What I’m noticing in my journey through “traditional” music is, first of all, tradition is what you make of it (in other words, anyone who works with traditional music is negotiating with the past), and second, there are lots of traditions (which is to say, everyone who works with traditional music is also negotiating with everyone else).

What I’m noticing in my journey through “traditional” music is, first of all, tradition is what you make of it (in other words, anyone who works with traditional music is negotiating with the past), and second, there are lots of traditions (which is to say, everyone who works with traditional music is also negotiating with everyone else).

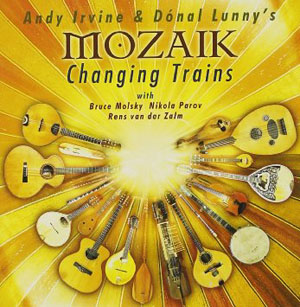

Take, for example, Mozaik. Composed of Andy Irvine (vocals, bouzouki, mandolin and harmonica) and Donal Lunny (vocals, bouzouki, guitar and bodhran), both Irish (by birth or affinity), Bruce Molsky (vocals, fiddle, guitar and banjo), an American folk singer; Rens Van Der Zalm, a Dutch guitarist (who also plays fiddle, mandolin, oud and the low whistle) – who met Irvine in Slovenia, by the way – and Hungarian Nikola Parov (kaval, gaida, gadulka, guitar, whistle, percussion, nyckelharp, and fujra), it’s hardly what I’d call “purist.” (They are joined on this album by Liam O’Flynn on uillean pipes and whistle.)

And yet. . . .

Interestingly enough, in spite of the varying musical traditions brought to bear on this collection, Changing Trains is the album of a number that I’ve listened to that sounds most traditional. It’s just that I’m hard-put to pinpoint the tradition. “O’Donoghue’s,” which opens the disc, is as nearly pure Irish as makes no difference, while “The Wind Blows Over the Danube,” in spite of the title, is as American as Ohio, and probably more so than apple pie. The same goes for “Reuben’s Transatlantic Express.” “The Ballad of Rennardine/Johnny Cuig” gives an interesting twist to the whole idea, with a character that is not at all Irish – not only due to the instrumentation, but also some tricky rhythms that speak more of Eastern Europe than the Isle of the Mighty. (“The Humours of Parov” is a deliberate exercise in contrasts, between the Hungarian 9/8 time “daichevo horo” and the Irish slip jig, also 9/8. It also happens to be richly textured, intricate, and very beautiful.)

There’s not much left to say. Take as a given that the execution of these songs is of sufficiently high quality that I find nothing to complain about, and that Mozaik is, indeed, doing interesting things. There is a range here, of mood and inspiration, that takes us across the world without any pretensions: one gets a real sense that the members of Mozaik have each contributed to the sound and the repertoire through respect for and appreciation of the richness of their individual traditions. They’ve used those traditions as a foundation for music that is rich, sometimes dizzying in its exploration of time and place – because that’s a lot of what’s going on here, exploration, and it’s pretty intriguing. (I can’t begin to describe how it feels to hear the kind of vocal ornamentation in an Irish ballad that one last heard in a sample of Middle Eastern pop. Particularly when it works.)

And it’s like I’ve said any number of times: tradition is something you build on. Which is what Mozaik has done in Changing Trains.

(Compass Records, 2008)