This CD is a collector’s item in two senses. First, it stems from the work of one of the most dedicated collectors of traditional music who ever lived. The sessions were recorded in London and in Norfolk, England during the fall of 1953 by Alan Lomax, whose youthful picture appears on the back of the enclosed booklet. He was assisted for these sessions by Peter Kennedy. Lomax was recording a disappearing breed of musicians in the British Isles, most of them elderly. He was perhaps the first one to systematically do such field recordings in Britain.

This CD is a collector’s item in two senses. First, it stems from the work of one of the most dedicated collectors of traditional music who ever lived. The sessions were recorded in London and in Norfolk, England during the fall of 1953 by Alan Lomax, whose youthful picture appears on the back of the enclosed booklet. He was assisted for these sessions by Peter Kennedy. Lomax was recording a disappearing breed of musicians in the British Isles, most of them elderly. He was perhaps the first one to systematically do such field recordings in Britain.

Second, this CD is clearly aimed at collectors. To ears more accustomed to studio recordings, to sophisticated musical arrangements, to the packaged words and music of Tin Pan Alley or even to the relatively polished work of today’s folk and folk rock singers and musicians, this is rough-hewn, down-to-earth stuff. It is not for the faint-hearted. And it could never be played as “background music” but requires close and unflagging attention.

Compared with most currently available recordings, listening to this CD is hard work. My teenage daughter came into the study while I was listening to the album and asked, “What’s wrong with his voice?” I was not surprised; she asks the same about Shirley Collins, who is almost a cocktail lounge singer compared with Cox. “What Will Become Of England” (or as Cox pronounces the word in the title track, “Eng-e-land” – almost identical to the pronunciation found in Holland, just across the North Sea from Cox’s native Norfolk) is composed of 19 more or less complete songs, five song fragments, 18 spoken pieces and four dance tunes, two of which are played on the melodeon (which Cox calls “a music”) and two more on a borrowed fiddle. If I describe the “non-fragments” as only more or less complete, it is because the extremely detailed notes often provide additional verses that Cox omits, taken from other singers’ versions of the songs.

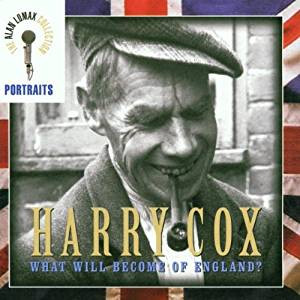

Harry Cox (1885-1971) sings the songs, always unaccompanied, plays the tunes, and reminisces about life in rural Norfolk – not only his own life but those of his father and grandfather. All of them were singers and entertainers in demand in pubs and at social gatherings, and all of them worked as farm laborers, although Cox’s father also went to sea, thereby extending the family’s repertoire of both songs and experiences. Cox is sometimes prompted by questions and comments from Lomax and Kennedy, but their presence is fairly unobtrusive; and Cox himself, his life, his work, his singing, his family and his opinions occupy center stage.

Some of the songs are well known. “The Spotted Cow” was popularized by Steeleye Span. Kennedy notes that Cox was scornful of those who performed traditional songs in this way, thus taking a different position from that of folk song revivalists such as Bert Lloyd, who encouraged innovative treatments of traditional songs, or Martin Carthy, Dave Swarbrick and John Kirkpatrick, who actually threw their lot in with the folk rockers. It is not clear when Cox made this comment. Presumably not in 1953, when the first generation of British folk rockers was barely alive. Had he actually heard real folk rock, or was he merely referring to the emasculated versions of folk songs that have always existed alongside the real thing? Whatever the truth, it is almost as if there was a religious code: singing is singing, instrumental music is instrumental, the two cannot be mixed. Cox’s instrumental playing is hardly virtuoso stuff, and as it is strictly segregated from his singing it is all the more exposed. However, at 68 years of age Cox could hold a tune and sing in key without any difficulty despite the lack of accompaniment.

Cox’s “Henry The Poacher” is a version of a widely collected song, pretty well identical to the version of “Van Diemen’s Land” recorded by Ewan MacColl, while his “Sweet William” is a close relation of “A Sailor’s Life” as performed by the early Fairport Convention, although the tune is different. Listeners familiar with the English traditional repertoire will probably also recognize “The Barley Straw,” “The Farmer’s Servant,” Charming And Delightful,” “Windy Old Weather,” “Young And Growing” (here sung in fragmentary form), “The Foggy Dew” and “Adieu To Old England,” even when they are variants of the best known versions.

Other songs are more obscure, some of them with a distinctly local flavor. “Barton Broad Babbing Ballad” is about the local way of catching eels, while “The Yarmouth Fisherman’s Song” reflects Cox’s father’s time at sea. I expected “Widdliecombe Fair” to be a version of the widely known Dartmoor song “Widecombe Fair” (the one about Tom Pearce’s gray mare), but in the event it is completely different.

The songs are interspersed with spoken texts, often included at a point where Cox’s reminiscences are relevant to the next song. As Kennedy’s notes point out, Cox speaks in a rich Norfolk dialect, whereas the songs are sung in something closer to standard English. This may be partly due to the fact that the songs were learnt from other singers or even from the printed sheets on which ballads were previously published, thus earning a degree of respect that puts Cox on his best linguistic behavior.

In some cases he seems to have been overawed by the printed texts. In “Henry The Poacher” there is a disconcertingly dyslexic reference to Warwick Goal in place of Gaol! In case potential listeners are worried about understanding Cox, it is not really difficult, partly because every word sung or spoken on this CD has been painstakingly transcribed and printed in the 40-page booklet, which also contains valuable background information. If I have any quibble with the notes it concerns Kennedy’s tendency to ascribe stronger politically and socially critical motives to Cox than I consider justified. Admittedly, there are a few references to poverty and class. I particularly like Cox’s quotation from an uncle: “I’ve seen more dinner times than I’ve had dinners!”

This CD is unlikely to sell like hot cakes, but it will appeal to the specialist public that is interested in hearing songs and reminiscences that reflect a way of life now vanished. It provides model versions of some songs that are still to be found in the repertoire of many musicians performing traditional English music, although they are often incomplete or slightly altered on this CD. In our own age, traditional performers like Harry Cox no longer exist to any significant degree in Britain or other “developed” countries, and so it is a logical corollary that folklorists of Alan Lomax’s kind have either given up collecting or have become ethnomusicologists obliged to visit increasingly remote locations to escape the influence of globalized popular music. Anyone who is interested in the sources and origins of English traditional music or of the vanished world in which such music flourished will find this CD a treasure house of original material.

(Rounder Records, 2000)