The cover photograph shows a youthful Dylan holding an acoustic guitar and wearing his (then trademark) black corduroy cap. The album kicks off with a passable imitation of Jesse Fuller on “You’re No Good,” before getting into a Woody Guthrie vein for “Talkin’ New York.” It’s a fine song, but what follows is simply staggering.

The cover photograph shows a youthful Dylan holding an acoustic guitar and wearing his (then trademark) black corduroy cap. The album kicks off with a passable imitation of Jesse Fuller on “You’re No Good,” before getting into a Woody Guthrie vein for “Talkin’ New York.” It’s a fine song, but what follows is simply staggering.

“In my Time of Dying” is as authentic a piece of rural acoustic blues as you could possibly hope for from a 20-year old white boy. He’s got the pace exactly right, bottlenecking away on the guitar with a lipstick holder, and howling out the lyrics (“Jesus‚ gonna make up my dying bed”) like his life depends on it. By the time he sings “I am a Man of Constant Sorrow” you’re quite prepared to believe him (fresh-faced cover portrait notwithstanding). Elsewhere we get titles like “Fixin’ To Die Blues,” “Gospel Plow” and “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.” If that sounds like too much of a doom-fest, then fair enough, but it’s in the contradictory nature of the blues to be uplifting, and the young Dylan had learnt his lessons well.

“Song To Woody” is the best-known original on here (Dylan was to refer to Guthrie as “the greatest, Godliest man in the world). “House of the Rising Sun” was (with a few adjustments) turned into a hit single by The Animals a couple of years later, while Dylan himself revisited “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” many times in later performance, (including a spectacular rock workout in The Last Waltz movie.) “Pretty Peggy-o” and “Freight Train Blues” are good examples of the “Trad. arr. Dylan” effect. “Highway 51 Blues” provided Dylan with a driving blues song (and a good idea for a future song title.)

Bob Dylan is a compelling album that’s frequently overlooked. It’s the sound of a talented, restless young man absorbing influences like a sponge and channelling them back as fast as he could record. In many ways it’s comparable with The Elvis Presley Sun Collection in that both reveal precociously charismatic “outsiders” finding their formative solace and liberation in the blues.

It’s also notable for the quality of the performances — Dylan was probably practicing the guitar and harmonica with a greater diligence and hunger than at any subsequent time in his career! During the time between the recording and its eventual release however, the artist himself was already bored with the album and eager to follow it with a collection of his own songs. Nobody (outside of his Greenwich Village coterie) would have could have dared to predict what was coming next.

The year 1963 was when Britain went into “Beatlemania” with the release of the second album by the fab four. Paul McCartney pointed to the single “She Loves You” as an example of the increasing maturity of the Lennon-McCartney song writing partnership (a lyric in the third person)! Meanwhile, a relatively obscure American singer called Bob Dylan released his second album and John Lennon took to accessorising his collarless suits with a black corduroy cap.

The year 1963 was when Britain went into “Beatlemania” with the release of the second album by the fab four. Paul McCartney pointed to the single “She Loves You” as an example of the increasing maturity of the Lennon-McCartney song writing partnership (a lyric in the third person)! Meanwhile, a relatively obscure American singer called Bob Dylan released his second album and John Lennon took to accessorising his collarless suits with a black corduroy cap.

By this time Dylan had visited the (then flourishing) folk clubs of London, and had added a working knowledge of traditional British and Irish balladry to his already formidable musical vocabulary. The fruits of this can be heard to full effect on “Girl from the North Country” and “Bob Dylan’s Dream” (which earns a sleeve credit for Martin Carthy as the source of its tune). American traditions are well to the fore too, in the melodies of “Oxford Town” (a chilling account of racist murder), and “Masters of War” (a vitriolic response to the madness of the arms race).

“Bob Dylan’s Blues,” “Talking World War III Blues,” “Corrina, Corrina” and “Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance” provide both continuity and progression from the debut album. “Down the Highway,” is, as stated on the cover (or in the booklet for CD buyers) “a distillation of Dylan’s feelings about the blues,” while “I Shall be Free,” is funny, acerbic and head spinning — the “Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” in full, gloriously unpredictable flow.

