Debbie Skolnik wrote this review.

Debbie Skolnik wrote this review.

It’s serendipitous how sometimes you find a “new” artist via a cover version of a song. In this case, the song was “No Gods and Precious Few Heroes,” which I first heard on Dick Gaughan’s wonderful 1996 album Sail On.

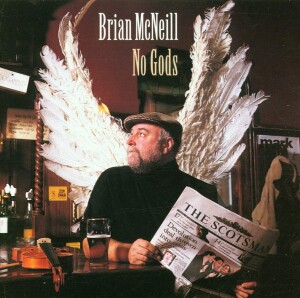

A CD called No Gods by Brian McNeill popped up for review, and I immediately latched onto it. It seemed too coincidental not to be the same song – and I was right. I confess I didn’t recognize Brian McNeill’s name immediately (shame on me, since he was one of the founding members of the well-known and long-lived Battlefield Band, started in 1969 and still going strong although without McNeill, who left in 1990 to concentrate on his solo career).

Skirling bagpipes and a full horn section at a furious pace preface the vocals to the title song (also the first track on the album), which debunks the “all the ridiculous, over-romanticised baggage of Scottish history.” What good are the “heroes” like Bonnie Prince Charlie, asks McNeill, when so many of the present-day Scots still live a hand-to-mouth existence?

One of the very strongest songs on the album is “Any Mick’ll Do,” a diatribe against the xenophobia and intolerance that has bedeviled mankind all over the world since the beginning of human civilization. Although the song focuses on the long legacy of British-Irish intolerance, particularly the British judicial system whose inherent bias makes a mockery of the idea of a fair trial, it expands to include all of the scapegoats of the world: “Any mick’ll do, any black, any Jew, any poor wee bugger who’s not like you.” This is sung in almost a hypnotic rhyming rhythm. In an obviously satiric twist, McNeill goes on to say “I hate every Jew who kicks a Palestinian, and every Nazi who ever kicked a Jew. I hate every stupid, bigoted opinion and if you don’t hate them too, then I hate you.”

McNeill’s lyrics on this album predominantly showcase his political feelings. However, he balances them (and his quite palpable anger at the state of today’s world) with instrumentals that create quite a different mood, and a moving tribute to his maternal grandfather. “Trains And My Grandfather” is a poignant remembrance, not only of the pleasure of his grandfather’s periodic visits with him from childhood through his early thirties, but of the sad task of saying a final goodbye when the inevitable passing of his grandfather occurred.

He also looks back into Scottish history in such songs as “Montrose,” in which he assumes the persona of a little boy innocently asking his father why the Marquess of Montrose is considered a traitor and is to be hanged. Turns out that Montrose (whose real name was James Graham Montrose), a 17th-century soldier in the service of the Stewarts, misjudged their reciprocal loyalty to him and was condemned to die by Charles the Second.

He explores the subject of domestic violence in “Steady As She Goes,” in which a woman finally gets up the courage to end an abusive relationship by walking out on it.

The album’s closer is “Bring Back The Wolf,” which calls for the re-invigoration of the Scottish Highlands’ economy so that the people who love it can afford to live in it. Here McNeill applies a touch of cynical humor to the very serious reality of the situation (“Hey there, brother bear – what’s it like out there? Nice cave, nice view, is there room for two? Could you tell me who to call? Because we don’t need a lot – just a bit of what you’ve got. Just enough to feed our children and leave them walkin’ tall”).

McNeill’s extensive liner notes are invaluable in understanding both the topical and historical allusions, and include the lyrics. Even the instrumentals’ inspirations are explained.

Although most of the instrumentals sound traditional, only one of them, “The Breton Wedding March,” actually is. All others were composed by McNeill. Almost all of them will get you out of your seat and dancing around the room, with their infectious rhythms. “Miss Michison Regrets” has a minor-key, almost Semitic tune, with accordion taking the lead melody and prominent bass counterpoint.

Musically, the arrangements of most of his songs on this album fall firmly into the folk-rock camp, with an emphasis on the “rock” due to a strong rhythm section in the full-band songs. There are some exceptions: the poignant “Trains and My Grandfather” has only a simple piano accompaniment, which is all that it needs.

McNeill is joined by former Battlefield Band mates Dougie Pincock and Davy Steele. Also on the album are Patsy Seddon (from the group Sileas) playing harp and on backing vocals, Gary Coupland, Mike Travis, Brian Shiels, Ian Johnston, Steve Kettler, and Simon Van Der Walt (the last three comprise the horn section from the title track and also play on “Montrose” and “Bring Back The Wolf.”). McNeill himself plays seven instruments (all very competently) and sings on this album. (Most of us would be happy to play one instrument well or sing!)

He also does a great job sequencing his songs on the album – each one seems to belong exactly where he’s placed it. I appreciate this skill very much; I have heard countless albums where either the artist didn’t have control over the final track order or didn’t have the wisdom to know how to sequence things.

I look forward to exploring some of his other works – he has nine albums to his credit – and has also written two novels, The Busker (currently out of print) and its sequel, To Answer The Peacock (also the title of his latest CD). This man must never sleep – his muse must be constantly waking him up with new ideas!

I highly recommend this album – each time I listen to it, there’s something new to find in it, which gives it staying power in my CD player.

His Web site is chock full of information and insights into this very interesting and talented performer. He will be touring in 2000 with Dick Gaughan.

(Greentrax, 1996)