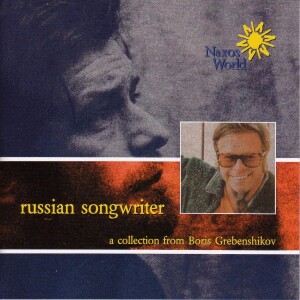

A long time ago in a mythical, long-forgotten land known as the Soviet Union, a young man named Boris decided to write and sing songs. A native of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Boris Grebenshikov became arguably the most renowned figure in the Soviet underground music scene in the late seventies and eighties, and has frequently been referred to as “the Russian Bob Dylan.” Backed by a frequently changing assortment of musicians known as Akvarium, Grebenshikov has written and sung an enormous volume of songs over the last thirty years. His blend of catchy, singable melodies and dark, often surreal lyrics has earned him a legion of followers, and a handful of detractors as well. Grebenshikov has even made a pair of albums for English-speaking audiences along the way, including 1989’s “Radio Silence,” which had an excellent but overlooked single in its title track. Still, the overwhelming majority of Grebenshikov’s work has been in his native Russian language. In this collection, he presents a number of his songs that characterize the Russian singer-songwriter tradition, along with his own versions of one traditional song and three covers of Russian songwriters who exerted a particularly heavy influence on him.

A long time ago in a mythical, long-forgotten land known as the Soviet Union, a young man named Boris decided to write and sing songs. A native of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Boris Grebenshikov became arguably the most renowned figure in the Soviet underground music scene in the late seventies and eighties, and has frequently been referred to as “the Russian Bob Dylan.” Backed by a frequently changing assortment of musicians known as Akvarium, Grebenshikov has written and sung an enormous volume of songs over the last thirty years. His blend of catchy, singable melodies and dark, often surreal lyrics has earned him a legion of followers, and a handful of detractors as well. Grebenshikov has even made a pair of albums for English-speaking audiences along the way, including 1989’s “Radio Silence,” which had an excellent but overlooked single in its title track. Still, the overwhelming majority of Grebenshikov’s work has been in his native Russian language. In this collection, he presents a number of his songs that characterize the Russian singer-songwriter tradition, along with his own versions of one traditional song and three covers of Russian songwriters who exerted a particularly heavy influence on him.

The accompanying CD booklet is 20 pages thick, containing the Russian lyrics of all fifteen songs, along with translations into English, French, and German. Bizarrely, and unfortunately, the makers of this album went through the trouble and expense of putting together such an abnormally thick booklet, yet failed to include any substantial detail that would have enhanced the listeners’ understanding of the songs. I don’t see why having Grebenshikov provide a quick explanation of the story or inspiration behind each song would have been unreasonable. In particular, I’d have liked to have known something about the historical context for the songs, whether they were written before or after the Soviet collapse, and what events shaped them. It isn’t even clear from the booklet whether these recordings are the original ones, or whether they were re-done for this project. Where Grebenshikov sings other people’s songs, I would have liked to know more about who these people were, what influence they had on Grebenshikov, and why that particular song was chosen for inclusion on this album. The brief liner notes, written by album producer Dolores Canavan, do contain some useful information, but sentences like “During the days of the Soviet Union, artists like Vysotsky, Vertinsky, and Okudjava pioneered the Russian singer-songwriter style,” seem to be aimed at people who already know enough about Russian music to know who these people are. Russian Songwriter is an album that could have ably served as a means of introducing curious listeners to a genre of music, but it is packaged in a way that will deter much of its potential audience.

Fortunately for me, I used to share my office with somebody who happens to come from St. Petersburg. Irina Gorodetskaia may not be an authority on Russian music and poetry, but she’s in a better position than I am to comment on Grebenshikov’s lyrics and the context of his songs. For a dissenting opinion on Grebenshikov, Irina enlisted her friend Nikolai Galkin. I am very grateful to both of them for their assistance. Both had interesting comments concerning the cryptic nature of Grebenshikov’s lyric writing. The English translations in the CD booklet evoke some strange, difficult imagery, and apparently it’s not just an artifact of the translations. For one thing, there appears to be a definite clash between the traditional and the modern. According to Irina, Grebenshikov “combines Russian folklore style and characters with informal street language and spiritual, difficult to catch meaning … He uses old Russian language a lot, which sounds very beautiful and poetic. His poetry floats, with smooth transitions in sound, but unexpected turns in plots.” Nikolai describes Grebenshikov’s approach as “Russian city folklore,” but considered the lyrics to be “always esoteric,” and added that “only a few Russians seem to find any meaning here.”