There are three more songs on this album, and the titles alone have become classics, not to mention the songs themselves. “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” If all of this wasn’t enough, there’s still the iconic perfection of the album’s cover — Dylan strolling down a snowy New York street with the impossibly beautiful Suze Rotolo on his arm — to consider. Whether by chance or design, the message that comes through loud and clear is: “This is the coolest folk record that’s ever been.” Four decades later, it still is.

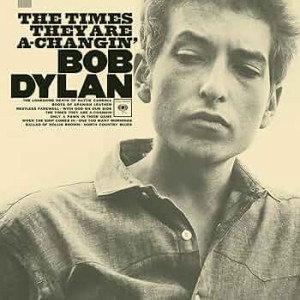

By 1964 the “buzzword” had changed from the ambiguous “folk” to the more specific “protest.” Once again, the album cover spells it out before the needle even hits the groove. The times were, indeed, “a-changin’‚” so it’s a forbiddingly monochrome, earnest Dylan that greets us here. The contrast with the colourful, romantic rambler of Freewheelin’ couldn’t be any starker.

By 1964 the “buzzword” had changed from the ambiguous “folk” to the more specific “protest.” Once again, the album cover spells it out before the needle even hits the groove. The times were, indeed, “a-changin’‚” so it’s a forbiddingly monochrome, earnest Dylan that greets us here. The contrast with the colourful, romantic rambler of Freewheelin’ couldn’t be any starker.

The title track is nothing less than a wake-up call to America. Writers are urged to “keep your eyes wide, the chance won’t come again,” politicians are warned that “there’s a battle outside, and it’s raging,” and parents are advised that “your sons and your daughters are beyond your command.” If Dylan was throwing his verses at the dartboard of public consciousness, then he got the first three straight into the bullseye.

“The Ballad of Hollis Brown,” “North Country Blues,” and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” are latter day American ballads of everyday injustice. “Hattie Carroll,” in particular, is a brilliantly sustained piece of storytelling that later formed the basis for C. Lester Franklin’s play “A Scaffold for Marionettes.”

“With God On Our Side,” and “Only A Pawn In Their Game,” find Dylan tackling the broader causes of violence. The former draws the listener’s attention to the absurdity of the notion of “holy” warfare, while the latter accuses the Southern political, religious and economic elites of encouraging and exploiting the racism of the white underclass. Come on over to Bob’s barbecue folks, the sacred cows are sizzling!

It’s not just the sins of the world that were weighing heavy on Dylan’s shoulders however, as his lover and muse Suze Rotolo had recently left both Dylan and the United States. The parting resulted in two songs here, “Boots Of Spanish Leather,” (an outstanding synthesis of traditional ballad and contemporary form) and “One Too Many Mornings” (stark, confessional heartbreak).

“When The Ship Comes In,” throws some brightness on proceedings with its brisk tempo and lyrical optimism. The song also provided the protest movement with an enduring rallying cry in the line, “the whole wide world is watching.” The album closer “Restless Farewell” is a personalised rewrite of the traditional “Parting Glass.”

With The Times They Are a-Changin’ Dylan made the definitive record of the folk-protest genre, and found himself lauded and courted by the old left and the new radicals alike. Joan Baez, (the “queen of the scene”) got busy with a little “courting” herself, and numerous Dylan imitators were sprouting guitars and harmonicas like teenage acne. While the politicos and protesters were gleefully rubbing their hands at the possibilities that this young, talented and hugely popular “mouthpiece” might afford them, it seems that nobody paid too much attention to the very last line of the album.”I’ll make my stand and remain as I am, and bid farewell and not give a damn.”

