While both of these recordings were made by Québec folk musicians, the resulting music displays some differences. Le Vent Du Nord (meaning North Wind) is a band composed of Benoît Bourque (a multi-instrumentalist who appears on accordion, mandolin, jaw harp and bones, as well as backing vocals), Simon Beaudry (guitar and vocals), Olivier Demers (fiddle, with brief forays on mandocello and guitar, plus backing vocals) and Nicolas Boulerice (vocals, hurdy-gurdy, piano and accordion). The quartet is joined by guest percussionist Patrick Graham on two tracks, although the members of the band add percussive sounds themselves in places, including vigorous foot-tapping as well as bones and snare drum. The other guests are bassist François Marion, who appears on 4 cuts, and Daniel Roy, whose whistle is heard on one song. With the obvious exception of the occasional sound of the piano, whose status as a folk instrument is questionable, the instrumentation is largely traditional. Even the piano is heard, unless my ears deceive me, only on “La Valse A Huit Ans” (“the waltz at age 8”), a composition by Bourque, whose solo introduction is soon joined by the rest of the band in a way that reminds one of the music produced by June Tabor’s pianist Hugh Warren, on a set of jigs and on the final number, “De La Chambre A La Cuisine” (“from the bedroom to the kitchen”) — not about what the title implies, as it is purely instrumental.

While both of these recordings were made by Québec folk musicians, the resulting music displays some differences. Le Vent Du Nord (meaning North Wind) is a band composed of Benoît Bourque (a multi-instrumentalist who appears on accordion, mandolin, jaw harp and bones, as well as backing vocals), Simon Beaudry (guitar and vocals), Olivier Demers (fiddle, with brief forays on mandocello and guitar, plus backing vocals) and Nicolas Boulerice (vocals, hurdy-gurdy, piano and accordion). The quartet is joined by guest percussionist Patrick Graham on two tracks, although the members of the band add percussive sounds themselves in places, including vigorous foot-tapping as well as bones and snare drum. The other guests are bassist François Marion, who appears on 4 cuts, and Daniel Roy, whose whistle is heard on one song. With the obvious exception of the occasional sound of the piano, whose status as a folk instrument is questionable, the instrumentation is largely traditional. Even the piano is heard, unless my ears deceive me, only on “La Valse A Huit Ans” (“the waltz at age 8”), a composition by Bourque, whose solo introduction is soon joined by the rest of the band in a way that reminds one of the music produced by June Tabor’s pianist Hugh Warren, on a set of jigs and on the final number, “De La Chambre A La Cuisine” (“from the bedroom to the kitchen”) — not about what the title implies, as it is purely instrumental.

On this CD there are no electric instruments and the performance style is generally unsophisticated, with playing that eschews superfluous ornamentation allied to singing that usually prefers unison to harmony – where there is harmony it remains very simple. This is not in any way meant to denigrate the vocal or instrumental capacities of the musicians, who are extremely good, clearly know what they are doing and where they want to go and produce a highly professional sound. Le Vent is a leading force in folk music in Québec and the repertoire is firmly rooted in tradition. Nine of the 13 tracks consist of traditional songs or tunes, while with one exception the composed material adheres closely to traditional forms. All the songs are sung in French, with the performers sometimes seeming to take a delight in exaggerating their Québec accent. Helpfully, much of the information in the accompanying booklet is given in both French and English and the band’s website offers a choice of either language.

Not only the instrumental pieces and passages but also most of the songs are danceable, with the foot-tapping and step dancing to encourage listeners to start moving their own feet. The least traditional item is “Du Haut Du Balcon” (“from up on the balcony”), a lyrical instrumental that Olivier Demers plays beautifully on acoustic guitar and dedicates to his father. In keeping with the historically rooted nature of the music, the songs deal with subjects that folksongs have always tackled: there are songs about love, bawdy songs (lots of double meanings here if your French is up to it – check “C’Est Une Jeune Mariée,” a song about a young bride whose household chores are all metaphors for a couple’s oldest activity), comic songs, drinking songs and stories of typical kinds – the young couple whose love overcomes all obstacles (in the outstanding title track), the soldier returning unrecognised to his family (“Le Retour Du Fils Soldat”). Some of the songs have apparently been passed down for generations in the Boulerice family.

This recording is evidence, if any were needed, of the vigor of Québec’s musical traditions, and one can only hope that Le Vent Du Nord continues to flourish in the way similarly inspired and motivated bands do in Ireland, Great Britain, Brittany and Galicia. Their support from Canada’s Council for the Arts is particularly welcome when one considers some of the less edifying ways in which governments spend taxpayers’ money.

