Hubert Laws’ In The Beginning is one of my favorite albums of all time, and has been since I first bought the double-LP set in 1976. I feel honored and a little intimidated to have the privilege of reviewing the remastered release of this CTI classic from Masterworks Jazz, part of its celebration of CTI’s 40th anniversary.

Hubert Laws’ In The Beginning is one of my favorite albums of all time, and has been since I first bought the double-LP set in 1976. I feel honored and a little intimidated to have the privilege of reviewing the remastered release of this CTI classic from Masterworks Jazz, part of its celebration of CTI’s 40th anniversary.

Born in 1939 in Houston, Texas, Laws began playing flute in school. Several of his siblings also became musicians, notably tenor saxophonist Ronnie Laws, with whom Hubert made many recordings. He went on to become one of the top jazz flutists of his era, and also mastered the art of classical flute. He played on many pop, rock and rhythm ‘n’ blues records in the 1960s and 1970s, and he continues to play today at the age of 71. In 2010 he received a lifetime achievement award in jazz from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Laws had released several recordings under his own name (and guested on many more) when he made In The Beginning over four days in the studio in early 1974. It earned him a nomination for best jazz performance as a soloist that year, one of three nominations he has received. In The Beginning remains one of his most popular and durable recordings, combining several different styles of jazz, gospel and classical music.

Part of the recording’s magic surely has to do with the sterling production of label-owner Creed Taylor and engineer Rudy Van Gelder. And much credit goes to the crew of sidemen assembled for the sessions in February 1974 in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, starting with the core of Ron Carter on bass, Steve Gadd on drums, Dave Friedman on vibraphone and Gene Bertoncini on guitar. Carter hardly needs introduction — he has played with everybody who is anybody in jazz since he started playing professionally in about 1960, is one of the most-recorded musicians in jazz, and has taught at the highest university level for more than 20 years. Gadd was already well on his way to an influential career when he played on this record, and went on to become the highest-paid session drummer in the country. Friedman is one of the most innovative and influential vibraphonists of the era, and continues to play and teach from his home base in Berlin. Bertoncini is one of the best-liked guitarists in jazz, and has been influential in synthesizing American jazz with Brazilian styles.

Other musicians include Ronnnie Laws on sax and four keyboardists, led by the CTI house player Bob James.

But of course it’s Hubert Laws’ record, and he shines. In all my years of listening to this album, I’ve never detected a single note of his that doesn’t do exactly what it is meant to do. Laws plays with a rare combination of precision and warmth, logic and passion, and always in the service of the song.

The pieces that make up In The Beginning are all covers except one Laws composition, including some by big names like Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. Laws opens the album, though, with two selections by jazzmen who were not such public figures but were well-known and highly respected in the jazz world. First is the title track “In The Beginning” by Clare Fischer, who arranged it and plays electric piano on this piece and piano on the closing track. Fischer was one of the pioneers of the electric piano in jazz, but was best known as an arranger and composer. A university-level teacher of composition and improvisation, Fischer continued to work as a band leader well into the 21st century when he was in his late 70s. This piece opens with a statement of the theme in 5/4 (shades of Dave Brubeck’s influence), followed by a freeform section that draws on free jazz, modern jazz and modernist classical styles, and goes on through several more sections in different styles.

The second is “Restoration” by Harold Blanchard, a former missionary and minister who played and taught jazz until his death in 2010. This is a straight romantic ballad with a lovely melody, played mostly by a quintet comprising vibes, piano, drums and bass in addition to flute. Gadd’s drumming really stands out. Bertoncini’s electric guitar amazingly doubles Laws on the melody near the end, and the piece goes out with some playful counterpoint between the flute and vibes.

Up next, opening the original album’s second side, is a “classical” work, the popular and beautiful “Gymnopedie #1” by French proto-modernist and dadaist Erik Satie. In keeping with the composer’s ethos, Bob James’s arrangement is minimalist, with Laws backed by a string trio, piano, bass and guitar. There’s occasional doubling by Laws on flute and a few notes on electric piano in the improvised development section, during which Laws soars and flutters, birdlike, his control and clear tones impressive.

