Patrick O’Donnell wrote this review.

Patrick O’Donnell wrote this review.

Bill Miller has an amazing ability to tell a story, write music, sing a song, inspire a listener and express emotions. He can rock and rail about adversity in one breath, and in the next gently roll you into a soft cocoon of reassurance. He’s never preachy, never whiny, but you know with all certainty that this man is sincere, that he has felt the pain of loss and the sting of bigotry and is not afraid to tell you about it.

Miller, a Mohican-German raised on the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation in northern Wisconsin, makes music that is an uncanny combination of rock ‘n’ roll, folk and native, classical and contemporary. His sound seems influenced as much by Neil Young as it is by the traditional songs he sang as a child. No newcomer, Miller has recorded eight albums and contributed to many others, including the Pocahontas film soundtrack and releases from the likes of country greats Hal Ketchum and Michael Martin Murphey. He’s opened countless shows for Tori Amos and, at the other end of the spectrum, performed with Pearl Jam at an Apache Indian benefit in Arizona.

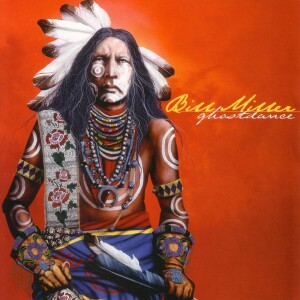

But his real strength can be found in his own releases, and Ghostdance is a powerhouse.

The CD is book-ended by versions of the hope-filled, “The Sun is Gonna Rise.” The first part, an instrumental prelude, swells into Miller’s powerful acoustic guitar as he strums the intro to “Every Mountain I Must Climb.” Part two closes the CD on a note of encouragement and promise, fading into Miller’s gentle reassurance that “The sun is gonna rise/the sun is gonna rise again.”

The construction — and strains of the tune — reminded me, strangely enough, of Neil Diamond’s soundtrack to the re-release of The Jazz Singer. The soundtrack opens to an orchestra slowly building into “America,” and Diamond belts out his call to the tired, the needy, the huddled masses. The album ends on a triumphant, orchestra-accompanied reprise of the same: a vision of hope for immigrants. In this case, though, the roles are reversed: Miller’s call is to the tired, needy, huddled masses who were here first, the masses who were kicked aside by immigrants. Yet the message is the same: hope.

And that’s really what Ghostdance is about: that, on this journey through the darkest night, there is light. And much of it shines from within. In the triumphant rocker “There is You,” Miller belts out, “You are a rock/you are a shield/you are a flower/in the field/you are a shelter in the storm.”

Not that Miller doesn’t throw in a good dose of jagged reality on the way. On “Every Mountain” he sings: “I saw Judas Iscariot/with a bottle of wine/talking suicide/with an old friend of mine/they gathered a crowd down at the end of the tracks/and a woman cried out/when is God comin’ back?” And in the second-to-last song, “Waiting for the Rain,” he sings of dashed dreams and broken promises: “two rings in an old pawn shop/two dusty winos cussin’ out a cop.”

It’s a rich musical experience, but not just because of his bright tremolo and poetic lyricism. Miller uses thoughtful arrangements that highlight his subject matter much like a photographer manipulates light to highlight a picture. The orchestral introduction and haunting, wailing flutes in the title track, his clear-as-a-bell acoustic guitar and the old Hammond B3 on “The Vision,” and his chants, shouts, howls and driving electric bass on “There is You,” all deftly illustrate Miller’s firm footing on the highest of singer-songwriter plateaus.

This year, the 45-year-old is a nominee in November’s Native American music awards, and Ghostdance seems a shoo-in for many categories. That may come as no surprise to his family. Miller’s Mohican name is Fush-Ya Heay Aka, or “Bird Song.” After listening to this album, it certainly seems a prophetic choice.

(Vanguard Records, 2000)