I learned a very important concept about making art in a dance class, studying butoh, the contemporary Japanese dance-theater that is at once highly abstract and fundamentally impressionistic: evocation. Our movements were not to describe an action, but to evoke the image of the action. This applies to works done in many mediums, from dance to poetry to fiction and, of course, music.

Coyote Oldman (Michael Graham Allen on flutes, Barry Stramp on recording studio) has explored a range of possibilities inherent in this idea, basing their music on the sounds and textures of New World flutes (for the most part, made by Allen).

Tear of the Moon, released in 1989 (or 1987, depending on whether one believes the listing on In Beauty I Walk or the CD itself), reflects their early philosophy: “We are not here to romanticize the past or idealize a particular culture. . . . We are stretching the most advanced recording technologies to talk about something which is timeless in all people, all cultures.” The working method was in real time: while Allen was playing the flutes, Stramp was processing the sounds, providing a unique kind of feedback that certainly added to the whole. “Tear of the Moon” itself, the lead track on the album, is a tremendously evocative piece, a mellow, mid-tone melody given a slight echo and balanced against a higher-ptiched countermelody; ultimately the composition is mesmerizing. The melody/countermelody technique is used extensively throughout, providing a highly impresssionistic music that becomes hypnotic. (A little bit of reverb never hurt anyone, and does add a measure of depth.) “Lunar Symphony” and “Dawn” are particularly rich, and in the latter Allen slips into birdcalls, all done on the flute, and one of the rare instances in which such devices add to instead of subtracting from the music. (And perhaps a subtle reminder to the new age “nature sounds” school that the place of music vis-à-vis nature is pretty much the opposite of what most of them seem to imagine.)

Tear of the Moon, released in 1989 (or 1987, depending on whether one believes the listing on In Beauty I Walk or the CD itself), reflects their early philosophy: “We are not here to romanticize the past or idealize a particular culture. . . . We are stretching the most advanced recording technologies to talk about something which is timeless in all people, all cultures.” The working method was in real time: while Allen was playing the flutes, Stramp was processing the sounds, providing a unique kind of feedback that certainly added to the whole. “Tear of the Moon” itself, the lead track on the album, is a tremendously evocative piece, a mellow, mid-tone melody given a slight echo and balanced against a higher-ptiched countermelody; ultimately the composition is mesmerizing. The melody/countermelody technique is used extensively throughout, providing a highly impresssionistic music that becomes hypnotic. (A little bit of reverb never hurt anyone, and does add a measure of depth.) “Lunar Symphony” and “Dawn” are particularly rich, and in the latter Allen slips into birdcalls, all done on the flute, and one of the rare instances in which such devices add to instead of subtracting from the music. (And perhaps a subtle reminder to the new age “nature sounds” school that the place of music vis-à-vis nature is pretty much the opposite of what most of them seem to imagine.)

Compassion, released in 1993, shows Allen and Stramp, aided and abetted by extraordinarily clear vocals by Hui Cheng, headed in a direction which eventually met the “space music” contingent of new age composers: the manipulation has become a major element, although Stramp also actually plays flutes on some tracks. In many places the flutes lose their identity: we are are left with just sounds – they are evocative sounds, but the breathy, yearning quality that makes the Plains flute what it is is almost entirely lacking. This is moody music, almost dark, and in the most successful tracks, such as “Dignity” and “Made of Stars,” the emergence of the flute as a clear voice imparts a dimension of poignancy that might not otherwise be possible. This is no longer a matter of artists building on traditions, but more an example of artists following a direction that suggests itself as they work. That they found it in some measure valid is evidenced by the fact that later collections took it still farther.

Compassion, released in 1993, shows Allen and Stramp, aided and abetted by extraordinarily clear vocals by Hui Cheng, headed in a direction which eventually met the “space music” contingent of new age composers: the manipulation has become a major element, although Stramp also actually plays flutes on some tracks. In many places the flutes lose their identity: we are are left with just sounds – they are evocative sounds, but the breathy, yearning quality that makes the Plains flute what it is is almost entirely lacking. This is moody music, almost dark, and in the most successful tracks, such as “Dignity” and “Made of Stars,” the emergence of the flute as a clear voice imparts a dimension of poignancy that might not otherwise be possible. This is no longer a matter of artists building on traditions, but more an example of artists following a direction that suggests itself as they work. That they found it in some measure valid is evidenced by the fact that later collections took it still farther.

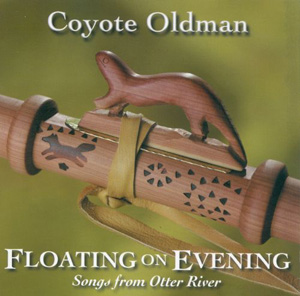

Floating on Evening (1998) reveals Allen in a mood that moves closer to the traditional sources of his music: the solo flute, accompanied only sporadically by guitar or piano (provided by Horace Williams with exactly the right degree of understated simplicity), and Barry Stramp acting in a very straightforward capacity as recording engineer and producer. The whole does indeed evoke evening on a quiet river, and somehow Allen manages a thread of unity without its becoming the sameness that all too often infects new age collections by a single artist.

Floating on Evening (1998) reveals Allen in a mood that moves closer to the traditional sources of his music: the solo flute, accompanied only sporadically by guitar or piano (provided by Horace Williams with exactly the right degree of understated simplicity), and Barry Stramp acting in a very straightforward capacity as recording engineer and producer. The whole does indeed evoke evening on a quiet river, and somehow Allen manages a thread of unity without its becoming the sameness that all too often infects new age collections by a single artist.

To many people, to talk about the role of “tradition” in something as cobbled together as new age music may seem ridiculous, but it all had to start somewhere. That Native American attitudes and philosophies have impacted the whole new age movement is quite obvious; the integrity of what has resulted from that impact is quite often debatable. We live in what some have called a “piratical culture,” borrowing and appropriating whatever seems appealing. And if, as some maintain, concepts and practices – in other words, traditions – follow the physical instruments, it can be interesting to see how those borrowings are modified. In this case, to worry about purity is irrelevant: the traditions are a starting point and a tool, as are the instruments themselves. I can’t say that I find a great deal of intellectual rigor in this music, but that is not the point. Evocation is not only a valid pursuit, but often a necessary one, if an artist is to be true to the meaning of his work.

(Perfect Pitch (Xenotrope Music), 1989)

(Perfect Pitch (Xenotrope Music), 1993)

(Xenotrope Music (Coyote Oldman Music), 1998)