I was 18 years old in 1969, when this record was first released. I was just beginning a lifelong interest in the blues. A friend played Muddy Waters’ The Real Folk Blues album for me, and I was hooked. I had heard the name John Mayall, but had never paid much attention to his music. I knew that Peter Green and Eric Clapton (among others) had started in his band but no-one played Mayall records. You didn’t hear them on the radio.

I was 18 years old in 1969, when this record was first released. I was just beginning a lifelong interest in the blues. A friend played Muddy Waters’ The Real Folk Blues album for me, and I was hooked. I had heard the name John Mayall, but had never paid much attention to his music. I knew that Peter Green and Eric Clapton (among others) had started in his band but no-one played Mayall records. You didn’t hear them on the radio.

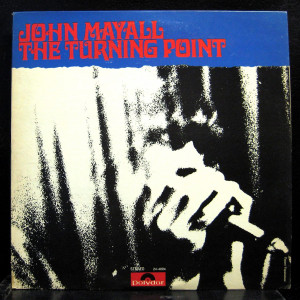

So when I saw this album, The Turning Point, in the record racks, I decided to give it a try. My first response (and I remember it very well) was, “You call this the blues!?!” It is 30 years on. My knowledge of what is and what isn’t “the blues” no longer depends on measuring everything against one Muddy Waters album (although that is still a standard worth keeping in mind); so when I saw this Mayall album again, I was very excited and couldn’t wait to see how it measured up!

Mayall’s original liner notes say, “the time is right for a new direction in blues music. Having decided to dispense with heavy lead guitar and drums, usually a ‘must’ for blues groups today, I set about forming a new band which would be able to explore seldom-used areas within the framework of low volume music …” Hmmm. The band had only been together for four weeks when this album was recorded at the Fillmore East Theater in New York.

Thirty years later, blues music has gone through many more phases. Right now we hear more blues than ever before. It shows up in beer commercials and film soundtracks. It is sampled and rapped over. And the legends of blues are being remastered and reissued for a new generation. John Mayall’s brave experiment sounds better than ever.

Led by his own vocals and harmonica work, this combo featured the acoustic finger-style guitar of Jon Mark, Steve Thompson on bass, and Johnny Almond on saxes and flute. The music is quiet, intimate and engaging. Mayall has never been a strong vocalist. He is no blues shouter but adopts a more Robert Johnson-like approach here. His reedy voice rides on top of the instrumentation as he sings about politics, homesickness and “love without entanglement.”

Jon Mark had been a British session guitarist before joining Mayall. He had co-produced Marianne Faithfull’s early albums with Mick Jagger and accompanied her on the road. He also toured as a folky duet with Alun Davies (guitarist for Cat Stevens). His acoustic guitar playing is brilliant. Perhaps because it is buried a bit in the mix, you find yourself listening for it, hoping to catch a glimpse of Mark’s folky string work as it weaves in and out of the ensemble. Saxophonist/flutist Johnny Almond had been in Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band and the Alan Price Set, playing jazz-influenced rock when Mayall hired him.

He is the star of The Turning Point. Whether on tenor or alto sax, or playing the flute his is the lead voice. This was a major change for British blues in the ’60s. The focus had always been the lead guitar, loud and stinging, leading to the hero worship of icons like Green, Clapton, Mick Taylor and others; but the warmth and humanity of the woodwinds as played by Almond looks back to Johnny Hodges in the great Ellington bands.

Steve Thompson has the job of holding this all together. With no drummer, it is incumbent on the bass player to provide a solid foundation, and Thompson does this extraordinarily well. He maintains the beat and provides the framework upon which Almond and Mark can hang their improvisations. Then Mayall punctuates the ensemble playing with his vocals and masterful blues harp. Mayall also fills out the sound with a slide guitar, a little telecaster and some tambourine.

The songs are basic blues structures with lyrics by Mayall. The keys are listed; as testament to the completeness of Mayall’s harmonica collection they range from E to D-flat. Mayall describes each song with one sentence on the liner. “The Laws Must Change” is “a few personal observations of police vs. youth and the drug situation” in C; “Saw Mill Gulch Road” is “the story of an innocent encounter one night in Monterey, California” in E and so on. The former is a bopping harp-driven shuffle, the latter a haunting flute-accompanied ballad, with spooky slide guitar in the background. The highlight, though, is the last song in the set. “Room To Move” rocks out (in D-flat), Mark’s guitar higher in the mix, Mayall trading vocals and harp, and Almond foregoing the saxes for some mouth percussion. You’ve never heard a “drum” solo like this!

Often our memories play tricks on us. Movies that we loved when we first saw them seem silly and clumsy when we watch them again. Songs that meant something in high school mean nothing as we grow older. John Mayall’s The Turning Point is not like that. It is even stronger after 30 years.

(Polydor, 1969; CD reissue, 2000)