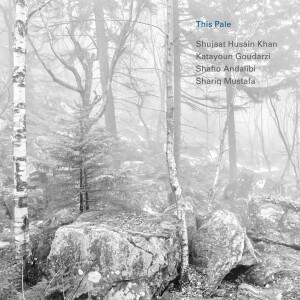

All of the projects by Iranian-American vocalist Katayoun Goudarzi and Indian composer and sitarist Shujaat Husain Khan are emotionally engaging in their own ways. But their 2021 recording This Pale is especially moving. Goudarzi specializes in singing and reciting the ecstatic poems of the ancient Persian poet known as Rumi, which are set to music which is improvised in the studio by Khan along with a few other select musicians.

All of the projects by Iranian-American vocalist Katayoun Goudarzi and Indian composer and sitarist Shujaat Husain Khan are emotionally engaging in their own ways. But their 2021 recording This Pale is especially moving. Goudarzi specializes in singing and reciting the ecstatic poems of the ancient Persian poet known as Rumi, which are set to music which is improvised in the studio by Khan along with a few other select musicians.

The music on This Pale was performed and recorded in response to events that followed the U.S. presidential election of 2016 and the growing levels of intolerance and even hatred that followed in its wake toward immigrants, refugees and even U.S. residents with origins in Muslim majority countries, as well as persons of color in general regardless of origin or religion.

This time out they elected to perform nothing but love poems by Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, a 13th-century Persian mystic bard and Sufi master who has been the best selling poet in the U.S. for 20 years running. They’re joined by Iranian Shaho Andalibi on the ancient end-blown flute known as the ney, and Shariq Mustafa, a fifth-generation Indian tabla player. The four musicins – Goudarzi, Khan, Mustafa and Andalibi – expertly translate Rumi’s shifting flow of emotions through their vocals and instruments.

“I think there are a lot of gut-wrenching sounds throughout,” says Katayoun, “and it’s sort of a reflection of how we felt, all of us. So you would hear it in my voice, you would hear in Shujaat’s sitar, and you would also hear it in the ney. Our hope was that our listeners would hear that humanity and would be able to immediately connect to it emotionally. We thought maybe it would make them more curious about what this album stands for and that, in turn, would develop into a conversation and dialogue.”

I’ve always been deeply affected by Goudarzi’s performances of Rumi’s poetry, as reflected in my reviews of their previous releases Spring, Ruby, and Will You? (with Saffron Ensemble). This outing is no different, and perhaps more emotionally charged, given the selections and the feelings of the musicians as they approached this project. I particularly find the playing of Shariq Mustafa on tabla highlights the range of emotions portrayed in the verses, but all of these musicians are keenly attuned to what their partners are doing and react accordingly. Shujaat Khan’s fleet fingered plucking and Andalibi’s expressive ney in the introduction to “Sweetest” is but one highlight. Goudarzi’s lightly tripping vocals on this song are also notable.

They save the best for last with the song titled “All I’ve Got,” which comes with a particularly good story. The song was inspired by an email Katayoun received from a young woman from Afghanistan. The girl wrote that she followed Goudarzi’s work and loved it. She then confided that her favorite of Rumi’s love poems was the one later sung in “All I’ve Got” and that she will often hum it ever so quietly around the house because she is not allowed to sing. She said she hoped, one day, Katayoun would sing it for her.

“That just absolutely broke my heart!” says Goudarzi, “So on that track, I actually start by humming the song. And then I gradually started to sing in low notes. And by the end, I hit the high notes with all my emotion …because I felt that I wanted her to be heard. And hopefully she’ll hear!”

The piece, in bars with 14 beats, begins with a tender introduction on sitar, then ney, then tabla, before Goudarzi finally hums a few bars and then begins singing. The recording has a spare, lonely feeling and remains low key until near the end when Goudarzi pitches her vocals into her upper register, truly giving it all she’s got. It’s a wrenching performance even on record. I hope the young Afghan woman hears it someday, especially in light of all that has happened between the time this was recorded and its release on Oct. 1. I hope you’ll listen, too.

(Lycopod Records, 2021)