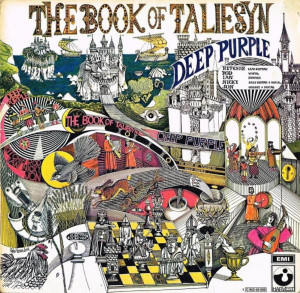

I’ve written in a few other reviews of classic albums about the influence my older brother had on … not exactly my taste, but the albums that I heard in the late 1960s and early ’70s. This album, the sophomore release by the very first version of Britain’s Deep Purple (what Wikipedia refers to as Mark I), is a good example. It has in common with many of them some great cover versions of other people’s songs. The first single off the album, a raucous cover of Neil Diamond’s “Kentucky Woman,” was a minor radio hit in North America, charting in the Top 40 in the U.S. and nearly making the Top 20 in Canada. I suspect that’s what drew my brother to the album, and we both liked Taliesyn so much that as soon as he found a copy of their debut Shades of Deep Purple he got it, too. It too had a great cover song by a favorite singer of ours, Joe South’s “Hush,” which had been this band’s biggest hit so far.

I’ve written in a few other reviews of classic albums about the influence my older brother had on … not exactly my taste, but the albums that I heard in the late 1960s and early ’70s. This album, the sophomore release by the very first version of Britain’s Deep Purple (what Wikipedia refers to as Mark I), is a good example. It has in common with many of them some great cover versions of other people’s songs. The first single off the album, a raucous cover of Neil Diamond’s “Kentucky Woman,” was a minor radio hit in North America, charting in the Top 40 in the U.S. and nearly making the Top 20 in Canada. I suspect that’s what drew my brother to the album, and we both liked Taliesyn so much that as soon as he found a copy of their debut Shades of Deep Purple he got it, too. It too had a great cover song by a favorite singer of ours, Joe South’s “Hush,” which had been this band’s biggest hit so far.

I’m not a huge fan of hard rock, but back then you took what radio served up, and what was in the zeitgeist. Everybody liked Iron Butterfly’s “Inna Gadda Da Vida,” and early Led Zepellin was gnarly. But I genuinely liked those first Deep Purple albums. They weren’t just mindless hard rock but a fusion of that with psychedelia plus what would go on to become prog rock and heavy metal. Keyboard player Jon Lord on his Hammond organ and other keys, plus his string arrangements and ability to mix classical elements with heavy rock, was the main architect of their sound. Add extraordinary guitarist Ritchie Blackmore to the mix, and you were in for some jaw-dropping fretwork in the form of extended solos plus duets and jams with Lord. Rounding out the lineup were Rod Evans on lead vocals, Nick Simper on bass and Ian Paice on drums, all quite good at their craft. Simper and Paice kept things cooking, and Evans had a versatile mid-range baritone, capable of singing purring ballads and roaring rockers alike.

The seven tracks on Taliesyn include four originals and three quality covers. In addition to their “Kentucky Woman” there’s a creditable take on The Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out” and a full-throated, bridge burning rendition of Ike & Tina Turner’s high “River Deep, Mountain High.” It’s tempting to say the best are those covers, but not so fast. The blues rock instrumental “Wring That Neck” features tons of that enthralling interplay between organ and guitar on a catchy melody, the rhythm section driving a deep groove (plus some explosive timpani in the intro and outro), and nifty solos on both organ and guitar. The band’s three-minute heavy prog intro to “We Can Work It Out” is a killer workout for Lord, and at one point Blackmore joins him for an impressive downward arpeggio in unison.

Then there’s “Anthem,” a tender love song that opens as an acoustic ballad, and really showcases Evans’s vocals plus the band’s ability to harmonize behind him. Lord takes a big Bach-influenced fugue of a break midway through (complete with string quartet), which this band nerd enjoyed back in the day — and it still works, I think. This track is second only to “Kentucky Woman” in Spotify streams from the album. The two weakest tracks are the opener “Listen, Learn, Read On,” and a similarly mystical ditty “The Shield.” “Listen, Learn,” from which the album gets its name in references to the Welsh tales of the Bard of King Arthur’s Court, has a four on the floor beat and production that’s treble heavy, with too-deep reverb on Evans’s vocals in an attempt to make the silly lyrics sound profound. “The Shield” at least lacks the excess reverb, but it never really gets off the ground either lyrically or musically. Album filler, except for Blackmore’s guitar solo.

But the band’s arrangements of the covers are not to be overlooked. In addition to that lengthy intro to the Beatles song, they totally turn Neil Diamond’s folksy bop into a guitar-driven rocker, Blackmore inventing a fuzzed-out lick and Evans throwing himself into the vocals. And the 10-minute “River Deep, Mountain High” that ends the album is a thing of wonder, from its “Also Sprach Zarathustra” intro to its driving finale.

Book of Taliesyn was definitely of its time, and this was not the version of Deep Purple that went on to mega-stardom with a string of hits that started with “Smoke On The Water.” But there are a lot of ideas here that were fresh at the time, some remarkable arrangements, a rhythm section capable of working a deep groove, and two extraordinary soloists in Lord and Blackmore. I don’t know whether I’d like it much if I heard it for the first time now, but it’s a romp down memory lane that those who were fans at the time don’t have to view as a guilty pleasure.

(Tetragrammaton, 1968)