David starts: The first we heard was that Sony was sending GMR the whole set. All fifteen of the recently remastered, hybrid super-audio Dylan albums, “for the ultimate audio experience.” They were advertising it this way…”You could never improve the MUSIC. But wait until you hear the SOUND.”

David starts: The first we heard was that Sony was sending GMR the whole set. All fifteen of the recently remastered, hybrid super-audio Dylan albums, “for the ultimate audio experience.” They were advertising it this way…”You could never improve the MUSIC. But wait until you hear the SOUND.”

The sound? Wait a minute…these are Bob Dylan albums! Dylan is well known for his quick, almost slap-dash approach to

recording. Spontaneity has long been more important to him than “the sound.” Working in a recording studio is not a thrill for Dylan, in fact he once described it like this, “Man, sometimes it seems I’ve spent half my life in a recording studio…It’s like living in a coal mine.” Having done some recording myself (and having once visited a coal mine) let me assure you…the air is slightly better in a studio. Nonetheless, we were excited about the prospect of receiving 15 Dylan albums, and Gary and I set out to divvy up the work.

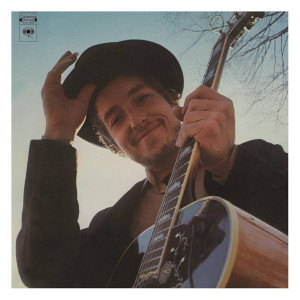

What arrived was a sampler selection. Three discs, maybe his best work ever, but only three of them. I quickly ran out and bought Nashville Skyline simply because it was a personal favourite. And I sat back to wonder, why they hadn’t included New Morning in their group of remasters. Then the discs arrived, and we hunkered down to listen to the new “enhanced” sound…to hear what all the shouting was about.

We’d like to do this in chronological order, but the fact is…it just seems appropriate to start with Nashville Skyline. After all, we’re not discussing Dylan’s development…we’re looking at the remastered versions of well known albums. Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan duet on “Girl From the North Country,” and you can hear every delightful syllable, every missed harmony, each botched line. It’s perfect. The album sounds open and vibrant. Like putting new strings on a guitar. It’s crystalline, and delicate…even when Bob and John are running roughshod over the lyrics. This new remastering makes clear the spontaneous nature of Dylan’s recording sessions. The Cash/Dylan sessions were supposed to result in a full blown album but it never appeared. (Bootlegs exist which show that first takes were the style of the day…and if “Girl…” was acceptable, so too was the rest…fascinating stuff.)

“Nashville Skyline Rag” was the first instrumental to grace a Dylan album, and on this new version the guitars of Norman Blake and Charlie Daniels, Kenny Buttrey’s drums, Charlie McCoy’s bass, and Pete Drake’s pedal steel are so warm that it feels like you’re right in the middle of the session. This was the second album to feature Dylan’s post-motorcycle accident vocals. No longer the scruffy Woody Guthrie wannabe, the kid had developed a chesty croon to sell these new country songs with. The hybrid Super Audio sound adds depth to the recording. This is a collection of Dylan’s new simpler lyrics. Simpler, in that they don’t contain the clever wordplay of the early folk albums; but more mature in that they deal with relationships, sweet and sour. “Lay Lady Lay,” “To Be Alone With You,” “I Threw It All Away,” and “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You.” “Throw my ticket out  the window,” indeed! Dylan displays a large dose of humour in “Country Pie,” and “Peggy Day.” A fine album, well served in the new format.

the window,” indeed! Dylan displays a large dose of humour in “Country Pie,” and “Peggy Day.” A fine album, well served in the new format.

