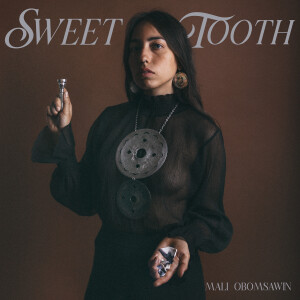

It doesn’t seem enough to say that Sweet Tooth is one of the most emotionally powerful albums I’ve heard this year. Aptly described as “a suite for Indigenous resistance,” this suite from Wabanaki jazz bassist, composer, and songwriter Mali Obomsawin is all about the way Indigenous peoples’ adaptation and resilience have fueled their art and culture – in this case, specifically of Wabanaki people.

It doesn’t seem enough to say that Sweet Tooth is one of the most emotionally powerful albums I’ve heard this year. Aptly described as “a suite for Indigenous resistance,” this suite from Wabanaki jazz bassist, composer, and songwriter Mali Obomsawin is all about the way Indigenous peoples’ adaptation and resilience have fueled their art and culture – in this case, specifically of Wabanaki people.

Mali Obomsawin (who previously played bass, wrote and sang in the contemporary folk trio Lula Wiles) grew up on ancestral land in central Maine, and in Québec on the Odanak First Nations Reserve, where she is enrolled. While studying jazz at Dartmouth College (which was founded in 1769 to “educate” the Wabanaki people), she discovered field recordings of the songs and stories of Wabanaki people (also known as Abenaki and Wampanoag), including some of her direct ancestors, recorded at Odanak, languishing in the archives. Sweet Tooth combines these and other Wabanaki songs with Obomsawin’s own compositions “addressing contemporary Indigenous life, colonization, continuity, love and rage.”

“Telling Indigenous stories through the language of jazz is not a new phenomenon,” Obomsawin says. “My people have had to innovate endlessly to get our stories heard – learning to express ourselves in French, English, Abenaki … but sometimes words fail us, and we must use sound. Sweet Tooth is a testament to this.”

The album is a testament to intersectionality in various ways. Most obviously in its blending of what non-Indigenous listeners might perceive as disparate genres including folk, jazz, Indigenous song, spoken word, and field recording. But also in Obomsawin (o-BAHM-sa-win) herself, as a BIPOC and gender nonconforming person.

Sweet Tooth is Obomsawin’s debut recording as a leader, playing bass and hand drums, singing lead vocals, composing and arranging, and co-producing with musician and teacher Taylor Ho Bynum. Her ensemble includes Bynum on cornet and flugelhorn, Savannah Harris (drums, vocals), Miriam Elhajli (guitars, lead vocals) Allison Burik (bass clarinet, alto saxophone, vocals), and Noah Campbell (tenor, soprano, alto saxophones).

The album is a suite in three movements. The first movement begins with “Odana (The Village)” an homage to Odanak, the Abenaki reservation in Québec where they resettled following colonization of “New England.” It opens with a beautiful brass choir arrangement, then Obomsawin joins in, singing the stately and ancient ballad about the village; as she sings, additional vocalists join in, and the freely improvised accompaniment grows in volume and stridency; this track leads gently into Obomsawin’s composition “Lineage,” which opens with her plucked bass, Harris playing the kit and Bynum improvising on horn around a loose time signature. The nearly eight minute piece passes through solo sections and some free improvisation before fading out with some quiet wordless vocalizing.

The second movement ratchets up the tension (and release). First comes “Wawasint8da,” an old Catholic hymn about Jesus’ “harrowing of hell,” translated into Abenaki by a Jesuit priest. Through a powerful arrangement of vocals and improvised playing, it juxtaposes the peaceful surface of the hymn with the colonial violence under the surface.

Next, “Pedegwajois” opens with a field recording of a pre-colonial tale, “Little Round Mountain,” told by Theophile Panadis of Odanak, first solo then backed by Obomsawin’s ensemble in an uplifting spiritual jazz tune that is my favorite thing on this album.

The third movement opens with Obomsawin’s gentle jazz ballad “Fractions,” the shortest on the album, and wraps up with the longest, the 11 minute, episodic “Blood Quantum (Nəwewəčəskawikαpáwihtawα).” This one moves from a straight-ahead drum solo through some hefty jazz-rock fusion and some Eric Dolphy-like free playing featuring bass clarinet and tenor sax in particular, into the contemporary chant “Nəwewəčəskawikαpáwihtawα,” co-authored by Obomsawin, Lokotah Sanborn and Carol Dana of the Penobscot Nation. The translation by Dana is:

“I stand to face him, I face him defiantly, unflinchingly, I confront him.

We remember our matriarchs

We remember our grandmothers.”

It’s a stirring end to a uniquely powerful recording, and one that I’ll be discovering new meanings and feelings in for some time to come.

(Out of Your Head Records, 2022)

Mali Obomsawin is on this website | Bandcamp | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

My enjoyment of this album was enhanced by Mali Obomsawin’s appearance on two episodes of the Basic Folk podcast: One discussing Sweet Tooth and an earlier episode discussing her personal story, her activism, and her previous folk band Lula Wiles.