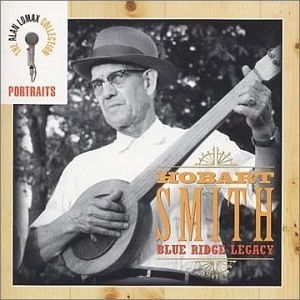

Dock Boggs got all the attention, but there were many other extraordinary musicians playing in the hills. Hobart Smith passed away in 1965. The world was just discovering the Beatles, there was no room for a mountain man on the radio at that time. He was a triple threat, well known as a banjo virtuoso; he could also handle himself extremely well on guitar and fiddle. His voice is an echo from the mountains where he lived. Hobart Smith was a major talent, and now the world is looking for this kind of naive folk music. The Alan Lomax Collection presents a cross section of Smith’s work, Blue Ridge Legacy.

Dock Boggs got all the attention, but there were many other extraordinary musicians playing in the hills. Hobart Smith passed away in 1965. The world was just discovering the Beatles, there was no room for a mountain man on the radio at that time. He was a triple threat, well known as a banjo virtuoso; he could also handle himself extremely well on guitar and fiddle. His voice is an echo from the mountains where he lived. Hobart Smith was a major talent, and now the world is looking for this kind of naive folk music. The Alan Lomax Collection presents a cross section of Smith’s work, Blue Ridge Legacy.

Smith’s early recordings (circa ’40s-’50s) inspired musicians like Mike Seeger and John Cohen to play early American music. He had played in minstrel shows in 1915 and dance parties throughout the Appalachians. He played at auctions, for society events and even in dance halls. “I made practically two-thirds of my living at music,” he is quoted as saying, but he never left the mountains.

The recordings released on Blue Ridge Legacy include the ’42 sessions, later sessions with Alan Lomax and some live recordings from 1963. It is a true portrait of a life spent in music.

The album begins with a fiddle tune, “The Devil’s Dream.” Hobart Smith shows his ability with a fiddle immediately, and also with the second cut, “Drunken Hiccups,” which also features his vocals. The second track is the song better known as “Rye Whiskey” with the novelty added of a hiccupping violin!

Then Hobart’s banjo playing comes to the fore. The previously unreleased track, “The Cuckoo Bird,” from 1942, is a virtuosic tour de force. A page of tab is included for this tune. “Banging Breakdown” is a buckdance from 1946, with an uneven tempo yet a rhythm that is danceable. In all the banjo tunes Smith’s ability is clear. Rapid-fire runs and rolls, a strong sense of tempo, and a head for melody highlight his playing.

“Railroad Bill” is a song played on guitar which evokes the melody and theme of Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train.” Smith’s vocals are countrified but more melodic than those of Dock Boggs. Boggs might have had a slight advantage on the banjo, but Smith more than makes up for it with his ability on the guitar and fiddle.

Hobart also played the piano. His abilities at the 88 keys are limited but interesting. His left thumb lays down a syncopated bass while his right hand picks out the melody. His piano playing is reminiscent of his guitar style. “Sourwood Mountain” blends seamlessly into “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad” … in fact I was listening to the second verse of “Going Down the Road … ” before I noticed that the track had changed.

Banjo and guitar tunes are where Smith shines, and this disc is rich with them. “Pateroller” and “Chinguipin Pie” both highlight the banjo, while also including some recorded comments by Smith. He is an interesting raconteur. One late surprise is the inclusion of a tune called “Unidentified Electric Guitar Tune,” which translates Smith’s style very well to the electric guitar.

For people interested in the development of American music, traditional folk songs and singers, or just plain good playin’ an’ pickin’, Blue Ridge Legacy provides far more than a simple history lesson.

(Rounder, 2001)