Liz Milner penned this review.

Liz Milner penned this review.

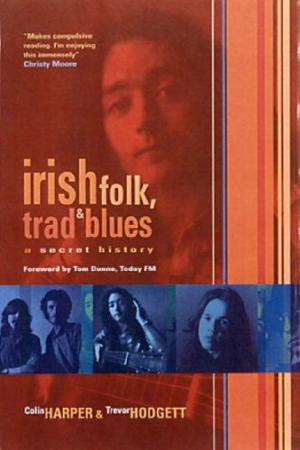

Irish Folk, Trad And Blues is a sprawling, overcrowded, rush-hour subway car of a book that piles on more eccentric musicians, frenetic booze-ups and unscrupulous music industry types than my brain could keep track of. It is a collection of essays and previously published reviews and interviews that covers roughly thirty years of Irish, English and American music-making (from 1962 to 1998). The book explores the history of the English and Irish Folk Music Revivals of the 1960s, Van Morrison and Them, the Blues boom in Northern Ireland, Irish Rock, Irish Folk Music in the 1970s, The Irish Trad Revival, and the Folk Music Revival of the 1990s.

Harper and Hodgett are almost heroic in their attempts to show how the Irish, English and American music scenes cross-pollinated each other. The relationships are so tangled, however, that instead of a clear line of development, one gets the conceptual equivalent of the glom that results when you leave spaghetti sitting too long in the pot. Like the “six degrees of separation” game, the significance of all these relationships gets lost in the tangle. (Some Peter Frame-style Rock “Family Trees” would have helped immensely, especially in charting the endless permutations of Them).

Harper and Hodgett begin the book by launching into an account of “Sweeney’s Men,” with no discussion of the roots of Irish Folk Music — Gaelic or English. Since a lot of Americans think Irish folk songs are what Bing Crosby sings, this is a sad omission. Also, from reading this book, I got the impression that the Irish Folk Music Revival sprang full blown out of Anne Briggs’ head, for Harper and Hodgett devote a big chunk of the first section of the book to discussing singers and performers who were identified with English — not Irish — folk music, such as Anne Briggs, Davey Graham, Tim Hart, and Maddy Prior.

There is also no mention of people such as Sean O Riada and his pioneering folk group of the early 1960s, Ceoltoiri Cualann, and there’s also no explanation of why folk ensembles suddenly started appearing in Ireland during the late 1950s. Was it the influence of American groups such as the Weavers? The success of the Clancy Brothers?

The book’s greatest strength is on the micro, not the macro level. While the connections between the various phases of the music’s development are difficult to follow, Harper and Hodgett’s profiles of the artists are often fascinating. They give gripping and in-depth accounts of Van Morrison’s early career, the trials and tribulations of Henry McCullough, the withering away of Rory Gallagher, and much, much more. They have a huge and varied cast of characters to chose from, including Henry McCullough, Jimi Hendrix, Van Morrison and Them, Sweeney’s Men, Terry and Gay Woods, Jim Daly, Planxty, De Danann, Wings, Arlo Guthrie, Andy Irvine, Steeleye Span, Pentangle, Davey Graham, Townes Van Zandt, Anne Briggs, Johnny Moynihan, Ornette Coleman, Horslips, Rory Gallagher, Clannad, Altan, Martin Hayes, Bert Jansch, John Fahey, Stockton’s Wing, Kevin Burke, Christy Moore, Muddy Waters and many more musicians from Ireland, England and the U.S.

Though the authors’ knowledge and enthusiasm for the music is hard to resist, their writing is marred by hack phrases. They use superlatives such as “unbelievable” so often that it is unbelievable. Occasionally they stoop to the hack’s trick of pressure-cooking fake poignancy and portentousness into their writing; “I wouldn’t have been surprised if a tear had started to trickle down his face,” and, “the history of Irish music might well be significantly different.” The book also seems a bit flabbed up. There are several instances where both authors’ reviews of the same performance are given. Since Harper and Hodgett generally agree with each other and since their backgrounds are so similar, it’s like reading the same article twice. The tendency toward bloated, overstuffed sentences leads me to believe that the authors were being paid by the word. To give an example, Colin Harper writes,

Once the notion of this book was up and running, no longer, I deemed, could that unopened box labeled “Mellow Candle” be ignored. Few writers, it may be conjectured, have such a box (and I am speaking metaphorically here — I believe it unlikely that anyone in the world, with the possible exception of former Candle Alison O’Donnell, actually has a box with such labeling on it). Many writers, however, will have something else in its place — an aspiration to tackle, at some indeterminate point in their careers.

Some of the writing is cringe inducing: “I determined to sneak back in for the evening and build a stable door of celluloid posterity just before the horse finally bolted.” (Colin Harper writing about Horslips).

Occasionally, the authors let the artists speak for themselves with wonderful results. Ottilie Patterson, a pioneering Irish Blues Singer, recounts the start of her career with wonderful vivacity. When she was invited to join the Chris Barber Band, she replied with a telegram, ‘”Coming if I have to ride the rods.” In her interview she added, “I didn’t even know what riding the rods was, but I knew it was a real blues thing.” The poignancy that Patterson brings to the book is real. After she recounts some wonderful stories of her life on the road, she notes that the Black Blues singers who visited from America accepted her immediately, while the members of her own band could never acknowledge that a woman could be their equal. The strain of touring with her male chauvinist colleagues finally led her to quit performing altogether.

The book also contains a very useful ten-page annotated Selected Discography, profuse black and white photos, and a brief tip of the hat to Green Man Review‘s Senior Writer John O’Regan as “a remarkably prolific writer and broadcaster.”

There is something in this book for everyone; it’s a pity that the authors didn’t do a better job of editing out the flab.

(Cherry Red Books, 2005)