“How much more is there left to lose?”

“How much more is there left to lose?”

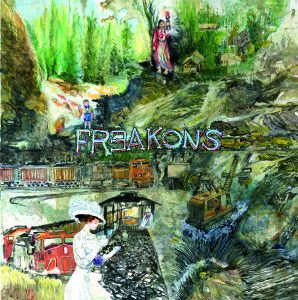

That’s a good summary of the spirit of this eponymous album, born of the fortuitous conjoining of two of the greatest underground bands on the globe – alt-country outliers Freakwater and U.K. punk cum Americana rabble rousers Mekons. If you’re spoiling for a good bit of pro-union, pro-worker, pro-environment musical mayhem, you’re in the right place with Freakons.

The Mekons, here represented by their two central figures, Welshman Jon Langford and Sally Timms, exploded out of the punk scene in Leeds in the ’70s, while Freakwater’s co-leaders Catherine Irwin and Janet Beveridge Bean hailed from Louisville, Kentucky. Wales, Leeds and Kentucky all are smack dab in the middle of coal country, which in both the U.K. and the U.S. have produced more than their fair share of hard-hitting music that reflects the lives of those who lived and died by coal. Mekons and Freakwater members ended up in Chicago’s alt-country scene (although Irwin remains in Louisville), making music that reflects the concerns and attitudes of the working class. Both bands and their many side projects and offshoots are the very definition of cult classics: they remain largely invisible to the public at large but are passionately adored by their fans.

The 12 songs on their eponymous album raise our consciousness, raise our ire, raise the hair on the back of our necks and hopefully get us to raise our voices and sing along. Freakons have been woodshedding them since at least 2017, playing them in Chicago at any rate until they got around to recording them.

My three favorites are Irwin’s masterful acoustic country chestnut called “Chestnut Blight,” Langford’s highly personal “Canaries” and another by Irwin, “Phoebe Snow.” I’m really pretty much a Catherine Irwin fanboy, I guess.

“Chestnut Blight” is consummate Freakwater material, a half-lilting, half-stomping ballad that highlights the ills suffered by the powerless at the hands of the powerful. Irwin sings the lead in her pugnacious alto full of dips and yips, while Bean’s strident soprano weaves harmonies around her. They’re augmented here by Langford, and fiddler/singer Anna Krippenstapel on the choruses and a melancholy fiddle line. The jaunty song runs through the calamaties that have befallen the trees and the land and the people of Appalachia since the arrival of Europeans: hills stripped of pines for ship masts, the death of millions of chestnut trees that once fed animals as well as people (both Indigenous and settlers), water that’s now “blacker than a lawyer’s ink,” the land ruined in the process of mining “and the miners left behind to pay the cost.”

“Canaries” is a simple but wrenching ballad, structured rather like a children’s song. The title of course is an allusion to the canaries that once were taken down into coal mines as a primitive air quality monitor – if the canary stopped singing and keeled over, that was your sign to get out quick. The point of the song being, if your young men are dying in the flower of their youth, you ought to be alarmed about it. In the introduction to the song during a gig at Chicago’s Hideout in 2017, Langford was incredulous that our then-President was talking about re-opening the mines: “I’m from South Wales and there’s no fucking person I know in South Wales wants to go down a coal mine.” Some men got out of fighting in World War I because they worked in the mines, the song notes, but it wasn’t necessarily a safe tradeoff, as the bridge verse says:

The best will choke in darkness both

On Flanders mud and slag

A pretty gift to put before

The Empire and the flag

Irwin’s scathing song “Phoebe Snow” is about a fictional character from an ad campaign devised by a railroad to persuade the public that the new anthracite coal was safer and cleaner than the old bituminous coal previously burned by the trains. This lily white woman was featured in print advertisements riding the train in her blindingly white dress, alongside her “testimonials” about how great train travel now was. You can read about it at the New York Historical Society’s website.

