This reviewer would not lightly claim that anyone is “a legend in his own lifetime.” In Dave Swarbrick‘s case, however, it is justified: in 1999, a zealous staffer on the London Daily Telegraph got a little carried away by news of Dave’s urgent hospitalization with respiratory problems and arranged for his obituary to be printed on April 20. When the news reached him, Dave, whose demise was alleged to have occurred in his current hometown of Coventry, remarked with characteristic good humor that it was not the first time that he had died in Coventry. He remains frail after this illness but has played occasional gigs in the last nine months to great acclaim.

This reviewer would not lightly claim that anyone is “a legend in his own lifetime.” In Dave Swarbrick‘s case, however, it is justified: in 1999, a zealous staffer on the London Daily Telegraph got a little carried away by news of Dave’s urgent hospitalization with respiratory problems and arranged for his obituary to be printed on April 20. When the news reached him, Dave, whose demise was alleged to have occurred in his current hometown of Coventry, remarked with characteristic good humor that it was not the first time that he had died in Coventry. He remains frail after this illness but has played occasional gigs in the last nine months to great acclaim.

Even if Swarbrick had not so dramatically returned from the grave, he could still be considered almost legendary. Followers of the English folk music scene will be familiar with a career that goes back to the early 1960s. Swarbrick achieved prominence on the thriving folk revival scene of the time through his work with the Ian Campbell Folk Group and his association with some of the Charles Parker/Ewan MacColl “Radio Ballads.”

But it was probably through his collaboration with the singer and guitarist Martin Carthy in a series of recordings, in which Swarbrick’s violin brilliantly complemented Carthy’s singing and playing of traditional songs that Swarbrick both attained greater prominence as a musician. As a result of this increased visibility, Swarbrick was invited to guest with the up-and-coming London-based rock group, Fairport Convention on their 1969 album Unhalfbricking. When the group was obliged to reorganize following a tragic road accident during this same period, Swarbrick was invited to become a full member. As the band moved away from the influences of contemporary American West Coast sounds and turned instead to electrified — and electrifying — performances of traditional songs from Britain, Swarbrick’s folk experience was put to great advantage. The character of this group’s approach effectively obliged Swarbrick to become a pioneer of the electric violin, not an established instrument at that time but now, of course, commonplace. (By an amusing irony, Swarbrick’s old partner, Martin Carthy, was in turn sucked into the other major British folk rock band of the 1970s, Steeleye Span.)

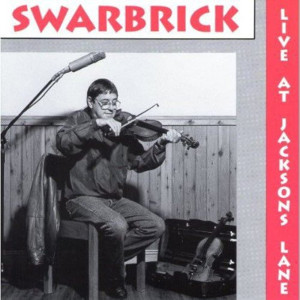

It was during some 15 years with Fairport that Swarbrick developed new talents as both a singer and a songwriter and also suffered severe hearing damage that eventually obliged him to stop playing electric music for a living, although he can still be found guesting with Fairport Convention at periodic reunions of alumni. However, he never lost his links with the more mainstream traditional music. The present CD is a live recording of a solo concert by Swarbrick in London in 1991 and shows his talents as a performer of traditional songs and tunes as well as of tunes composed in the traditional style. There is only one Swarbrick original on this CD, a slip jig called “The Pepperpot,” and I would not have known this was an original if the record cover did not say so (and indeed Swarbrick admits it in his recorded introduction).

The first piece on the CD is a song that Swarbrick must often have performed with Fairport, “The Bonny Black Hare,” one of those folk songs full of double meanings that pretends to be about something else but is really about sex. He does not have a remarkable voice. Even in his heyday with Fairport Convention, he was never an outstanding vocalist, and his breathing problems and indulgence in tobacco certainly have not helped. But he is capable of singing in tune and of enunciating words clearly while playing a melodic accompaniment on the violin, all of which makes listening to his performance of the three songs on the CD quite agreeable.

This opening song is followed by two sets of tunes, the first taken at an increasingly fast pace, while the second set consists of slow pieces. The juxtaposition of these two tracks provides a good opportunity to measure Swarbrick’s skill at different tempos. He can scatter notes frantically when required, but he’s also a master of the lyrical, drawn out bowstroke.

These tunes are followed by the traditional song “Lovely Nancy,” during the introduction of which Swarbrick explains that he has accompanied everyone else singing it and “the words must just have rubbed off.” Again, the vocal quality is outmatched by the violin accompaniment, but the song comes across well enough. The song with which Swarbrick concludes the concert is a daring choice, no less than “The Two Magicians” (Child Ballad #44). He might have done this in order to invite comparisons with the well known recording made by Steeleye Span, but his is a variant version and sounds so different in a voice and violin performance that thoughts of rivalry are irrelevant. It is particularly interesting to hear how Swarbrick’s violin provides a very full backing to his singing: he varies the form of the obbligato playing under successive verses, which are interspersed with vigorous solos.

Before this final song, there are four further tune-sets representing a veritable tour of the British Isles as well as of different forms and rhythms. I would make particular mention of a moving interpretation of O’Carolan’s “Sheebeg and Sheemore,” a staple of the repertoire of many Irish bands. Swarbrick demonstrates in an inventively embellished interpretation that a violinist raised in a mainly English tradition can use his immense talent to compete successfully with the Irish fiddling tradition. Another piece that particularly pleased me was “Sailing Into Walpole’s Marsh,” which I had long enjoyed as one of the instrumentals on the extraordinarily brilliant album that by Paul Brady and Andy Irvine made in 1976 and which simply bears their two names as a title.

Musikfolk has done fans of Dave Swarbrick a great service in issuing this CD. It showcases his effortless mastery of the folk violin in an extremely diverse collection of pieces and is highly recommended to lovers of this genre. He acquits himself well on the three songs too, and if you think that three songs don’t give you enough of the Swarb voice, be reassured. The instrumentals are punctuated by frequent grunts and interjections that make Glen Gould and even Steffi Graf sound like mutes by comparison.

(Musikfolk, 1999)