The album opens with “My Little Loom,” a traditional Russian ballad about a lady weaver who’s lost her love to another woman. Musically, the song alternates between a waltz in the verses and a polka in the chorus. Folk instruments dominate the arrangement, particularly the accordion and fiddle, and the song will not sound especially foreign to anyone familiar with Eastern European folk music. The second song “Gertruda” is a waltz, again dominated by the accordion, although also featuring some electric guitar. The chorus is very distinctive, and I’m sure quite memorable to Russian listeners. “Gertruda” is followed by the album’s most upbeat song, “Nikita of Riazan,” which features a driving acoustic guitar presumably played by Grebenshikov himself. The lead instrument here is a wind instrument, either a shawm or a bombard. The lyrics evoke some Christian religious imagery, and make reference to Saint Sophia, but seem to criticize the idea of blindly clinging to faith while everything around you is falling apart.

“China” is a very short romantic ballad. Grebenshikov learned this song from a Russian singer named Alexander Vertinsky, who, according to my friend Irina, put the music for this song to a poem by a famous Russian poet named Nikolai Gumilev. After “China” comes “Three Sisters,” a song inspired by Tibetan mythology. The three sisters represent the goddesses of longevity. Grebenshikov evidently has a great interest in Tibetan spirituality, and his affinity for Buddhism permeates much of his music. This pensive song is given a more contemporary arrangement than the previous ones, with some orchestration and a subtle mandolin part in the chorus.

“Little Swallow” features an accordion backed up by more lively strumming. This has some of the most interesting lyrics on the album; I would guess that the swallow is a metaphor for the youth of Russia, and the song urges the swallows to disregard the warlike falcons around them — possibly representing the Soviet leadership — as they get ready to do battle. “My Lady (Gosudaryna)” also could be a metaphor for addressing the Soviet Union. The speaker in the song and Gosudaryna, his beloved, build a house that shines of silver on the outside but is empty inside. In the end, the house is treated with acid. The next song, “Fate’s Rusty Pail,” is a piano waltz with some orchestral accompaniment. The imagery in this song is arguably the most esoteric on the album. After this, Grebenshikov covers a famous Russian poet and guitarist named Bulat Okudjava with “Vanka Morozov.” This slightly dissonant minor-key song tells the story of a man who becomes hopelessly enamored of a girl in the circus. Following this is “The Fastest Plane on Earth,” a sad ballad sung from the perspective of a man who’s been separated from his love, and can’t return to her soon enough.

The next song, “Tarusa,” is based on a poem by Nikolai Zabolotski about a young girl who wants wings to fly away from her home town. “Dubrovsky,” which comes next, was inspired by a character from a novel by Pushkin. Like several other songs on the album, “Dubrovsky” incorporates stark religious imagery, in this case the New Jerusalem from the book of Revelation. Another song in waltz rhythm, “Dubrovsky” features an acoustic guitar accompanied by some light orchestration, but the uillean pipes at the very end distinguish this song musically from the others. After this comes the album’s longest song, “The Mares of Reckless Abandon.” This song features some excellent instrumental interplay involving a 12- string guitar, a mandolin, and some plucking on a violin. Again, the imagery includes some Christian religious symbols, but defies an easy explanation. In “Garçon Number 2,” Grebenshikov addresses a waiter present in a surreal dream. He seems to be talking about leaving the remains of an old life behind. The album finishes with “Russian Nirvana,” an anthemic expression of Grebenshikov’s devotion to Buddhism. I’d be curious to know if he’s ever made good on his lyrical vow to “take the lotus position in the middle of the Kremlin.”

After nearly thirty years of making music, the first half of which were spent in a very trying artistic climate, Boris Grebenshikov remains a highly revered, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in contemporary Russian music. While his lyrics often baffle even Russian listeners, he is generally considered the most poetic of Russia’s modern musical exports, and as he approaches his fiftieth birthday, he continues to perform for a devoted following in his homeland. Russian Songwriter contains fifteen songs which characterize Grebenshikov’s approach to making music. While I wouldn’t call any of the music groundbreaking, the songs all hold up quite well sonically. The lyrics will intrigue some while exasperating others — perhaps more so in translated form, perhaps not — but as even Nikolai Galkin conceded, “non-Russian speakers shouldn’t despair lyrics-wise and just enjoy the music.”

(Naxos World, 2002)

Boris Grebenshikov and Akvarium have a semi-official Web site. For an exhaustingly comprehensive fan site in English that’s devoted to all things Boris, try this. Of course, if you have any Russian friends, you can always just ask them. Chances are, they’ll know plenty.