The song is a melodramatic fever dream that starts with Irwin chastising the coal mining states for allowing the rape of their lands and communities with the promise of clean coal (“Oh Kentucky, West Virginia, what was that fucking X you signed?”). After a screaming electric guitar solo from James Elkington and some uncredited wailing organ, it ends with a four-part dialog, Irwin, Bean, Langford and Timms all chanting different lines. Bean’s soprano wail of “so pure, so pure, so pure, so pure” floats atop the final cacophony. It’s over the top to be sure, but how can the response to mountaintop removal be mild?

That line I quoted at the beginning, “How much more is there left to lose?” is the final line from Langford’s “Abernant 84/85,” named for a coal mining village in Wales. The song first appeared on Mekons’ fourth album, 1985’s country-punk Fear and Whiskey which was reissued on CD in 2002 (and if I’m not mistaken came out on vinyl for a recent Record Store Day). It’s a bitter tale of a miner’s hard life, starting work at 17 years old and then ruined in his maturity by the mine’s closure. Langford and Timms share the lead on this one, he with his craggy baritone, she her pure folk singer’s soprano, a shambling old shantie in waltz time, the tune seeming to owe more than a little to the American folk ballad “Sweet Betsy From Pike.” And come to think of it, “Sweet Betsy” could well have started as a shanty. Bean’s wheezing melodica stands in handily for a concertina.

The connection, both spiritual and actual, of the coal miners on both sides of the Atlantic is the subject of the opening song, Langford’s “Dark Lords of the Mine,” spinning somehow off of a 1989 interview by talkshow host Dick Cavett with Welsh actor Richard Burton, himself a member of a coal mining family. It’s an offbeat number, which is not unusual for a Langford song, but features some great swinging harmonies from Timms, Irwin and Bean, and contributions from the other members of this troupe: Jean Cook and Anna Krippenstapel, who provide quasi-symphonic violin lines, and percussive electric guitar leads from Elkington.

There’s plenty more to go, too. “Judy Belle Thomson” is Bean’s ballad about a real woman who fought mountaintop removal in Appalachia. The bitter tirade about strike-breaking scabs, “Blackleg Miner,” sung here by Timms, is a splendid arrangement and performance, including harmonies from all. Similarly, Irwin sings lead on “Dreadful Memories,” a sarcastic rewrite of the hymn “Precious Memories.” Sarah Ogan Gunning, a Kentucky folk singer and union supporter during the Harlan County Coal War of the 30’s, wrote and sang it to highlight the suffering of coal workers and their families.

Similarly sarcastic is the lullaby “Coorie Doon,” by Scottish songwriter Matt McGinn, an influential figure in the UK folk revival of the 50s and 60s. Sally Timms’s haunting voice is perfect for the lead on this one, sung with a minimal acoustic guitar accompaniment and multi-part vocal harmonies.

Your daddy coories doon, my darling

Doon in a three foot seam

So you can coorie doon, my darling

Coorie doon and dream

Dead serious, though, is their cover, with Bean singing lead, of Hazel Dickens’s “The Mannington Mine Disaster,” the ballad of a deadly 1968 mine explosion. Both Mekons and Freakwater have long been fans of the music of Hazel Dickens both solo and with Alice Gerrard, and as the one-sheet says, “Learning about Hazel Dickens’s travels in Wales, and her work for solidarity between Welsh and Appalachian miners, was foundational to the Freakons.”

I’m kind of “meh” about “Never Thought I’d See The Day,” Langford and Timms’ country rock ballad about mine closure and repercussions; and also about the closer, “Blue Scars of a Miner,” Langford’s last-call tear-jerker that references Welsh popstar Tom Jones. Your mileage may vary though, and my goodness this album is top-heavy with powerful, hard-hitting songs. The combination of these two groups is magical: Langford’s gruff baritone and Irwin’s emotive alto are balanced to great effect by Timms’ and Bean’s sopranos, and everyone here has mastered the skill of playing tight but loose. Not only that, but thematically this album strikes a blow at the original fossil fuel that set us on our course of climate catastrophe, so it’s doubly timely. Freakons is the record we didn’t know we needed in 2022.

(Fluff and Gravy, 2022)