Kelly Joe Phelps is firmly located in folk and country blues, but he is one of those musicians who are impossible to pigeon-hole. It’s tempting to describe him by comparison with his myriad musical influences, but that would miss by a mile his originality.

Kelly Joe Phelps is firmly located in folk and country blues, but he is one of those musicians who are impossible to pigeon-hole. It’s tempting to describe him by comparison with his myriad musical influences, but that would miss by a mile his originality.

Let me start, then, by saying that I have seen Phelps play, and such an opportunity is not to be missed. What this fellow does with his fingers and a slide on a guitar laid face-up across his lap, and a twisting skein of sinuous lyrics, is a one-man musical feast. Phelps was a free jazz bassist before taking up the blues; and he claims to never play a song the same way twice. I can believe it.

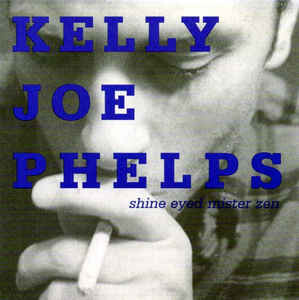

While Phelps is riveting in performance, he can be daunting on record. Shine Eyed Mister Zen, his second full-length CD for Ryko, immediately grabbed my attention, but it took some patient digging to get below the simultaneously dark and shiny surface to the real treasure. That said, now I feel free to start trotting out those comparisons. On first impression, especially the first half of Zen, I imagined Phelps as the spiritual offspring of Bob Dylan and Taj Mahal. Add some strong influence from those crazy uncles, John Fahey and Leo Kottke. Throw in a pinch of Johnny Cash, a dash of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and a generous sprinkling of Woody Guthrie, and you get some idea what he’s all about. He’s a story-telling troubador, with a strong blues and gospel influence.

Kelly Joe Phelps knows just how to milk a phrase — either a lyric or a progression of notes — for all it’s worth. His voice is a warm, golden honey tone, with a bit of a smoker’s huskiness to it. Phelps is rarely content to just sing a song’s lyrics. Like the best of the old Delta bluesmen, he caresses each word and phrase, and occasionally punctuates a line with grunts, moans and other interjections.

The disc opens with an old folk standard, “House Carpenter.” Phelps is scrupulous and generous with his credits, noting that his version of “House Carpenter” was inspired by Clarence Ashley. Oddly enough, The Handsome Family on their 1996 CD “Milk and Scissors” similarly credit Ashley, although their take is wildly different than Phelps’s.

I’m pretty sure this CD was recorded live in the studio, with few overdubs, if any, which makes it all the more amazing. There’s so much going on, even in such a straightforward song as “House Carpenter,” that it’s hard to follow the vocals and instrumentals at the same time. He doesn’t just play a bass-line with his thumb and pick a simple pattern on the higher strings with his fingers — at times it’s rather like listening to Richard Thompson on one of his acoustic gems like “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.” That can’t be just one person playing one guitar!

The CD’s title comes from a verse in the second track, “River Rat Jimmy,” a dream-inspired childhood reminiscence. The imagery is an eerie combination of Dylan and deep, muddy Delta blues. Phelps uses no slide here, just straight finger-picking, as he does on about half of the songs on the CD.

The disc’s second half, starting with “Capman Bootman,” changes in tone a bit. Imagine if you will the kind of song Eddie Vedder and Paul Simon might write if they collaborated, and you might come up with something like “Capman.” “Leave the making sense behind/zen bazooka buddha joe/cornmeal and guitar strings/hates to fly and lives to sing…here he is again, Capman Bootman.” It’s almost jazz scat singing, the way he delivers it.

Phelps’ music has a deeply spiritual element and borrows heavily at times from gospel, especially on penultimate track, “Many a Time,” an uptempo shuffling blues with the repeated refrain “Only believe, thou gonna be saved.” A couple of his mentors are obvious in his choice of songs: the cautionary tale “Dock Boggs Country Blues,” and the album closer, Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene.”

Phelps’ way of approaching a song is most apparent on an old chestnut like “Irene.” He doesn’t just trot out another take, like 100 other versions you’ve heard; nor does he deconstruct it into some post-this or anti-that weirdness. It’s almost the opposite of “deconstruction.” Phelps seems to have a way of stripping away everything but the essence of a song, then performing it in such a way that it seems like it should have always been like that. When he sings in this slow, dark, richly textured cover of “Irene,” “I wish that I’d never seen your face/I wish I was never born,” well, you believe him.

For me, the most accessible song on the album is “Wandering Away.” The playing and the lyric remind me of James Taylor’s best blues cuts. Phelps is a younger man, but when he sings lines like “All these broken promises in a shoebox full of bones,” you know he’s lived the blues.

Jazz-Americana guitarist Bill Frisell in his liner notes says it better than I can when he writes that Phelps “is not just playing ‘at’ the music or trying to recreate or imitate something that’s happened in the past. He seems to have tapped into the artery somehow. There’s a lot going on in between and behind the notes. Mystery.”

Shine Eyed Mister Zen isn’t for everybody. This is adult music. Use with caution. This kind of haunting blues can be contagious. Phelps is on Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube and other platforms.

(Ryko, 1999)