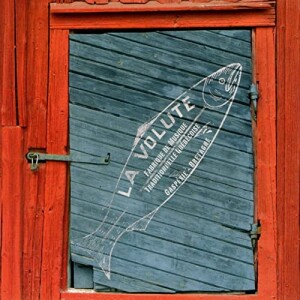

Le Vent Du Nord will not have to compete directly against La Volute (a name that means a kind of spiral) for the title of top group in French Canada, since the latter, although originating in the Gaspé region of eastern Québec, has been based in Brittany since 1995 and shares a promotion and recording company with a variety of Celtic and similar musicians and groups. (I found this information at this website.) You are therefore more likely to encounter them live at one of their frequent appearances not only in Brittany but all over France than you are in Canada.

Le Vent Du Nord will not have to compete directly against La Volute (a name that means a kind of spiral) for the title of top group in French Canada, since the latter, although originating in the Gaspé region of eastern Québec, has been based in Brittany since 1995 and shares a promotion and recording company with a variety of Celtic and similar musicians and groups. (I found this information at this website.) You are therefore more likely to encounter them live at one of their frequent appearances not only in Brittany but all over France than you are in Canada.

There are inevitably similarities between this band’s music and that of Le Vent Du Nord, but perhaps because they are no longer rooted in Quebec, La Volute’s four members have gone looking a little more widely for their repertoire and also add to their musical texture by using an electric guitar in places — but there is no piano. Nevertheless, the musicians present a similar range of skills to Le Vent: Sylvain Fournier sings lead, plays melodeon and harmonica and, once again, taps his feet (providing the only percussion to be heard on this disc); Pierre Sergent plays basses; Philippe Le Gallou plays acoustic and slide guitars and also Telecaster; finally, Pierrick Lemou appears on violin, viola and mandolin. All of the last three also contribute vocals.

Most of the tracks again follow the Québecquois tradition by being eminently danceable even when they are songs rather than instrumentals, and there is again much unison singing. However, both in repertoire and performance style, La Volute dips into music from other parts of eastern Canada and also from Europe, although, surprisingly perhaps, there is nothing obviously Breton on this recording. Unlike Le Vent Du Nord, La Volute does not provide the words to the songs even in French, which is a pity, since it is often helpful to know what the song is about.

Whereas Le Vent Du Nord’s material was all new to me, Volute’s disc includes, among the stand-out tracks, a song about the hardships of deep-sea fishermen (“Les Grands Bancs” – no translation needed, I suspect) that is set to what the booklet describes as a traditional Welsh tune. However, anyone familiar with English hymn-singing will recognize the Irish tune “Slane” to which Jan Struther set her hymn “Lord Of All Hopefulness.” There is often also an Irish feel to the numerous jigs and reels that the band performs. There are also figures borrowed from other musical genres: Lemou introduces some nice jazzy touches on both mandolin and violin in the traditional song “Grand Pierre,” while “Les Grands Bancs” has a guitar solo in a blues-influenced mood contrasting markedly with the overall “trad. arr.” feel.

On the storming title track too, which is about eating cod, Lemou brings an almost Grappelli-like feel to his violin. “Tortillez-Vous Belle” (meaning something like “twist around, my beauty”) is a particularly interesting performance: Fournier sings the verses of this traditional song and the other three sing a unison chorus, all accompanied only by foot-tapping. These exotic touches, as well as the choice of tunes from other musical traditions both inside and outside Canada, often involving in a single composite piece combinations of Québecquois and “foreign” tunes – all these things mark La Volute’s music as having acquired a few more layers than that of their stay-at-home cousins. However, this album also contains the simplest piece of folk music on either of the two recordings: Sylvain Fournier turns in a beautiful, totally unaccompanied version of a traditional song learned from a Gaspé cousin, “Complaint A Mon Frère” (“lament to my brother”).

Even if the overall impression is therefore of an expatriate band that has incorporated a wider range of extraneous influences into their music than the group still based in Québec, this is a generalization, and some of Le Vent Du Nord’s music is stylistically more developed than certain pieces by Le Volute. In any case, there is naturally room for multiple approaches in the field of French Canadian music, just as in other kinds of roots-derived music. Indeed, it is the infinite adaptability of traditional music to new styles, approaches, interpretations, whatever, that keeps me listening to it and wanting to tell others about it.

These two recordings illustrate the vitality of music from Québec: while there are musicians like this around, the tradition is in good hands.

(Borealis Records, 2005)

(CO-Le Label Records, 2005)