, Wikipedia’s entry on the banjo traces it back to African sources. Does the name come from the Kimbundu term mbanza or maybe it’s a “dialectical pronunciation of ‘bandore’ ” or even from the “Senegambian term for the bamboo stick used for the instrument’s neck.” The fact is it’s an old design, as old as ancient Egypt, but re-invented in the shape we know now by an American in the 1830s.

There are four-string banjos, five-string banjos, banjo ukes, and each of them has a skin as the resonant top, to give the unique sharp banjoesque sound. Whether used in bluegrass or jazz, country or wherever it might be heard, a banjo adds an immediately recognizable tone. But when you hear it, the first thing you think of is that kid in Deliverance, right? It has an immediate reference to white hillbillies sittin’ on the porch with a jar of mountain dew. It’s a white instrument, and Mr. Weissman is right in suggesting that by adopting the banjo the U.S. turned it into a white man’s tool. When did it become white? I’m not sure, some time in the first half of the 20th Century probably. So, leave it up to Otis Taylor to track down this unique instrument and reclaim it in an essentially black context.

Recapturing the Banjo takes on the challenge of placing the banjo back in rootsier contexts. Taj Mahal did something like this many years ago, in fact. Check out Taj’s Recyclin’ the Blues album, for instance. Taylor says that “the banjo has become so closely associated with folk singers and bluegrass players. Over the years, the instrument just lost touch with its roots, and I’m just trying to re-establish that connection.” Does it work?

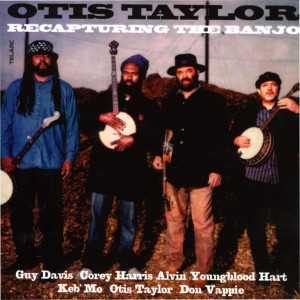

Indeed it does. From the first clawhammer notes of “Ran So Hard the Sun Went Down” which features Alvin Youngblood Hart, Corey Harris and Don Vappie joining Otis Taylor on banjos, and Otis hooting the vocals, through “A Prophet’s Mission” (Hart taking the lead on a tale about Tecumseh) right to death songs (“Simple Mind”) to the Keb’ Mo’ tune that closes the album (“The Way It Goes”) this is an album of moods and melody. The banjo becomes more than simply that percussive, harsh thing in the background. It’s more than the flashy solo bluegrass instrument. It takes on an identity of its own. And you begin to hear subtleties you never thought possible.

Of course the presence of such a fine group of banjo sympathisers helps. Along with Hart, Harris, Keb’ Mo’ and Vappie, there’s Guy Davis on mandolin, guitar and harmonica, Cassie Taylor on bass and Ron Miles on cornet. Add a touch of lap steel here and an electric banjo there, and you have a classic album celebrating a classic instrument. With Otis Taylor’s fine songwriting and leadership this makes for a remarkable listening experience.

OK, maybe it’s not for everyone, but who says music has to appeal to everyone? This is a damn fine album, and one that draws you into a world of its own. An African, American, celebration!

(Telarc, 2008)