Craig Clarke contributed this review.

Craig Clarke contributed this review.

Music legend Isaac Hayes began his career as a session musician and songwriter for Stax Records. (He and partner David Porter wrote “Soul Man” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’ ” for Sam and Dave.) Hayes’s debut solo album Presenting Isaac Hayes was a flop, however, and he was intending to go back behind the scenes when Stax severed its relationship with Atlantic Records in 1968. This resulted in Stax’s losing its entire back catalog.

Executive Vice President Al Bell (also a songwriter and producer) thought quickly and initiated extensive recording sessions with all of Stax’s house artists, in order to create a new “back catalog” of 27 albums by mid-1969. Hayes agreed to record this second album in exchange for creative control, though Bell would still sign on as producer.

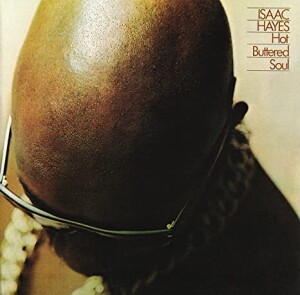

The result was Hot Buttered Soul, a four-song, 45-minute exercise in interpretation and improvisation that still astounds and mesmerizes to this day. I believe that the album’s long-lasting reputation lies in its sound; it was ahead of time then, and modern artists still aspire to its originality. The multilayered music feels timeless, presenting a symphony of love gone sour.

If you consider the traditional four-movement format as perfected by Haydn and his students Mozart and Beethoven, this becomes clearer. In the opening track, the singer asks his former love to “Walk on By” so she won’t see him crying. Hayes’s interpretation of the Burt Bacharach/Hal David pop standard (popularized by Dionne Warwick in 1964) serves as the introductory movement, laying out the main ideas behind Hot Buttered Soul: the thickly orchestrated (strings by the Detroit Symphony), lengthy interpretation — 12 minutes, in this case — of someone else’s music. (The process of taking a popular song and expanding on it harkens back to the symphony as well, since composers often used their local folk music as the springboard for their works.)

“Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic” (which has been inconsistently misspelled since its conception, even on the album cover — the backup singers are clearly saying “-nistic”) is the fun and light second movement. Its lyrics, by Hayes and Bell, refer to the practice of using big words unnecessarily, and take a more active approach with an attempt at re-wooing the lost love through high-minded compliments: “Your modus operandi is really all right, out of sight. / Your sweet phalanges really know how to squeeze. / My gastronomical stupensity is really satisfied when you’re loving me.” (Although some doubt is laid on the singer’s own knowledge since the chorus is, “Now tell me what I said.”)

But the main attraction, other than trying to decipher the lyrics, is the instrumental that fills out the latter six minutes of the song’s nine-minute running time. Pianist Marvell Thomas spans the range of keys while the Bar-Kays’ bassist James Alexander and drummer Willie Hall (who would later join The Blues Brothers Band) lay down a groove that hits somewhere around the coccyx and requires the hips to move in time.

While “One Woman” is not a minuet, or even in 3/4 time, it does serve as the “dance” on this album. The shortest song by far at only five minutes (and surprisingly never a contender for a single), its lyrics about what Mary McGregor called being “torn between two lovers” only emphasize this role. Its chorus could not be clearer — “One woman’s making my home while the other one is making me do wrong” — though there’s obviously some communication lacking in the former relationship.

The closer, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” differs from the popular Glen Campbell recording of this Jimmy Webb song in practically every thinkable way. First off, Hayes holds a single chord on his organ and drummer Willie Hall clangs a single cymbal for eight minutes while Hayes expounds on the story behind the song. I’ve never heard anything like it. It was reportedly performed live numerous times before recording, and yet it seems entirely extemporaneous. For the remaining 10 minutes, Hayes draws out every single drop of emotion that can be squeezed from these powerful lyrics, turning it into a most-grand finale of this “symphonic” soul classic.

Stax has rereleased the album with liner notes by Jim James of the band My Morning Jacket (fan) and Bill Dahl (historian), digital remastering, and two bonus tracks: the single edits of “Walk on By” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” The sound is remarkably clearer than my previous recording of Hot Buttered Soul, and that will be the main draw for repurchasers. The singles are novelties at best, with their only attraction being to compare where things were cut to make the songs playable on singles-oriented radio. Since the lyrics are not what raise this album above the rest, and the singles make sure to focus on those to the detriment of the wonderful instrumentals, fans are unlikely to listen to these more than a couple of times each, though they may serve as relatively smooth introduction to newcomers.

(Stax, 1969/2009)