I have been interested in the traditional music of the British Isles for more than 35 years and have grown older listening to the work of musicians who were already well known to the folk music loving minority when I first sat up and began to take notice of this rich field. I have watched contemporaries of mine, more talented than myself, who came under the spell of these older keepers of the tradition and then went on to develop their ability to sing the old songs and to improve their instrumental skills in playing the old tunes. I have seen them broaden their repertoire as they discovered new traditional material and perhaps newer compositions — their own or other people’s — that suited their style.

I have been interested in the traditional music of the British Isles for more than 35 years and have grown older listening to the work of musicians who were already well known to the folk music loving minority when I first sat up and began to take notice of this rich field. I have watched contemporaries of mine, more talented than myself, who came under the spell of these older keepers of the tradition and then went on to develop their ability to sing the old songs and to improve their instrumental skills in playing the old tunes. I have seen them broaden their repertoire as they discovered new traditional material and perhaps newer compositions — their own or other people’s — that suited their style.

When you have lived through this long process, you sometimes find yourself wondering, old-fogy-like, whether interest in this music is condemned to an inevitable decline. We have lost so many of the traditional singers and musicians, as well as the great revivalists and interpreters who learned from them, such as Bert Lloyd, Ewan MacColl and Peter Bellamy. There do not seem to be as many folk clubs and folk music pubs in Britain as there were in the past, and popular tastes have moved on from the days when bands like Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span were almost in the mainstream of popular music and sold to a wide public recordings of songs that had been around, in some cases, for centuries. Folk Roots magazine, Britain’s foremost “folk” publication, has changed its name to Froots and gives more and more attention to so-called world music, the further reaches of which include some increasingly bizarre collaborations and crossovers, not all of them convincing or successful. Minority musical interests receive very little attention from the broadcast media and the prospect of even a short radio or television program of interest to lovers of traditional music is enough to launch a thousand e-mails alerting the folk community to the date and time, as well as another thousand asking who can record it for those who will miss it.

However, every so often something hits me — smack! — in the ears that reminds me that this is no time to despair. The tradition may no longer attract the audiences that it did in the late Sixties and early Seventies, but I have recently been listening to a whole new generation of young musicians, men and women in their twenties, enthusiastic for the old music and determined to keep it alive — and even kicking. Sometimes one can see where the interest came from; if musicians like Eliza Carthy and Benjie Kirkpatrick are playing, in their own ways, innovative music strongly rooted in the tradition taken up and carried forward by their parents, this represents an encouraging sign of continuity. Kate Rusby, another twenty-something, has recounted how she absorbed folk music by travelling around with her parents while her father worked as a sound engineer at music festivals up and down Britain, and her two solo CDs are immensely mature and full of promise for the future. There are also young musicians such as Sharon Shannon in Ireland and more recently Tim Van Eyken in England who have similarly emerged as significant upholders of musical traditions that they are not afraid to stretch a little in new directions.

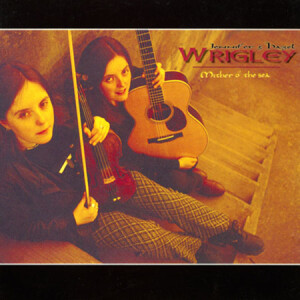

The Wrigley twins, Jennifer and Hazel, are also members of this new generation born in the final quarter of the twentieth century. They come from the Orkney Islands that lie off the northeast coast of Scotland, on the way to Scandinavia. The geography and history alone are enough to guarantee a fusion of Celtic and Nordic musical traditions, although the latter influence is possibly a little more Scottish in flavour in Orkney than in the Shetland Islands further to the northeast, which are very Nordic in character. However, like so many young musicians today, the Wrigley sisters have opened their ears to music from a variety of traditions, although I hasten to add (in case it seems that I’m contradicting my comments regarding Froots) that none of the exotic influences is so far removed from Orkney as to seem outlandish or merely trendy. You simply know that they must have listened to Irish, American, Quebecois and Cape Breton music as well as to their Scottish, Shetland and Nordic neighbours.

Most of the pieces played on this all-instrumental CD are composed by the sisters themselves (nearly always by Jennifer) or by other Orkney musicians, and respect local traditional forms. A couple come from mainland Scotland (not to be confused with Mainland in Orkney). To my surprise, a perusal of the booklet revealed that only the very last of the 23 tunes spread over 12 tracks is a traditional piece, a jig from Holm (a Nordic word that simply means “island”). Yet a listener could be forgiven for supposing that almost every piece is “trad. Arr. Wrigley,” so close do they stay to the tradition. I would except from this generalization Jennifer’s “Adelaide” and “The Phantom Flight,” which together make up track 7, composed in Australia in a bout of homesickness. They are exceedingly beautiful tunes, played in a fairly traditional style but nonetheless noticeably modern in feel.

Jennifer Wrigley is a fiddler, and her masterly bowing is heard on every cut. She is confident enough to introduce musical allusions to the various styles of fiddling that she has absorbed without ever losing the essential unity of the Orkney tradition. On one track (a tune with the unusual but precise title of “Compliments to the Orkney-Norway Friendship Association” coupled with “The Mester Ship”), she takes up the hardanger fiddle, or hardingfele, an instrument used in the impressive fiddling tradition of Norway. Its particular characteristic is that in addition to the four normally stopped and bowed strings, it has up to four additional strings that resonate in sympathy with the actively played ones and create a drone effect.

Sister Hazel accompanies the fiddling on guitar or piano and provides an intuitively appropriate counterpoint to her sister’s violin. Purists can argue until kingdom come about whether the guitar, and even more the piano, are appropriate instruments in this particular musical tradition. In this case, Hazel’s backing complements Jennifer’s fiddle-playing so perfectly that it would be churlish to quibble. I therefore decided to picture in my mind’s eye a village hall on a wind- and rain-swept island in Orkney where Hazel sits in a corner, occasionally turning from the keyboard to the guitar and vice-versa, while the other musicians play along and the local people dance to the jigs, reels, polkas and waltzes, which together with the occasional march or air, make up the CD. The other musicians, incidentally, are Aaron Jones (bass guitar), Eamonn Coyne (banjo and mandolin), Kevin Macrae (cello), Rick Bamford (percussion) and Simon Thoumire (concertina and whistle). I am not familiar with most of these musicians, but Simon is another up-and-coming young musician to watch.

In a review in Green Man Review of Roy Harris’s Live at the Lion CD recorded at the White Lion Folk Club, I paid tribute to a number of small record companies that valiantly keep alive the best in folk, traditional and acoustic music in an increasingly cutthroat world (recent news of a merger bringing Warner and EMI under one roof seems to threaten us with even less choice of music from mainstream sources in future). I knew when I wrote out my list that it was illustrative rather than exhaustive and that I would be kicking myself shortly for omitting some other “small big hitters.” The Wrigleys’ recording is on the Greentrax label and this company is another to which we owe undying gratitude for its resolute championing of traditional and similar music. This is a CD that will appeal to anyone who enjoys good fiddling with its feet firmly rooted in the legacy of the tradition and its eyes set just as firmly on the horizons of both space and time.

(Greentrax, 1999)