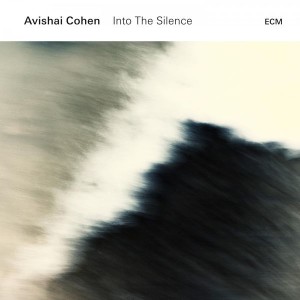

Israeli-born jazz trumpeter Avishai Cohen’s first ECM outing as a leader is this meditative album inspired by the death of his father in late 2014. This recording was one of those that slowly grew on me as I listened to it on repeat.

Israeli-born jazz trumpeter Avishai Cohen’s first ECM outing as a leader is this meditative album inspired by the death of his father in late 2014. This recording was one of those that slowly grew on me as I listened to it on repeat.

Seeing Cohen fronting a quartet in mid-2015 didn’t prepare me for the quiet impact of this quite different set of music. It did, however, prepare me to recognize the 30-something Cohen as a disciple of (among others) Miles Davis. So the opening section of the first track here, “Life and Death,” with its somber, Bill Evans-like chording from pianist Yonathan Avishai behind Cohen’s muted trumpet was more confirmation than revelation. It’s one of the more straightforward works on this date, with bassist Eric Revis and drummer Nasheet Waits sketching the minimal rhythm as Cohen and Avishai explore Cohen’s modal piece.

The entire recording has a fresh, exploratory feel. When the musicians got together in a French studio with ECM chief and producer Manfred Eicher to record, it was the first time this particular ensemble had played together, although most of the individuals had experience with one another in various combinations. With the exception of a run-through with pianist Avishai, it was also the first time any of them had heard these pieces Cohen had been living with for six months since his father’s passing.

It’s filled with small moments of the kind of magic that can happen with sympathetic musicians are exploring together. Pianist Yonathan Avishai’s Monk-like exploration of close, two-finger harmonies early in “Life And Death” is one. Another is the opening etude-like piano arpeggios on the 15-minute “Dream Like A Child.” It’s an homage to Cohen’s father’s unfulfilled dreams of playing music himself, a dream he made sure his three children (including clarinetist Anat and bassist Yuval) got to pursue. The title track, which adds tenor player Bill McHenry improvising with Cohen on long, pensive phrases, captures the loss and longing and sometimes turbulent emotions of the sudden absence of someone who has always been present. The mood swings from calm to agitation, the dynamics from hushed to urgent.

The steady forward motion of “Quiescence” and its less dark mood to me suggests the eventual acceptance of the way life continues in the midst of mourning. Both it and the closer, a solo-piano reprise of “Life And Death,” have an almost spring-like wistful feel to them.

Thanks especially to the rapport between Cohen and pianist Avishai, who have known each other since childhood, Into The Silence is a gem of a recording to revisit time and again.

ECM, 2016