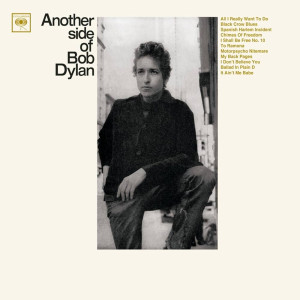

Dylan hated the title (suggested by producer Tom Wilson.) One can only speculate that someone at Columbia decided to go with it in an attempt to both celebrate its difference to The Times They Are a-Changin’ and placate the customers who expected more of the same (don’t worry folks, it’s just “another side” of what Bob does, he hasn’t changed really…)

Dylan hated the title (suggested by producer Tom Wilson.) One can only speculate that someone at Columbia decided to go with it in an attempt to both celebrate its difference to The Times They Are a-Changin’ and placate the customers who expected more of the same (don’t worry folks, it’s just “another side” of what Bob does, he hasn’t changed really…)

So, what exactly was this “other side,” then? It’s not as if Dylan had significantly changed the music by suddenly going electric or anything (that particular can of worms remained unopened at this point). It was the lyrics, that was what. The “spokesman of his generation” had the sudden temerity to write and record a bunch of love songs! From the resultant brouhaha, you’d be forgiven for expecting something like “A Hard Day’s Night” … not likely.

“All I Really Want to Do,” is described by Robert Shelton (in No Direction Home) as “a jape about a simple man trying to relate to a complex, defensive and Freudian-oriented woman.” I couldn’t put it any better than that, so I won’t. “Black Crow Blues,” is a fine, original example of Dylan’s continuing fascination with the music of the Delta, which features some effective down-home piano playing. “Spanish Harlem Incident,” is one of the love songs, but it’s a very different, more complex and grown up affair than anything being served up by his pop contemporaries of the time.

“Chimes of Freedom” is one of the all time great Dylan songs. A rolling, tidal melody sweeping in an articulate lyric bursting with compassion, imagery and metaphor. The “Dylan is a poet” brigade went into raptures and churned out essays comparing him with Blake and Rimbaud. While the intellectual debate got underway, Roger McGuinn simply recognised a hit when he heard one and quickly added this song (and a couple more from this album) to The Byrds’ repertoire. Dylan himself made light of his elevated status with the very next song, the talking blues “I Shall be Free No. 10,” where he declares “yippee! I’m a poet, and I know it, hope I don’t blow it!”

There’s more humour in the bawdy ballad “Motorpsycho Nitemare,” which tells the unlikely tale of a farmer’s daughter and a traveling salesman. In between these blasts of playfulness we get the haunting “To Ramona.” “My Back Pages,” is Dylan’s clearest statement of intent, and an open reply to those who felt betrayed by his straying from the path of political protest songs. Here Dylan speaks of becoming “my enemy, in the instant that I preach,” and observes: “good and bad, I define these terms, quite clear, no doubt, somehow. Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

“I Don’t Believe You” and “Ballad in Plain D” both deal with love gone wrong, the latter revealing the artist at his most painfully vulnerable, honest and candid. In truth it’s a quite harrowing narrative, detailing an incident when an argument between Dylan and Suze Rotolo’s sister got way out of hand. “I ran into the night, leaving all of love’s ashes behind me.” The closing song “It Ain’t Me, Babe” is another unsettling listen, as the singer adamantly refuses to be cast in the role of anyone’s hero. It’s often speculated that the song is addressed equally to Dylan’s critics and audience as to a lover. Either way, there’s a neat acknowledgement (and reversal) of an omnipresent catch phrase in the chorus. “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah,” sang the Beatles. “It ain’t me babe, no, no, no,” replied Dylan.

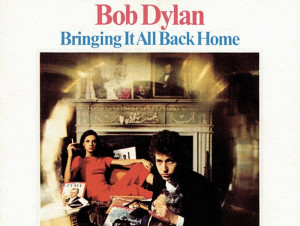

It’s late, I’m tired, and I’ve got a deadline to meet. The temptation is almost overwhelming to simply say that if you’ve never heard this album, just go and get a copy. Buy it, get it from your local library, borrow it from a friend, do anything, but just hear it. Because this, my dear and patient readers, is one of the finest records ever made, by anyone. That, of course, is just an opinion, not a review, so I guess that I’ll have to work a little harder! OK, here we go…

It’s late, I’m tired, and I’ve got a deadline to meet. The temptation is almost overwhelming to simply say that if you’ve never heard this album, just go and get a copy. Buy it, get it from your local library, borrow it from a friend, do anything, but just hear it. Because this, my dear and patient readers, is one of the finest records ever made, by anyone. That, of course, is just an opinion, not a review, so I guess that I’ll have to work a little harder! OK, here we go…

The album was originally conceived as having an electric side and an acoustic side. However, the advent of CD technology hasn’t diminished it in the slightest (it’s merely removed the necessity to get up and turn the record over half way through.)

