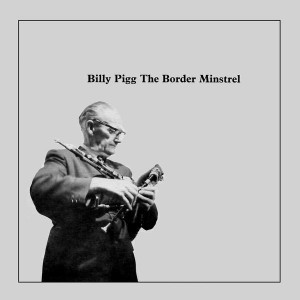

There were two things Janey Little loved best in the world: music and books, and not necessarily in that order. Her favorite musician was the late Billy Pigg, the Northumbrian piper from the northeast of England whose playing had inspired her to take up the small pipes herself as her principal instrument. — From the opening paragraph of Charles deLint’s The Little Country

There were two things Janey Little loved best in the world: music and books, and not necessarily in that order. Her favorite musician was the late Billy Pigg, the Northumbrian piper from the northeast of England whose playing had inspired her to take up the small pipes herself as her principal instrument. — From the opening paragraph of Charles deLint’s The Little Country

I’d never even seen a set of Northumbrian pipes until the 1980’s, ‘the lost decade.’ By then, the cleansing fires of punk rock had burnt themselves out, and all that seemed to be left in the ashes were the twin horrors of the New Romantics (posturing with synthesisers) and The New Wave of British Heavy Metal (posturing with guitars). Reasoning that there had to be something more fulfilling somewhere on the musical landscape of Thatcher’s Britain, I braved the uncharted waters of my local folk clubs and soon found myself among a few dozen other souls gathered in a cellar bar to hear a very young woman (barely out of school) by the name of Kathryn Tickell.

That encounter, my friends, can be viewed as a personal epiphany; the moment of realisation that traditional, instrumental music is capable of expressing joy, sorrow, passion and longing in a way that transcends the limitations of mere language. Like most shy teenagers, Tickell didn’t talk much during her performance, but was happy to chat during the interval about her instrument, her music and her influences. She talked about people called Forster Charlton and Tom Clough (two surnames associated more with soccer than music to ignorant blokes like me), Colin Ross, and, more than anyone else, Billy Pigg — a piper who died before she was even born. That name stuck in my memory because I thought if this girl who plays THAT music speaks so highly of him, then what in heaven’s name must Pigg sound like?

The answer (after that lengthy excursion along memory lane) is finally here, on this CD.

Originally released on vinyl LP back in 1971, ‘The Border Minstrel’ is a collection of live performances, some in concert, but mostly recorded at Pigg’s home. (Just to go back again to that Charles de Lint novel, the author cannily titled a fictitious favourite book belonging to Janey Little as The Lost Music, a phrase which could equally apply to these recordings).

Let’s just play it, and see what happens. After a short hum from the drones, Pigg’s chanter soars into life on ‘The High Level Hornpipe’ a tune composed by James Hill. There’s a brief moment of hesitation as the tune changes into ‘Biddleston Hornpipe,’ emphasising that this is not a carefully constructed studio set, but spontaneous musicianship, a case of the music playing the performer rather than the other way round. The second track is a concert performance featuring fluter John Doonan and fiddler Forster Charlton in what the stage compere calls ‘a great experiment.’ The ensuing juxtaposition of Irish and Northumbrian instrumentation and repertoire is the kind of thing that’s commonplace nowadays, but absolutely trailblazing for it’s time. Any researchers attempting to locate the starting point of what’s come to be known as Celtic Music can simply point to this CD and say: ‘there.’ Like the man says; ‘such a thing has never been before.’

Those Irish airs remind the listener that while Pigg is irrevocably associated with the relatively isolated, rural region of Northumberland, he was remarkably eclectic in his musical tastes and accomplishments. Scottish pipe tunes were particular favourites, as evidenced by his interpretations of ‘Skye Crofters’ and ‘Mallorca.’ Pigg also pioneered the practice of adjusting the pitch of the Northumbrian pipe drones to match the Highland variety; another example of being ahead of his time!

The majority of the tracks are completely solo performances, an aspect of traditional music that’s largely ignored in modern times in favour of group arrangement. That may suggest a somewhat ‘monochromatic’ listening experience, but in the case of these recordings it proves to be anything but. Freed from the constraints of strict tempo, Pigg utilises his virtuoso technique to subtly vary the tempo here, alter the rhythm there, and place unexpected emphasis on individual notes. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than on ‘The Wild Hills of Whannies,’ ostensibly a simple waltz-time melody, which Pigg transforms into a breathtaking, cinematic expression of place, emotion and personality. Hornpipes form a substantial proportion of the Northumbrian repertoire, and there are some outstanding examples here. In track seven ‘The Exhibition Hornpipe’ precedes ‘Billy Pigg’s Hornpipe’ which, in turn, changes time into a revelatory performance of ‘The Random Jig’ (perhaps most familiar as the tune which weaves through Fairport’s version of ‘The Widow of Westmoreland’s Daughter).

The copious booklet notes that accompany this release point out that before 1952, Pigg was primarily a farmer rather than a musician. He suffered a serious heart attack in that year from which he never recovered full health and it was this, rather than any desire for fame, that resulted in music being the primary occupation of his final years. In this respect, there’s an obvious similarity with the great blind Delta bluesmen or Ireland’s Turlough O’Carolan. While there’s an undoubted, unbounded joy about much of this music, there’s also, perhaps, an underlying sense of something more profound and elusive, something to do with life, mortality and the unquenchable human spirit.

As thoughts like these rise to the surface, it becomes little wonder that Charles de Lint chose this musician and these recordings as the embodiment of The Lost Music.

Rejoice with me, for what was lost is found.

(Leader Records, 2002)