The idea of “meaning” in music is a complex one, the pursuit of which can go all sorts of places I don’t want to go right now. Suffice it to say that most commentators feel that relating music to some sort of narrative line is sufficient to address the question, and I, at this point at least, am not going to argue against that approach. This leads naturally to discussions of “program” music, which is something we find reflected in everything from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to movie soundtracks, stopping along the way to encompass such diverse works as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 and Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, not to mention opera and ballet in general.

Hector Berlioz was one of the great creators of program music in the nineteenth century, with such works as Harold in Italy and Roméo et Juliette to his credit, not to mention that perennial favorite, the Symphonie Fantastique.

Hector Berlioz was one of the great creators of program music in the nineteenth century, with such works as Harold in Italy and Roméo et Juliette to his credit, not to mention that perennial favorite, the Symphonie Fantastique.

Initially titled Episode in the Life of an Artist, the Symphonie Fantastique is supposed to reflect Berlioz’ courtship of the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, whom he had seen in the roles of Juliet and Ophelia in the first performances of Shakespeare in Paris. It was also meant to be heard with its pendant Lélio, and Berlioz eventually expressed the wish that the program not be published with performances of the Symphonie if it was performed alone. Volumes have been written about the symphony and its program, particularly emphasizing the autobiographical quality of the work. It seems to me that autobiographical references should be taken with a grain of salt: Berlioz, like many of his peers in the nineteenth century, was attracted to the fantastic, but it’s likely that his familiarity with opium (supposedly the context of the last two movements) and witches’ Sabbaths was derived from literary references rather than real life.

That said, and all program aside, in addition to being one of the most popular works in the symphonic repertoire, the Symphonie Fantastique is one of the most engaging in purely musical terms. This is Berlioz in his essence: a composer of vast resources, inarguable genius, and iconoclastic temperament who nevertheless looked to Beethoven, that touchstone of nineteenth century musical respectability, as a forebear. I think that, even without knowing the “story” that underlies this work, one is easily captivated by the sheer brilliance of the music.

Roméo et Juliette presents a somewhat different case: certainly programmatic in its concept, it also moves into slightly different territory. Berlioz called it a “dramatic symphony,” and it can be easily linked to such later works as the tone poems of Richard Strauss and even, I think, the markedly autobiographical symphonies of Mahler. I find it ironic that the “Love Scene” included on this disc is so strongly reminiscent of the music of Richard Wagner: the two composers were not always cordial, and the respect each professed for the other’s music easily gave way to disdain. Call it Zeitgeist — this piece is as richly colored, fluidly lyrical, and intensely dramatic as anything performed at Bayreuth (or St. Petersburg, for that matter — there are passages that call to mind some of Tchaikovsky’s better moments).

As to the merits of this particular recording, I can’t think of many conductors of the twentieth century who had as much sympathy for the music of Berlioz as Charles Munch — the only real contender is Colin Davis, whose readings are often more astringent but no less intelligent.

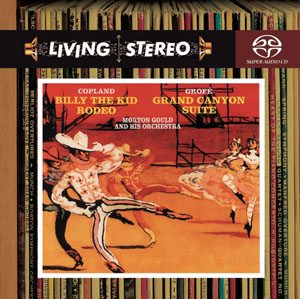

The idea of “program” is, of course, an obvious one when we look at Aaron Copland’s suite from his ballet Billy the Kid. Dance as high art, at least pre-Martha Graham, is more or less tied to a narrative, in this case the story of William Bonney, the desperado who has become a figure in America’s own mythology. Copland’s music not only reflects the folklore of Billy the Kid and the West itself, but also seems to encapsulate some deep impulses in the American psyche: the urge to push out, to explore, to tame the wilderness, and also the reverence for the majesty of nature and the playful innocence that are still important elements in the American experience. Put all this in the hands of one of the premiere exponents of American modernism in music — and one who had an affinity for American folk music — and you have an engaging and substantial work.

The idea of “program” is, of course, an obvious one when we look at Aaron Copland’s suite from his ballet Billy the Kid. Dance as high art, at least pre-Martha Graham, is more or less tied to a narrative, in this case the story of William Bonney, the desperado who has become a figure in America’s own mythology. Copland’s music not only reflects the folklore of Billy the Kid and the West itself, but also seems to encapsulate some deep impulses in the American psyche: the urge to push out, to explore, to tame the wilderness, and also the reverence for the majesty of nature and the playful innocence that are still important elements in the American experience. Put all this in the hands of one of the premiere exponents of American modernism in music — and one who had an affinity for American folk music — and you have an engaging and substantial work.

Rodeo, while using some of the same elements, is rather more light-hearted. There is less symbolism, and the story line is somewhat more standard: cowgirl wants cowboy, and cowgirl gets what she wants (although, as it turns out, the cowboy she wants is not the one we — or she — thought she wanted). Call it a romantic comedy, derived, perhaps, from the same sources as Billy the Kid, but with a much different aim. In spite of the difficulty of assigning “meaning” to music in and of itself, I can’t help but ascribe humor, wit, and a certain acerbic quality to Copland’s score in this one.

Fred Grofé’s Grand Canyon Suite is, without doubt, one of the great warhorses of the “light classics” circuit. It is also a prime example of the idea of musical portraits, another aspect of program music. In this case, the portrait is of one of the great natural wonders of the world. I don’t know if Grofé’s suite does it justice — that’s very much a subjective judgment — but he certainly managed to create a richly rewarding piece of music. It is, regrettably, one of those works that has gained a reputation as somehow not quite up to snuff, simply because it’s not perceived as “serious” in the same way that Beethoven or Berlioz are. It’s still wonderful, with the same range of mood and the same emphasis on orchestral color that one might find in Vaughan Williams or Respighi; perhaps a good comparison would be Smetana’s Ma Vlast: it has that same pastoral feel, with a full sense of the drama inherent in its subject.

Morton Gould is certainly no stranger to this music, and his intelligence and sensitivity as a conductor show through very well in this recording. He quite adeptly straddles the gulf in our minds between “serious” and “popular” and lets the music speak for itself, which is about the best one can ask for.

(Sony BMG Music Entertainment, 2006)

(Sony BMG Music Entertainment, 2006)