Who was it that said, “Many of the best Celtic CDs are self published?” (Hint: Russian Stout), and who last remarked that one of the best things about reviewing for GMR is being surprised and delighted by something truly wonderful? Well, brothers and sisters, I’m here to testify that both are true! Cran’s third album, Lover’s Ghost, is Irish traditional music at its best, mixing amazing songs and stunning instrumentals.

Who was it that said, “Many of the best Celtic CDs are self published?” (Hint: Russian Stout), and who last remarked that one of the best things about reviewing for GMR is being surprised and delighted by something truly wonderful? Well, brothers and sisters, I’m here to testify that both are true! Cran’s third album, Lover’s Ghost, is Irish traditional music at its best, mixing amazing songs and stunning instrumentals.

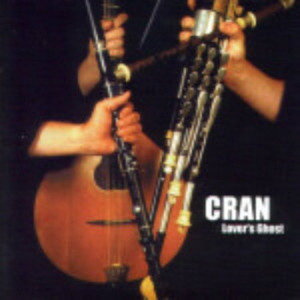

Cran are Seán Corcoran on lead vocals, bouzouki and guitar; Ronan Brown on uilleann pipes, whistles, flutes, keyboards and vocals; and Desi Wilkinson on flutes whistles and vocals. All three have a long list of credentials and various solo projects, as well as collaborating in this ensemble. Their experience is reflected in Cran’s ability to project a rare sense of primitive sophistication through their selection of lesser-known songs, vocal arrangements, and musicianship. This is a powerful album, achieving its effect without showing strain or resorting to anything resembling “loud and fast.” Cran exhibit the sort of depth that younger musicians can only dream about, proving once again that the Celtic folk traditions reward the dedication that leads to mastery.

It took me a long time to develop a taste for slow unmetered Irish singing, either Gaelic or Hiberno-English, partly because I find that the vast majority of soloists lack the power that can be achieved in ensemble singing. But Cran demonstrate the beauty of this style, making artful use of Corcoran’s reedy tenor vocals, joined by Brown and Wilkinson for a verse or chorus. The songs range from work songs to spurned lovers, lonely immigrants to prisoners of fairy. What makes Cran’s treatment unique is their arrangement and adaptation of the songs, making the familiar themes seem fresh and mysterious.

One of the best songs is “Stolen Bride (An Bhean a Tugadh As),” an adaptation of a nineteenth-century song about a young woman stolen by the fairies, using her lullaby to a fairy child to send a coded message to a nearby washerwoman with directions for her release. Corcoran sings the melody over a short chanting refrain by the three vocalists, whose joined voices communicate a sense of her frustration in trying to bridge a gap between worlds and catch the attention of the washerwoman.

The other standout is a song from the Hebrides, sung in Scots Gaelic with translation verses, called “Newry Boat Song (Mo Ghille Dubh-dhonn).” It is sung from the point of view of a spurned lover whose betrothed has left the island and sailed to Newry for seed potatoes, only to stay on and marry a local girl. The combined voices of the trio create a sense of the jilted lover’s despair, as does the rhythmic chorus.

Two immigrant songs grace the album. “Erin Grá Mo Chroi” is a poignant original about an immigrant to New York, taking a walk to “gaze on the scenes of New York” while dreaming of home, with the flutes capturing the sense of wistful longing. “Captain Thompson,” a nineteenth-century song telling of an immigrant’s storm-tossed journey to Quebec, uses Corcoran’s voice to convey the isolation and longing for home. Browne’s pipes create a very mournful sense of the immigrant’s resignation, even while toasting the Captain’s skill at getting them safely through the squall off Newfoundland.

It’s difficult to explain in print, but Cran have an amazing sense of the language of sounds, the souls of the instruments, and they know how to use them to create the emotional atmosphere that the lyrics convey in words. Many of the vocals gain their sense of power through the repetition of chanting, such as in “Stolen Bride” or “Hó Bó.” The latter song has an unusual melody and is a work song sung for ploughing, a type of song which the liner notes report had died out by the end of the nineteenth century. After hearing this odd and haunting song, I have a better understanding of the appeal of “The Ploughman.” (For a great version of this song, see Dervish’s Harmony Hill). “Na Ceannabháin,” a pleasing jig song that opens an otherwise instrumental set, also has that repetition and joining of voices.

The instrumentals are effectively placed and well balanced, enjoyable in their own right and creating anticipation for the next song or tune. I particularly liked the pairing of the flute and pipe in the introduction to the slow air “After Dawning,” followed by a lovely uilleann pipe solo. Cran are incredibly effective at creating a sense of tension and pacing in the slow songs – yet another thing that sets them above many of their contemporaries. These guys know how to take turns, also, switching between pipes and flutes for the melody, making full use of the trio’s musical vocabulary.

Cran also use vocal arrangements to create continuity with their instrumentals. The drone of the pipes is part of what gives them a sense of magic. Like the digeridoo, there is just something exciting about that constant low sound. Yet vocal drones can create that same sense, and Cran does just that on “Oakum (Sé Oakum Mo Phriosúin),” a mournful ballad of an oakum picker, sentenced to the workhouse to pull ropes apart for use in caulking ships.

Have I used enough superlatives yet? If you want to really experience Irish traditional music, to get beyond the flash of young and enthusiastic traditionalists, or loud and fast rock adaptations (fond as we are of them!) to the generative substrate where the magic is created, you should get this album. It demonstrates both mastery and artistry. But be warned: it may be difficult to remove from the CD player.

(Black Rose Records, 2000)