This album and I go back a long way. Coming up on 50 years, actually. It was introduced to me by my Spanish teacher in the spring of 1974 during my freshman year at university, and at the time I had no idea that it was a brand new release. Joan’s 15th studio album, it was inspired by the military coup in Chile in September 1973 that overthrew Salvador Allende, and dedicated “to my father, who gave me my Latin name and whatever optimism about life I may claim to have.” It’s sung entirely in Spanish except for one song in Catalán and one with wordless vocals.

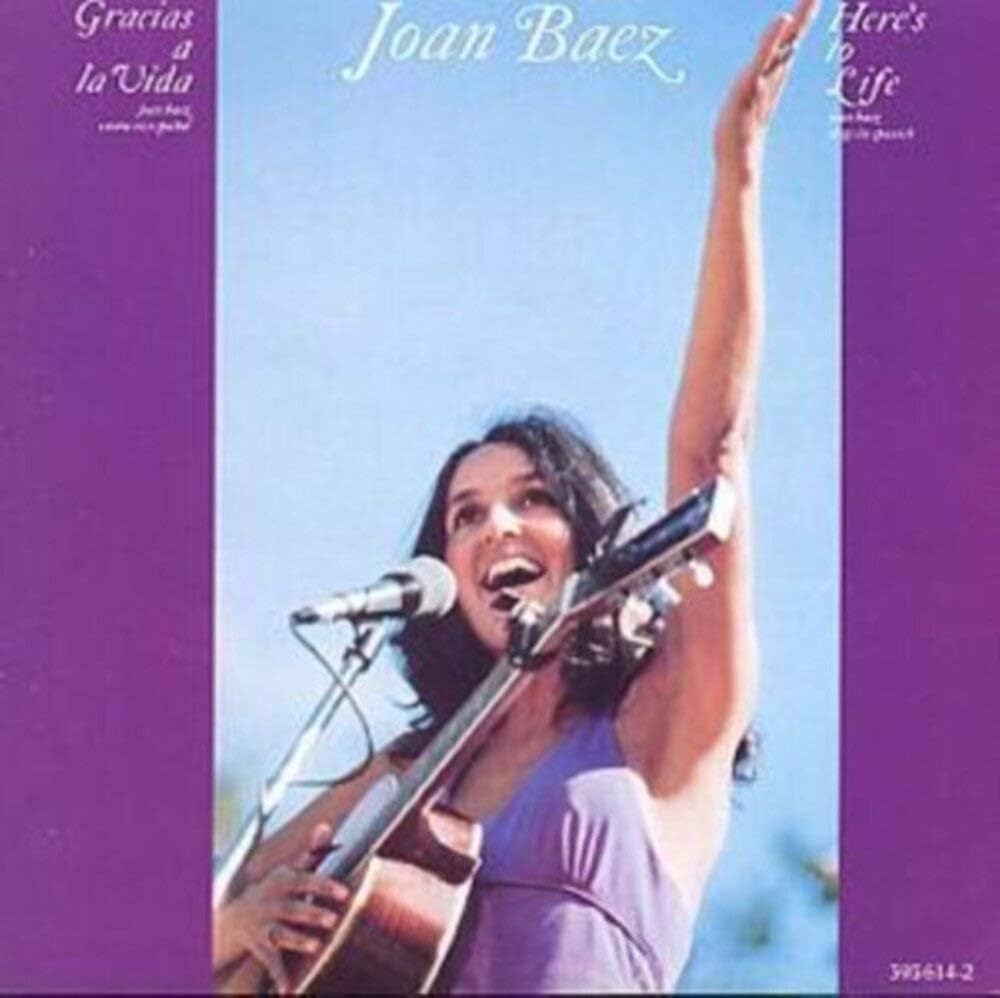

This album and I go back a long way. Coming up on 50 years, actually. It was introduced to me by my Spanish teacher in the spring of 1974 during my freshman year at university, and at the time I had no idea that it was a brand new release. Joan’s 15th studio album, it was inspired by the military coup in Chile in September 1973 that overthrew Salvador Allende, and dedicated “to my father, who gave me my Latin name and whatever optimism about life I may claim to have.” It’s sung entirely in Spanish except for one song in Catalán and one with wordless vocals.