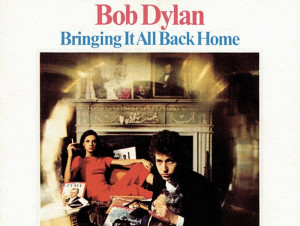

The year 1965 was a big one for Dylan. He shocked the folk world by playing electric at the Newport Folk Festival, and he released two of his most important (and, arguably, BEST) albums. Stephen Hunt reviewed the first of them for GMR in a marvelous article which you should all read . Bringing It All Back Home was the critical transitional album. Half acoustic, and half electric, it bridged the gap between folk and rock and prepared Dylan’s supporters for what was to come. Again, the remastering works wonders on this essentially simple recording. The songs are great. Models for folk-rock songs to come include “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” She Belongs to Me,” “Maggie’s Farm,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” and the benchmark “Mr. Tambourine Man.” This was the album where it all started for many of us. This is a new way to listen to it.

Dylan’s harmonica is subtle and beautiful on “She Belongs To Me,” but not as sweet as that electric guitar. Is it Bruce Langhorne? The liner notes tell you little. Just that Tom Wilson produced it, and Daniel Kramer took the pictures.

An insert contains the words of the poem that appeared on the back cover of the vinyl release. The poem is typical Dylan, obscure and dense. “i accept chaos. i am not sure whether it accepts me.” There were lots of people NOT accepting this new Dylan in 1965, this new model of an old classic restores its “classic” reputation. Remember Stephen Hunt said this about it…”The temptation is almost overwhelming to simply say that if you’ve never heard this album, just go and get a copy. Buy it, get it from your local library, borrow it from a friend, do anything, but just hear it. Because this, my dear  and patient readers, is one of the finest records ever made, by anyone.” Let us add…get the new version!

and patient readers, is one of the finest records ever made, by anyone.” Let us add…get the new version!

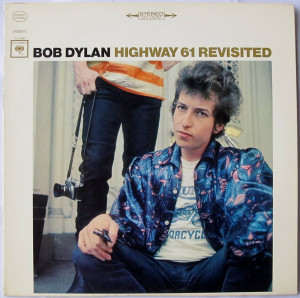

Later that same year, just in time for Christmas, came a revolution! Highway 61 Revisited was a blast of fresh air. Dylan competed with the Beatles Rubber Soul and the Rolling Stones December’s Children for

the Christmas dollars.

An anecdote from David: “I received both Highway 61… and Revolver for Christmas that year. I was listening to Dylan with another album stacked on top. My Grandmother had one too many eggnogs (more rum than eggnog, methinks) and kicked my brand new two-speaker, fold down front, portable record player with the plastic cover. The stacked album dropped onto the Dylan, sandwiching the tone arm between and rendering “Tombstone Blues” one big gouge. This is the first time in 38 years I’ve been able to listen to that tune!”

The album starts with the big hit. “Like a Rolling Stone” was, at six minutes thirteen seconds, the longest single ever played on radio…til the Beatles went a minute longer with “Hey Jude.” Produced by Tom Wilson, who carried on his duties from Bringing It All Back Home for just this one track, this was groundbreaking when it came out. Oblique, dense lyrics, somehow spoke to a whole generation. That “thin, wild mercury sound” that Dylan spoke off in his Playboy interview is modelled in this song. The remastering brings the piano up in the mix. The electric rhythm guitar is more present too. And on top of it all, Dylan’s harmonica and his whiney tenor. Then Bob Johnston takes over at the controls. Michael Bloomfield plays twisting guitar parts over the choogling rhythms. Al Kooper, Paul Griffin and Frank Owens play keyboards; Charlie McCoy plays guitar; Russ Savakus and Harvey Goldstein handle the bass chores while Bobby Griggs is the drummer. “Tombstone Blues” was worth the nearly 40 year wait! It rocks.

The insert booklet includes the back cover poem from the original vinyl, and out-takes from the photo session which document the recording sessions. The packaging on the whole set of re-mastered albums is nicely done. Not jewel boxes but rather cardboard gatefold mini-album jackets, with a plastic CD holder. In the case of Nashville Skyline there’s just an extra fold of photos, but on other albums there’s a small booklet. No extra notes. No bonus tracks. But a neat and definitive reporduction of the original albums.

