“Sui generis” is one of those terms that gets tossed around when discussing certain musicians. The Latin term means something like “of its own kind,” a fancy way of saying “unique.” But if it applies to anyone in American music in the past 100 years, then it certainly applies to Arthel “Doc” Watson. This new release by Smithsonian Folkways of the first known appearance of Watson as a headliner (or co-headliner) outside the rural South is proof enough.

“Sui generis” is one of those terms that gets tossed around when discussing certain musicians. The Latin term means something like “of its own kind,” a fancy way of saying “unique.” But if it applies to anyone in American music in the past 100 years, then it certainly applies to Arthel “Doc” Watson. This new release by Smithsonian Folkways of the first known appearance of Watson as a headliner (or co-headliner) outside the rural South is proof enough.

Watson, who died in 2012, became immensely popular during the American folk revival of the early 1960s, largely on the strength of performances like the one captured here. He was known for his acoustic guitar flat-picking prowess and his warm baritone singing voice, but when he was “discovered” by folklorist Ralph Rinzler he was playing rockabilly on the electric guitar around his North Carolina home. He also was proficient on clawhammer banjo, a tiny version of which was his first instrument, which he took up at a young age after going blind at the age of 2 years.

Back in 2001 Sugar Hill Records released a brilliant compilation of live performances Doc made at Gerdes Folk City in 1962 and ’63, his first solo live appearances on the folk circuit. He had laid the groundwork for those gigs with the shows he did in New York with fiddler Carlton, his neighbor and father-in-law.

As much as I love Doc Watson’s playing and singing, the appearance here of Gaither Carlton is equal in importance. I am a big fan of the highly embellished style of fiddling practiced in Cape Breton Island as well as Ireland and Scotland, and the man who made me a fan of the fiddle was the bluesy, swinging Vasser Clements. But the unadorned Appalachian style of the self-taught Gaither Carlton has a sturdy purity to it that brilliantly fits this music and complements Doc’s guitar picking. Musician and radio producer Stephanie Coleman says it quite well in the album’s superb liner notes:

To hear Gaither Carlton’s fiddling is to experience a personal, stately presentation of old-time music that is impossible to separate from the musician himself. Gaither’s playing is an extension of who he was as a person—modest and soft-spoken, with the quiet gravity of a lifelong farmer who spent most of his days close to home. Growing up without a radio or record player, he was fully a student of the aural tradition and learned songs and tunes from local and itinerant musicians.

Doc Watson, on the other hand, grew up with a radio and later a record player in his home, in addition to the traditional sources all around him. He was a tradition-rooted fusionist his whole career, as everyone who came to know him through the original Will The Circle Be Unbroken album (as I did) can attest. When you bring together two exceptional musicians who have slightly different takes on the music they have in common, that’s often a recipe for greatness. We see the beginnings of Doc’s greatness here.

This album is available on CD or as a double LP. Its 15 tracks consist entirely of traditional songs with the exception of the very first, “Double File,” a composition of Gaither’s. Some of these are quite ancient like “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” and at least one, “He’s Coming To Us Dead” originated around the time of the American Civil War, less than 100 years before this concert. A lot of them had knocked around the United States for decades or more, like “Corrina,” which came up through New Orleans and probably originated in the Caribbean. “The Dream Of The Miner’s Child” comes from an old English music hall ballad, while “Reuben’s Train” has an interesting pedigree – Doc learned it from his father, but a lot of his audience would have been familiar with it from the 1952 Folkways album *Anthology of American Music* edited by Harry Smith. Doc plays banjo and sings on this one as Gaither scratches out the tune’s deliberately high, screechy fiddle part, Doc interjecting at one point one of the kind of lines he became well known for, “Aw, fiddle it, son.”

I love that version of “Reuben’s Train,” and even more I love their “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” with Doc providing a two-note drone behind Gaither’s nimble playing, which includes both arco and pizzicato styles. Of course, every time I think I have a favorite, I hear something amazing in another song, like Doc’s Scruggs-style banjo picking and spot-0n singing on the sublime “Willie Moore,” accompanied by Gaither’s droning fiddle.

The recording is basically what we now think of as a bootleg. An 18-year-old banjo player named Peter Siegel with a new tape recorder got permission to record Watson and Carlton at New York University and, a week later, at Blind Lemon’s club in Greenwich Village. In the liner notes Siegel says in 2017 he started restoring, editing and mastering those tapes with an eye toward releasing them as an album. The sound is actually quite acceptable, much better than you’d expect from the age and provenance of the source tapes.

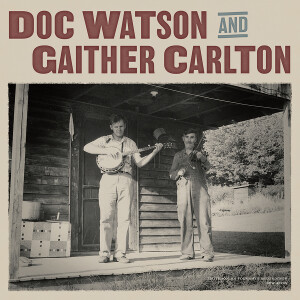

As always, Smithsonian Folkways has assembled a great package for this release. In addition to Siegel’s and Coleman’s notes there is an essay by Mary Katherine Aldin, who was nominated for a Grammy for her notes in the Muddy Waters Chess box set in 1990. The songs are well-annotated and there are several photos of Watson and Carlton from the period.

It goes without saying that all fans of Doc Watson will want this package.

(Smithsonian Folkways, 2020)