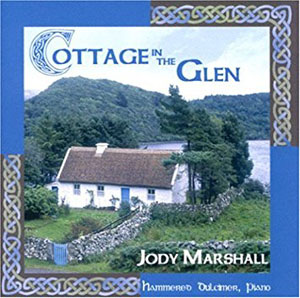

Jody Marshall has a distinct facility for drawing together a variety of musical threads into a rich and engaging weave. Cottage in the Glen was my introduction to her music, and I enjoyed it thoroughly.

Jody Marshall has a distinct facility for drawing together a variety of musical threads into a rich and engaging weave. Cottage in the Glen was my introduction to her music, and I enjoyed it thoroughly.

One hallmark of this collection is the astonishingly fluent musicianship: flawless performances by all hands, who include not only Marshall on hammered dulcimer and piano, but singer Grace Griffith and a full complement of guest artists.

Needless to say, it all has a Celtic flavor. “Mrs. Anne McDermott Rowe” is a tune that comes from the Irish harper Turlough O’Carolan, active sometime before 1800, that Marshall has deftly transposed to the hammered dulcimer. The opening track, on the other hand, begins with Marshall’s own song, “Three Sisters,” which segues into Duane Allman’s “Little Martha,” performed on hammered dulcimer and percussion, and moves immediately into Fernando Largo’s “Cau’l Chouzano,” a tune from Asturias in Spain, where the Celtic legacy is still strong; it’s a lovely ballad, with dulcimer, harp, flute and fiddle blending together seamlessly. Dulcimer and guitar take on eighteenth-century composer Adam Falckenhagen’s “Vivace,” which is rather less energetic than its title might lead you to suspect, at least in this rendering, but engaging, nevertheless.

The hammered dulcimer (or “hammer dulcimer,” as he refers to it) in the hands of Malcolm Dalglish becomes something very different. Jogging the Memory is a collection of Dalglish’s own compositions, the end result of a process of exploration, finding the sounds the dulcimer can make and making music from that. It is, really, a journey in sound (in other words, new age music of the best sort) that draws on Dalglish’s experience in theater and as a storyteller as well as musical influences at least as diverse as anyone else’s — Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, Zap Mama. Sweet Honey in the Rock, the Beatles.

The hammered dulcimer (or “hammer dulcimer,” as he refers to it) in the hands of Malcolm Dalglish becomes something very different. Jogging the Memory is a collection of Dalglish’s own compositions, the end result of a process of exploration, finding the sounds the dulcimer can make and making music from that. It is, really, a journey in sound (in other words, new age music of the best sort) that draws on Dalglish’s experience in theater and as a storyteller as well as musical influences at least as diverse as anyone else’s — Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, Zap Mama. Sweet Honey in the Rock, the Beatles.

It’s almost impossible to single out a track or three to use as examples: there is a fundamental unity to these compositions, and such a fluid progression from one to the next that it doesn’t really matter where the one stops and the next begins. Does it bear close listening? Yes, if for no other reason than the clarity of Dalglish’s playing. He likens the hammered dulcimer to a drum with a bright, sharp attack and a long and mysterious decay; his playing, then, is aimed toward achieving the balance point, the trade-offs between melody, harmony and rhythm that keep the mystery of that sustain without burying the clarity in a big sea of the remnants.

Dalglish likens his working method to finding constellations in the night sky. One might equally well use that as a description of the result.

(Maggie’s Music, 2005)

(Windham Hill Records, 1986)