One thing that is made painfully clear on the remastered version is that there are reasons for retakes. Spontaneity is not necessarily the best way to record. There is an obviously out of tune guitar on both “Ballad

of a Thin Man” and “Queen Jane Approximately.” If you’re singing along with gusto…it doesn’t matter. But if you are listening to the reproduction of the sound, and its perfection in this new system…the hairs will stand up on the back of your neck and you listen to these two songs.

David: I don’t really have anything to add to what you’ve said about Home and Highway 61. Just a few toughts about Skyline that you can take or leave. Sorry I haven’t gotten Blood to you yet. It’s been a rough few weeks. I finally realized I was restless and needed to write something today, so here it is: Nashville Skyline is a slight album, after all these years. Oh, it was a big deal in 1969 … “Dylan’s made a COUNTRY album!” Well, yeah. The Byrds did it two years earlier, and did it better, with a better band, and they sounded like they were having more fun. It’s telling that the most lasting work from these sessions is Dylan’s duet with Johnny Cash on “Girl From the North Country.” Their voices don’t blend too well, but Dylan’s doesn’t blend too well with anybody’s. But it was a symbolic meeting of what was then perceived to be mainstream and counterculture, and opened the music of each man a little bit more to the other’s fans. But the songwriting overall is fairly thin, another sign that Dylan was in a period of drifting  between two very productive periods, the late ’60s of John Wesley Harding and the mid-’70s.

between two very productive periods, the late ’60s of John Wesley Harding and the mid-’70s.

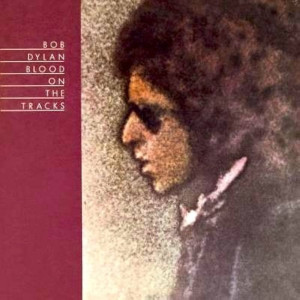

The rebirth began with a bang with Blood on the Tracks in 1974. As is all too common with singing songwriters, the burst of productivity had its roots in pain, in this case the end of a marriage. While it initially received mixed reviews, it has more than stood the test of time and is now considered a classic, one of Dylan’s best and most influential albums.

It opens with the one-two punch of “Tangled Up In Blue” and “Simple Twist Of Fate,” and once again we know Dylan is singing like he really means it. The pensive “You’re a Big Girl Now” is followed by “Idiot Wind,” one of the nastiest kiss-off songs of all time. The tuneful, hook-laden “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” is followed by the greasy blues of “Meet Me in the Morning.” Next is the tour-de-force “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts,” a rollicking Western outlaw ballad with about a million verses. Part melodrama, part parody, “Lily” is a big tale of sin, redemption, love and hubris, chock-full of fascinating characters painted in spare swift strokes. This one joins Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty,” from roughly the same era, as a masterpiece of the genre.

“If You See Her, Say Hello” and “Buckets of Rain” feature just fingerpicked acoustic guitar and bass, two folky-sounding sad love songs that hark back to Dylan’s earlier work. In between is “Shelter From the Storm,” another toe-tapper that was inspired, I believe, by an encounter Dylan had with his old flame Joan Baez — the same encounter that inspired her masterpiece, “Diamonds and Rust.”

I’m no audiophile, but it’s obvious to me that the sound has been boosted on Blood. It works most of the time, except for the fact that this wasn’t a particularly hot band. Nearly every song seems framed by the hi-hat cymbals and anchored by an electric bass that’s adequate but not world-class. Dylan was making a statement of another kind with his selection of band members, that the feeling conveyed by the music was more importance than its note for note perfection, yet another way in which the album influenced later generations of musicians.

If you like Dylan at all and you don’t have Blood on the Tracks, you should; and unless you’re some kind of vinyl junkie, this is the edition to have. Don’t bother reading Pete Hamill’s pretentious liner notes, though. Just listen and enjoy.

(Columbia/Sony, 2003)