Big Earl Sellar wrote this review.

Do you want the long review or the short one? Here’s the short: Do yourself a favour, go out and buy this disc. Right now.

Do you want the long review or the short one? Here’s the short: Do yourself a favour, go out and buy this disc. Right now.

Here’s the long: John Hurt’s story is one of those magical bits of music history. Recorded by chance by the OKeh label in 1928, Hurt never sought the spotlight like many of his recorded contemporaries: he was just a local musician, the sort of person who was replaced by the radio during the 1930s, when live music became more of a commercial enterprise. Retreating to his hometown of Avalon, Mississippi, he returned to farming, playing the odd dance and living in general obscurity. After having his recordings reissued in the 1950s during the American folk boom, Hurt was tracked down in the early 1960s, finally brought to the spotlight at the age of 71, and recorded for the first time in over 30 years. Although his ’60s career only lasted until his death three years after being rediscovered, his legacy is indelibly imprinted on every finger-picking guitarist since then.

It’s extremely difficult to describe Hurt’s music. Although clearly belonging to the Piedmont Blues camp, his style is far more idiosyncratic; he belongs in the camp of truly unique voices, rather like the Bahamian guitarist Joseph Spence. His self-taught style with its steady bass runs and paraphrases of the melody on the treble strings, all highly syncopated, immediately grabs your attention. His voice is rather reedy, even on those original recordings (reissued on Yahoo). But it’s his presentation that sucks the listener in. He is so laid-back, so relaxed, playing solely for his own entertainment, even in a concert setting. Gentle in a way that other blues artists could only dream of (he makes Rev. Gary Davis sound like Black Sabbath in comparison), Hurt’s music is a measure that all folk and blues pickers measure themselves by, whether they’ve heard of him or not; his stamp has entered the stylistic lexicon the same way that Maybelle Carter’s and Merle Travis’s have. His technique is now part of the general vocabulary of all guitarists, regardless of genre.

Rediscovered (as if he was ever lost!) is a collection of Hurt’s 1960s output for Vanguard. Twenty-four tracks, one voice and one guitar. We should be grateful that no one opted to “fill out” his sound during recording with other instruments. Hurt’s music makes any listener smile; it’s so gentle, so comfortable, even when he deals with the darkest subjects. Part live, mainly studio, with some spoken parts, it’s a great overview of the man’s music and legacy.

All the standards are here, from “Make Me A Pallet On Your Floor” to “It Ain’t Nobody’s Business,” and his anthem “Avalon, My Home Town.” This is music that is related more closely to the later 19th century rural tradition than 20th century blues. The far too short “Stocktime,” a great buck dance, nods to the oldness of this style. Most tracks are either by Hurt or that great music writer “public domain,” with the odd spiritual like “Nearer My God To Thee” receiving the Hurt treatment. “Talking Casey,” his only recorded example of slide playing, is also included. Note that all these tracks were previously released on his four Vanguard records, all of which are in print again.

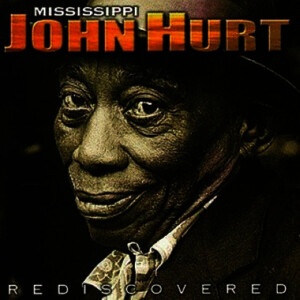

I have a few minor gripes with this disc. First of all, at just over 75 minutes long, it could use some editing: the disc wouldn’t suffer without the live “You Are My Sunshine” or his rather loose (let’s not say sloppy) take of “Goodnight Irene.” Also, the sequence is a tad odd, leaving such great tracks as “Let The Mermaids Flirt With Me” (the happiest song about death this side of Richard Thompson) towards the end. Also, the liner notes are a tad brief, albeit thorough. The sound is passable; I really have a thing for discs that advertise serious digital remixing, and leaving us with surface noise and old analogue tape hiss (“Monday Morning Blues” is particularly dense, sounding like it was mastered off a vinyl version). I have nothing against surface noise (honestly! Despite all my complaints about it over several reviews); it just seems odd to note that, for example, the tapes were “converted to 20 bit digital audio …” when the sound is no better than non-digital mastering (again, see Yahoo’s 1928 Sessions). Great photos, though, especially for the cover shot.

But you really can’t fault this disc too much; Hurt’s too great of a performer, the music is too captivating, and the music is still as timeless thirty years on as it was thirty years after his first recordings. Now that you’ve waded through all that, it boils down to the short review again: Do yourself a favour, go out and buy this disc. Right now. But thanks for reading the long one.

(Vanguard, 1998)