Everyone knows Christy Moore, a central figure in the Irish folk revival of the 1960s and indirectly a significant contributor to the English folk revival that paralleled it. We know of his work with Moving Hearts and we are familiar with his earlier role in the highly influential Planxty, in both of which his path crossed with those of several other leading traditionally-inclined Irish musicians. The cross-fertilization of the Planxty years produced a series of solo and collective ventures by Moore that have built on and developed Irish folk and folk-derived music down to the present day.

Everyone knows Christy Moore, a central figure in the Irish folk revival of the 1960s and indirectly a significant contributor to the English folk revival that paralleled it. We know of his work with Moving Hearts and we are familiar with his earlier role in the highly influential Planxty, in both of which his path crossed with those of several other leading traditionally-inclined Irish musicians. The cross-fertilization of the Planxty years produced a series of solo and collective ventures by Moore that have built on and developed Irish folk and folk-derived music down to the present day.

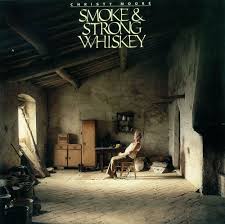

Well, you should note that this reissued CD does not feature that Christy Moore or that music — at least, hardly, even if Moore occasionally nods towards traditional forms and calls on a number of compatriots from the folk tradition to accompany him. This is the other Christy Moore, present to varying degrees in the earlier groups already mentioned and more so on his numerous solo albums. It is Christy the roaring boy, Christy the politically committed activist, Christy the cynical and world-weary social commentator, Christy the star able to laugh at himself, Christy the contemporary musician, using fashionable sounds and styles. You may see familiar names from the folk world in the credits (Donal Lunny, Declan Sinnott, Sharon Shannon and Davy Spillane, to name only the ones most familiar to me) but the instrumentation tells you what to expect: alongside the acoustic guitars, bowrawn (sic), accordians (sic) and flutes there are saxaphones (sic), electric guitars, horns, Hammond organs, pianos and other keyboards and assorted percussion. (Please excuse my numerous “sics;” a German company re-issued this CD and there are plainly some linguistic hurdles that were not overcome.)

The choice of songs, too, is a long way from the traditional repertoire; indeed, there is not one “trad.” in sight, not even a “trad. arr.” Instead we have three of Moore’s own compositions, plus three co-written with other musicians, including Shane McGowan, one of whose own songs is also featured. There is also a “foreign” song, written by Ewan McColl (sic); although it turns out to be a lament about the evils inflicted on Ireland, so it is not really out of place on this CD. For this recording is a prime example of what might (since I just invented it) be called “hibernitude,” by analogy with the “negritude” of French-speaking black intellectuals of the age of decolonization.

By “hibernitude” I mean Irishness, the very fact of being Irish, and it is hibernitude that provides the essential context of this album. It is Moore’s singing about Irish politics, Irish society, Irish history, Irish experiences, Irish sentiments and an Irish consciousness that impart a meaning and a coherence to the CD. Being Irish, in this sense, is more than an ethnic, geographical, political or historical fact. It means more than simply holding an Irish passport: it is an existential condition.

Of course, many musicians, especially from third-world countries, express their ethnic or cultural origins in their music, but they do it by exploiting or adapting traditional forms, by referring to musical styles acquired from their ancestors. This, on the other hand, is a collection of pop/rock-styled songs in transatlantic form but bursting with Irishness. I cannot think of an American or British artist who could produce an equivalent album: I was just listening, by chance, to a compilation of the Kinks’ recordings and there is no doubt that a certain Englishness pervades some of their songs, just as it does many of Billy Bragg’s compositions, but the Irish have such a clearly defined identity that there is nothing casual or contingent about Moore’s sense of belonging to a people with a potent psychological and historical baggage. It was only after I had finished writing this review that I took a look at what GMR colleagues had written about Moore, and guess what I found: David Kidney, writing about the 1999 reissue of Live in Dublin writes that the songs are linked by their “Irishness”!