“Subterranean Homesick Blues,” operates in the same musical territory as Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business” and manages to contain more memorable lines than most songwriters’ entire career output. If you want to understand what’s meant by “lyrical economy” or “the rhythm of language,” then look no further.

“She Belongs to Me” is a deceptively simple A-A-B blues structure song which swings easily through an account of Dylan’s often tempestuous relationship with Joan Baez. “Bow down to her on Sunday; salute her when her birthday comes.” The gentle, crooning vocal delivery almost disguises the sarcasm, but not quite.

“Maggie’s Farm” is a chugging rocker that satirises the futility of allowing oneself to be made into anyone’s puppet, servant or fool. It’s a protest song, but a universal, rather than specific one. “Love Minus Zero/No Limits” has all the hallmarks of a classic, faithful love song, but there’s a multiplicity of meanings and inferences simmering away beneath the gently bubbling melody: “The cloak and dagger dangles,” “The bridge at midnight trembles,” and “My love, she’s like some raven at my window with a broken wing.”

“Outlaw Blues” and “On the Road Again,” find Dylan stretching out in the exhilaration of performing with a rock group. This isn’t a performer in any mood to offer his critics apologies or explanations.”Don’t ask me nothin’ about nothin’‚” he snarls, “I just might tell you the truth.” “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” is a brilliantly sustained piece of American satire that rolls and tumbles across no less than eleven, thirteen-line verses without wasting a word or skipping a beat (if you don’t count the false start, which dissolves into laughter!)

And so, we come to the solo acoustic side and “Mr Tambourine Man.” If you’ve only heard the truncated Byrds version, then listen again. For all its familiarity, this song remains an enigmatic masterpiece, which (extraordinarily) appears to anticipate and articulate the emotional response of its listeners by its very performance. “I’m ready to go anywhere; I’m ready for to fade into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it.”

If, by now, you’ve fallen under Dylan’s “spell,” and you really are “ready to go anywhere,” then it’s an truly amazing journey from here on in, the first port of call being the “Gates of Eden.” This towering performance finds Dylan casting a weary across the tapestry of human experience before, finally, resigning himself to the realisation that “there are no truths outside the gates of Eden.” This song is nothing that could be called “easy listening,” but that doesn’t mean that you’ll want to skip it. The delivery demands your attention with every phrase.

Rather than go for a little light relief at this point, the mood, if anything, actually intensifies with “It’s Alright Ma, (I’m Only Bleeding.)” This is a truly colossal song, which Dylan navigates his way through with the help of a recycled Everly Brothers guitar riff and a torrent of the most quotable and acerbic lines ever set to music.

The closing song “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” is, appropriately, a song of farewell. At its most literal, it’s almost certainly about the end of the Dylan/Baez affair (they appear together in the cover photographs). This is certainly suggested in the lines “the vagabond who’s rapping at your door, is standing in the clothes that you once wore.” Joan, it should be remembered, was Dylan’s mentor and champion before she became his lover, introducing him to her audiences, singing his songs and using her position as the folk music “Queen,” to promote Dylan and all his works. By 1965 the young pretender had outgrown not only his advocate, but also the whole folk “scene,” and was rapidly ascending to the position of “King,” in a way to rival Elvis.

So, farewell to all that, and hello to rock superstar status, Highway 61, the “Wild, Thin, Mercury Sound,” the retreat to Woodstock and the Nashville Skyline. All of that can wait for another day. Five albums in three years (with another one to come before 1965 was through, when folks generally reckon that he really hit his stride…).

(Columbia Records, 1962)

(Columbia Records, 1963)

(Columbia Records, 1964)

(Columbia Records, 1964)

(Columbia Records, 1965)