My younger self bought this album because of the presence of “Gymnopedie,” which I’ve liked since I first heard Dick Halligan’s Grammy-winning arrangement of it on Blood, Sweat & Tears’ self-titled second album. And it was probably the first track I listened to on In The Beginning. If that’s so, then the second would have been “Come Ye Disconsolate.” After the final solemn minor chord of Satie’s tune fades out, we’re treated to a balm of hope and joy as Bob James begins the piece with a big, warm major piano chord. “Disconsolate” is an old Methodist hymn, here rearranged (by James and Laws) in a stately waltz time. Backed by a simple ensemble of drums, bass, piano and joined by Richard Tee on sanctified organ, Laws takes this beautiful melody and plays it. At the end of the first chorus, he starts doubling himself on a baritone flute, and the proceedings rise to a slight climax, with the help of some judiciously exhuberant ride-cymbal crashes from Mr. Gadd. The vibes join in for an upbeat improv chorus and Laws’s two flutes twine around each other once again at the turn. The third chorus rises even higher, with everyone in impeccable control but so full of restrained passion that you just want to shout hallelujah! A brief but wonderful half-chorus coda brings the whole thing to a majestic close, the bass and organ fading out last. In 35 years of listening to this piece of music, I have never tired of it, and I hope somebody will play it really loud on a good system at my funeral.

After that breathtaking moment of spiritual uplift, Laws and Gadd launch — BAM! — into Sonny Rollins’s tightly-wound bebop standard “Airegin.” (That’s “Nigeria” backwards.) It’s five-and-a-half minutes of rapid double-beats on the kick-drum, quick slaps and rolls on brushed snare and ride cymbal, and Laws’ flute and piccolo running up, down and sideways with the mercurial melody and his improvisations on it. It’s one of those workouts that has become the measure of both drummer and instrumentalist (and even vocal ensembles including Manhattan Transfer and Lambert, Hendricks & Ross), and Laws takes second chair to nobody on it. And Gadd’s work … my goodness! It took me a long time to warm up to this piece, but nowadays I often catch myself whistling snatches of the tune … or trying to, anyway.

That ends the second side of the first platter in this original two-disc set, and if things never quite reach the heights of this side’s three disparate tracks, neither was the wax wasted on the second disc. In fact, John Coltrane’s brilliant and catchy “Moment’s Notice,” which comes next, is utterly charming. Great melody, finger-snapping rhythm, and Laws shows some impressive improv chops, with Gadd and Carter and James (on electric piano) pushing him hard. Brother Ronnie steals the reins and keeps the thing from going off the rails in the chaotic third turnaround, James plays a long lead section, and then Hubert takes things even farther afield, goading his ensemble to great heights before finally recapping the melody and bringing it all back home. It’s great fun to listen to.

Things settle down a bit for Rodgers Grant’s mildly swinging “Reconciliation,” although at 10 minutes there’s plenty of time for Laws and Co. to explore. From the first, Carter’s bass is way out front, so you know you’ll be hearing plenty from him, and you do. Gadd’s brushwork is sublime, too. And James gives a class in electric piano in which you hear the big difference between it and its acoustic cousin — he plays it somewhere between piano and organ, and although I still prefer either of those, James makes an eloquent case.

Pianist, composer and arranger Grant wrote the title track of Laws’ previous album, Morning Star (CTI, 1973), and in addition to contributing the previous track, he plays piano on the closer, Laws’s own 15-minute samba-fusion “Mean Lene,” which took up the whole fourth side of the LP set. Everybody gets a chance to shine on this one, starting with Friedman on vibes, and percussionist Airto Moreira — who at the time was just coming into his own as one of the top percussionists in the Western Hemisphere — adds all kinds of color.

In The Beginning is quite a ride, and I think it easily transcends its time. It contains such a wide range of styles, all played seemingly effortlessly and with almost casual creativity by a world-class ensemble. I’ve heard a lot of the CTI albums, and I think this is easily one of the best, a tour-de-force that put Laws in his place in the jazz pantheon. If you like contemporary jazz or soul jazz, you need this album.

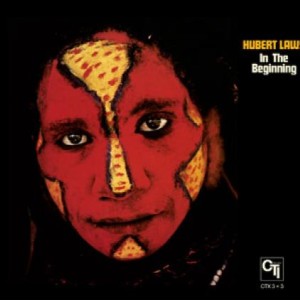

As with all of these remastered 40th Anniversary albums, this CD package is a replica of the original album, complete with front and back cover photos by the great Pete Turner (minus, unfortunately, the glossy stock it was originally printed on), the classy b&w portrait of Laws and clean liner notes inside. Well done.

(Masterworks Jazz, 2011; CTI 1974)