The CD opens with a real tour de force, Moore’s own “Welcome To The Cabaret.” This is a driving and sardonic song, partly spoken rather than sung in an exaggerated version of Moore’s always distinctively Irish accent, which I interpret as a commentary on Moore’s not-quite-star status in his own country: respected but not too highly respected, recognized without people necessarily remembering exactly who he is, worth seeing provided there is nothing better on TV. It is a funky, soul-based arrangement, with a blasting wind section and some high-flying electric guitar from Jimmy Faulkner, all of which would be as much at home in Memphis as in Dublin, that suddenly turns into self-mockery when Moore launches into some contextually inappropriate mouth-music over a rock backing. This is followed by another very powerful song, Shane McGowan’s “Fairytale of New York,” a waltzing anti-Christmas anthem driven by piano, accordion and Hammond organ that continues the mood of Irish introspection with a mixture of love and loathing, of bravado and insecurity. McGowan also receives composer credits for “Aisling,” sung in the broadest Irish-English, and about the closest thing to a lovesong on the album, even if the loved one has to compete with Irish republicanism and emigration, the twin enemies of a happy and settled domestic life.

There is more reflection on Irish life in the title song, more self-deprecation and mockery as Moore describes a timeless, self-deceiving and complacent but frequently rotten social order. Less specifically Irish, but certainly highly relevant in a country that still contains major pockets of social conservatism, is the atmospheric “Burning Times,” which I can only describe as a feminist rallying cry, invoking in appropriately reverential tones the ancient goddesses of different epochs and cultures and contrasting them with their mortal foe, the dead hand of Catholicism, which is still a force to be reckoned with in Ireland. (If you want an illustration of what I mean by this, set in our own lifetime, go see the recent film The Magdalene Sisters).

If these songs are social comment, other tracks are much more directly political. “Scapegoats,” penned by Moore and E. (Eamonn?) Cowan is a sad and understandably bitter song about the Birmingham Six, imprisoned and later (much later) released after being convicted on the flimsiest of evidence of the murderous explosions that ripped through two pubs in England’s second city — incidentally destroying the pub where I met my wife on a blind date. Musically, it uses a deceptively quiet narrative style to build up a sense of the horror experienced by men wrongfully imprisoned and gathers additional power from the refrain that repeats the names of the six protagonists.

Moore’s song “Whacker Humphries” is another tale of injustice, using a similar rollicking narrative arrangement, describing how a group of concerned parents who tried to clean the heroin peddlers off the streets of their district of Dublin, when the authorities would not, ended up in court themselves; ostensibly, in Moore’s view, for threatening the cosy entente between those same authorities and the dealers. As Moore sings, “One man gets a pension and another man gets time.” If the mood of the CD that emerges from the preceding paragraphs seems a somber one, despite the ironic humour lurking in places, little relief is found in the remaining songs. The countryish “Blackjack County Chains” is a jail song of a uniformly depressing nature, brilliantly moved along by some fine slide guitar from the wonderful Declan Sinnott. “Green Island,” the Ewan MacColl song, begins with the noise of waves breaking and then proceeds with only percussion (bodhran) accompanying Moore’s voice as he details the wrongs and the suffering inflicted on the Irish people over the centuries. The song ends with the mournful beauty of Davy Spillane’s flute leading us back to the sound of the sea.

The final song at last lifts the mood: “Encore” is Moore’s own account of how he was bitten by the folk-music bug in his youth and how performance still gives him an unequalled lift: “If I get an encore I can go home feeling like a king.” Christy Moore has had many an encore and let us wish him many more of them. This is a CD for those who like Moore’s music rather than for lovers of Irish folk music. Traditionalists may be disappointed, although the groups to which Moore belonged certainly did not confine their repertoire to traditional music and provided a foretaste of this kind of recording. There is here, for those prepared to listen, an apparently effortless marriage of contemporary songs with an eclectic musical style that seamlessly blends traditional and modern elements into this celebration of hibernitude.

(Grapevine, 1999)