I was familiar with the sad tale of Allende’s overthrow. Aside from being a news junkie from a young age, I’d been alerted to the extraordinary election of the socialist in Chile in late 1970 by my very first Spanish teacher, who had served in the Peace Corps in Ecuador. “Keep an eye on Chile,” he advised. “We’ll see how long the CIA allows Mr. Allende to remain in power.” Or words to that effect. So I was moved by the inclusion of the unbearably sad and romantic “Te Recuerdo Amanda” by Victor Jarra, one of the victims of the coup. The poet is remembering Amanda as she walked to the factory to meat her boyfriend Manuel, only to find that he and others had been slaughtered by soldiers.

Janie, the firebrand teaching assistant who led my class that academic year of 1973-74, played the whole album for us, and helped us suss out the meanings of the lyrics, giving us some background on the Latin American poets and composers who penned some of the songs – and giving context to the traditional ones.

There’s one song nearly every American of my generation knew, the Cuban folk song and Latin American anthem “Guantanamera.” It was a big hit single in the ’60s for The Sandpipers, who stole it … er, borrowed it from The Weavers. I like Joan’s version best. There are some other folk songs both traditional and modern on Gracias. There’s the Mexican traditional “La Llorona,” (The Weeping Woman), a massively lengthy song from which Joan culled a few very effective verses. And the delightful “De Colores” (In Colors), a lively ditty known all over the Spanish speaking world. I understand that it was one that Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers appropriated for their marches and rallies. It’s very fun to sing, especially the final verse about the different sounds made by the rooster, the hen and the baby chicks. Then at the end is a Spanish translation of “We Shall Not Be Moved,” which segues into the poem “Guerilla Warrior’s Serenade,” which Baez recites. I’ve always thought it an interesting example of the way translations often differ from the original, that this Spanish version’s title and refrain, “No Nos Moverán,” literally means “they will not move us,” rather than the English “We will not be moved.” Baez also sings/recites another traditional piece, “Paso Rio” (I Pass A River) that is full of symbolic pastoral language.

Some of the moving modern songs (often connected with social movements) include the Spanish “Llegó Con Tres Heridas” (I Come With Three Wounds), a minimalist but moving love poem; the title song, Chilean Violeta Parra’s humanist hymn “Gracias a la Vida,” upbeat and stirring as the opening track. The traditional Catalan song “El Rossinyol” (The Nightingale) is beautiful and one of my favorites even though I don’t understand the words.

A mariachi band, billed on the cover as Mariachi Uclatlan, backs Baez on two songs, the modern Mexican folk song “Cucurrucucú Paloma,” and the macho, romantic “El Preso Numero Nueve” (Prisoner Number Nine) in which the titular guy refuses to repent to the priest before his execution for killing his lover and his best friend, whom he caught in flagrante; instead he vows to hunt them even in the next life.

Baez wrote two of the album’s songs. The first, “Dida,” ends Side One. It’s a lovely tune, the only lyric being the title, repeated melodically as Joni Mitchell provides some soaring backing vocals. The second is probably my favorite Joan Baez recording and for my money one of her two or three best songs. “Las Madres Cansadas,” a translation of a song from her 1972 album Come From the Shadows where it appeared as “All the Weary Mothers of the Earth” is as relevant today as it was in 1974. It’s a stirring ballad of hope for all those weary mothers who labor in fields and homes, and who wait in distress for their husbands and sons to return from far-off jobs and battlefields, that someday people all over the world will rise up and shake off their shackles, refusing to work any more for the wealthy men or to fight for the generals. Fifty years on, I still sing along with this every time, and every time I cry. For some reason, the English language version never affects me that way.

Gracias A La Vida is a surprisingly coherent and well produced and recorded album for the haste in which it was put together. The musicians include members of L.A.’s famed “Wrecking Crew,” Tommy Tedesco on guitars, Milt Holland on drums, and Tom Scott on horns. Her very next album Diamonds and Rust was among her best and most popular, rising to No. 11 on the Billboard chart in the U.S. Gracias was kind of a curiosity in the U.S. but quite popular in Latin America. Its heartfelt renditions of classic songs presented in unfussy arrangements make it stand out as one from the era that still sounds quite good today. Give this one a listen, and spare a thought for all the weary mothers of the world.

(A&M, 1974)